Constitution of the Roman Republic

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Ancient Rome |

| Periods |

|

| Roman Constitution |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Titles and honours |

| Precedent and law |

|

|

| Assemblies |

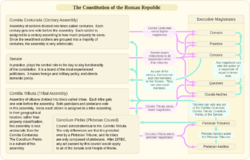

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles by which the Roman Republic was governed. The constitution evolved over time and was largely unwritten and uncodified, being passed down mainly through precedent.[1] Nevertheless, the constitution was also shaped by the body of written Roman law.[2]

Rather than creating a government that was primarily a democracy (as in ancient Athens), an aristocracy (as in ancient Sparta), or a monarchy (as in the Roman state before and, in many respects, after the Republic), the Roman Republic had a mixed constitution, with three separate branches of government:[3]

- The democratic element took the form of the legislative assemblies.

- The aristocratic element took the form of the Senate.

- The monarchical element took the form of the term-limited consuls.[4]

The ultimate source of sovereignty in this ancient republic, as in modern republics, was the people of Rome (Latin: populus Romanus).[5] The Roman people gathered into legislative assemblies to pass laws and to elect executive magistrates, such as consuls.[6] The Senate managed the day-to-day affairs in Rome, while magistrates presided over the courts.[7] Executive magistrates enforced the law and presided over the Senate and over the legislative assemblies.[8]

A complex set of checks and balances developed between these three branches, so as to minimize the risk of tyranny and corruption, and to maximize the likelihood of good government. However, the separation of powers between these three branches of government was not absolute; and moreover, a magistrate's term of office was often extended beyond one year, although this conflicted with the constitution.[9] A constitutional crisis began in 133 BC as a result of the struggles between the aristocracy and the common people.[10] Many years later this led to the collapse of the Roman Republic and its subversion into a much more autocratic form of government, the Roman Empire.[11]

Constitutional history (509–133 BC)

The republican constitution evolved gradually over time, largely shaped by the class struggle between the aristocratic patricians and the common people, the plebeians.[12] The main historical sources for the origins of the Roman political system, Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, relied heavily on the Roman annalists, who supplemented what little written history existed with oral history. This lack of evidence poses problems for the reliability of the traditional account of the republic's origins.[13]

According to this traditional account, Rome had been ruled by a succession of kings.[14] The Romans believed that this era, that of the Roman Kingdom, began in 753 BC and ended in 510 BC. After the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic, the people of Rome began electing two consuls each year.[15] According to the consular fasti, the first consuls were chosen in 509 BC.[16]

According to historian Andrew Lintott, some scholars doubt this traditional account. They argue that instead of being overthrown, the monarchy evolved into a government led by elected magistrates.[17] Remnants of the monarchy, however, were reflected in republican institutions, such as the office of rex sacrorum ("king of the sacred") and the interregnum (the period of time presided over by an interrex when the consulship or other magistracy was vacant).[18]

In 501 BC, the temporary office of dictator was first created to control popular unrest.[17] In the year 494 BC, the plebeians seceded to the Mons Sacer and demanded of the patricians the right to elect their own officials.[19][20] The patricians agreed, and the plebeians ended their secession. The plebeians called these new officials plebeian tribunes and gave these tribunes two assistants, called plebeian aediles.[21] In 449 BC, the Senate, in an effort to satisfy the plebeians, promulgated the Twelve Tables, the first and only codification of law during the republic.[22]

In 446 BC, quaestors were first elected, and the office of censor was created in 443 BC.[23][24] In 367 BC, plebeians were allowed to stand for the consulship, and this implicitly opened both the censorship as well as the dictatorship to plebeians.[25] In 366 BC, in an effort by the patricians to reassert their influence over the magisterial offices, two new offices were created. These two offices, the praetorship and the curule aedileship (so-called because its holder, like consuls and praetors, had the right to sit in a curule seat),[26] were at first open only to patricians, but within a generation they were open to plebeians as well.[21]

Beginning around the year 350 BC, the senators and the plebeian tribunes began to grow closer.[9] The Senate began giving tribunes more power, and the tribunes began to feel indebted to the Senate.[9] As the tribunes and the senators grew closer, plebeian senators began to routinely secure the office of tribune for members of their own families.[27] Also, this period saw the enacting of the Ovinian Law, which transferred the power to appoint new senators from the consuls to the censors. This law also required the censors to appoint any newly elected magistrate to the Senate,[28] which probably resulted in a significant increase in the number of plebeian senators.[29]

As the privileged status of the old patrician elite eroded over time, a plebeian aristocracy developed whose status was theoretically based on merit and popular election rather than birth.[29][30] Because patricians were ineligible to run for plebeian offices, the new plebeian aristocracy actually had more opportunities for advancement than their patrician counterparts.[31] Over time distinctions between patricians and plebeian aristocrats became less important, giving rise to a new "patricio-plebeian aristocracy" termed the nobilitas.[29]

In 287 BC, the plebeians seceded to the Janiculum hill. To end the secession, the Hortensian Law was passed to end the requirement that patrician senators consent before a bill could be brought before the Plebeian Council for a vote.[32] This was not the first law to require that an act of the Plebeian Council have the full force of law (over both plebeians and patricians),[33] since the Plebeian Council had acquired this power in 449 BC.[33] However, this new law robbed the patricians of their last major political power.[34]

The Hortensian Law resolved the last great political question of the earlier era; no important political changes occurred over the next 150 years (between 287 BC and 133 BC).[35] The electoral and legislative sovereignty of the assemblies was confirmed and would remain part of the constitution.[30] Nevertheless, the critical laws of this era were still enacted by the Senate due to the difficulty and inconvenience of organizing popular assemblies simply for the passage of ordinary legislation.[36] The Senate as an institution was stronger since it now represented noble plebeians as well as patricians.[30][34]

Senate

The Senate was the predominant political institution in the Roman Republic. The Senate's authority derived from custom and tradition.[37] The Senate's principal role was as an advisory council to the consuls on matters of foreign and military policy,[38] and it exercised a great deal of influence over consular decision-making. A decree from the Senate was called senatus consultum (plural senatus consulta). While this was formally "advice" from the Senate to a magistrate, the senatus consulta were usually obeyed by the magistrates.[39] If a senatus consultum conflicted with a law that was passed by a popular assembly, the law overrode the senatus consultum.[40]

The Senate also managed civil administration within the city. For example, only the Senate could authorize the appropriation of public money from the treasury,[38] unless a consul demanded it. In addition, the Senate would try individuals accused of political crimes (such as treason).[38] In addition, the Senate could invalidate laws passed by popular assemblies in violation of the proper procedures.[41]

Meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the pomerium), and were usually presided over by a consul.[42] Meetings were suffused in religious ritual. Temples were a preferred meeting site and auspices would be taken before the meeting could commence.[43]

The presiding consul began each meeting with a speech on an issue,[44] and then referred the issue to the senators, who discussed the matter by order of seniority.[45] Unimportant matters could be voted on by a voice vote or by a show of hands, while important votes resulted in a physical division of the house,[45] with senators voting by taking a place on either side of the chamber. Any vote was always between a proposal and its negative.[46]

Since all meetings had to end by nightfall,[39] a senator could talk a proposal to death (a filibuster) if he could keep the debate going until nightfall.[44] Any proposed motion could be vetoed by a tribune,[31] and if it was not vetoed, it was then turned into a final senatus consultum. Each senatus consultum was transcribed into a document by the presiding magistrate, and then deposited into the building that housed the treasury.[39]

Legislative assemblies

The right to make and repeal laws belonged to the Roman people voting in legislative meetings.[5] There were two types of formal legislative gatherings. The first, the comitia (or comitiatus), was an assembly of all Roman citizens convened to take a legal action, such as enacting laws, electing magistrates, and trying judicial cases.[47][48] The second type of legislative meeting was the council (Latin: concilium), which was a gathering of a specific group of citizens. For example, the Plebeian Council were meetings of the plebeians only.[49]

A third type of gathering, the convention (Latin: contio or conventio), was an unofficial forum for communication where citizens gathered to hear public announcements and arguments debated in speeches as well to witness the examination or execution of criminals. In contrast to the formal assembly or council, no legal decisions were made by the convention.[47] Voters met in conventions to deliberate prior to meeting in assemblies or councils to vote.[50]

Assemblies and councils operated according to established procedures overseen by the augurs. They could only be convened by magistrates, and citizens only voted on matters proposed by the presiding magistrate.[51] Roman citizens were organized into three types of voting units—curiae (familial groupings), centuries (for military purposes) and tribes (for civil purposes)—corresponding to three assemblies: the Curiate Assembly, the Centuriate Assembly, and the Tribal Assembly. Each unit (curia, century or tribe) cast one vote before the assembly.[52] The majority of individual votes in any century, tribe, or curia decided how that unit voted.

The Curiate Assembly served only a symbolic purpose in the late Republic. At some point, the 30 curiae ceased to actually meet and were instead represented by 30 lictors. It was this assembly that ratified the powers of newly elected magistrates by passing laws known as leges curiatae.[53]

The Centuriate Assembly was divided into 193 (later 373) centuries, with each century belonging to one of three classes: the officer class, the enlisted class, and the unarmed adjuncts.[54][55] Citizens were grouped into centuries according to the amount of property they owned, and wealthier centuries received more votes. During a vote, the centuries voted one at a time by class.[26] Only the Centuriate Assembly could elect consuls, praetors, and censors. Only it could declare war.[56] It was also the only institution that could ratify the results of a census.[57] This assembly rarely passed other kinds of legislation or heard capital trials.[58]

Tribal Assemblies were convened by consuls, praetors, or curule aediles.[26] The organization of the Tribal Assembly was much simpler than the Centuriate Assembly, since its organization was based on the thirty-five tribes. The tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical divisions (similar to modern electoral districts or constituencies).[59] Most legislation was enacted in the Tribal Assembly.[60] In addition, these assemblies elected quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes.[61]

The Plebeian Council was identical to the Tribal Assembly with one key exception: only plebeians had the power to vote before it. Members of the aristocratic patrician class were excluded from this assembly. In contrast, both classes were entitled to a vote in the Tribal Assembly. Under the presidency of a plebeian tribune, the Plebeian Council elected plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles, enacted laws called plebiscites, and presided over judicial cases involving plebeians.

Executive magistrates

Magistrates were elected officials of the Roman Republic. Each magistrate was vested with a degree of power.[62] The dictator (when there was one) had the highest level of power. After the dictator was the censor (when they existed), the consuls, the praetors, the curule aediles, and finally the quaestors. Each magistrate could only veto an action that was taken by an equally or lower ranked magistrate. Since plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were not magistrates of the republic,[63] they relied on the sacrosanctity of their person to obstruct unwanted actions.[64] When the tribune interposed his person to obstruct a political action it was known as intercessio. When the tribune interposed his person to aid an individual against a magistrate or another citizen, it was called auxilium.[65] Any resistance against the tribune was considered to be a capital offense.

The most significant constitutional power that a magistrate could hold was that of imperium or command, which was held only by consuls and praetors. This gave a magistrate the constitutional authority to issue commands (military or otherwise).

Election to a magisterial office resulted in automatic membership in the Senate (for life, unless impeached).[28] Once a magistrate's annual term in office expired, he had to wait ten years before serving in that office again. Occasionally a magistrate had his command powers extended through prorogation, which, in effect, allowed him to retain the powers of his office as a promagistrate.[66]

The consul was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate.[42][67] Two consuls were elected every year, and they had supreme power in both civil and military matters. Throughout the year, one consul was superior in rank to the other consul, and this ranking flipped every month between the two consuls.[68] Praetors administered civil law, presided over the courts, and commanded provincial armies.[69] The censors conducted the census, during which time they could appoint people to the Senate.[70] Aediles were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome and were vested with powers over the markets, public games and shows.[71] Quaestors usually assisted the consuls in Rome and the governors in the provinces with financial tasks.[71] The plebeian tribunes and the plebeian aediles were considered to be the representatives of the people. Thus, they acted as a popular check over the Senate through their veto powers and safeguarded the civil liberties of all Roman citizens.

In times of military emergency, a dictator was appointed for a term of six months.[72] Constitutional government dissolved, and the dictator became the absolute master of the state.[73] The dictator then appointed a magister equitum ("master of the horse") to serve as his most senior lieutenant.[74] Often the dictator resigned his office as soon as the matter that caused his appointment was resolved.[72] When the dictator's term ended, constitutional government was restored. The last ordinary dictator was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, extreme emergencies were addressed through the passage of the decree senatus consultum ultimum ("ultimate decree of the senate"). This suspended civil government, declared martial law,[75] and vested the consuls with dictatorial powers.

Constitutional instability (133–49 BC)

By the middle of the 2nd century BC, the economic position of the average plebeian had declined significantly.[76] The long military campaigns had forced citizens to leave their farms to fight, only to return to farms that had fallen into disrepair. The landed aristocracy began buying bankrupted farms at discounted prices, making it impossible for the average farmer to operate his farm at a profit.[76] Masses of unemployed plebeians soon began to flood into Rome, and thus into the ranks of the legislative assemblies, where their economic status usually led them to vote for the candidate who offered the most for them or who sponsored the most impressive games. A new culture of dependency was emerging, and hostility between the rich and the poor was growing.[77]

In 133 BC, Tiberius Gracchus was elected plebeian tribune and attempted to enact a law to distribute land to Rome's landless citizens.[64] Gracchus' law was vetoed by an aristocrat named Marcus Octavius. In an attempt to force Octavius to capitulate, Tiberius tried to turn the mob against Octavius by enacting a blanket veto over all governmental functions, which, in effect, shut down the entire city and precipitated rioting. While the land law was enacted, Tiberius was murdered when he stood for reelection to the tribunate. In 123 BC, Tiberius' brother Gaius was elected plebeian tribune. After passing a series of laws which were intended to weaken the Senate, Gaius Gracchus was murdered by agents of the aristocracy.[64] The people, however, had finally realized how weak the Senate had become.

In 88 BC, an aristocratic senator named Lucius Cornelius Sulla was elected consul and soon left for war in the east.[78] When a tribune revoked Sulla's command of the war, Sulla brought his army back to Italy, marched on Rome, secured the city, and left for the east again.[79] In 83 BC, he returned to Rome, and captured the city a second time.[80] In 82 BC, he made himself dictator, and then used his status as dictator to pass a series of constitutional reforms that were intended to strengthen the Senate.[81] In 80 BC, he resigned his dictatorship, and by 78 BC he was dead. While he thought that he had firmly established aristocratic rule, his own career had illustrated the fatal weakness in the constitution: that it was the army, not the Senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state.[82] In 70 BC, the generals Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus were both elected consul and quickly dismantled Sulla's constitution.[83]

In 62 BC, Pompey returned to Rome from battle in the east but found the Senate refusing to ratify the arrangements that he had made. Thus, when Julius Caesar returned from his governorship in Spain in 61 BC, he found it easy to make an arrangement with Pompey.[84] Caesar and Pompey, along with Crassus, established a private agreement, known as the First Triumvirate. Under the agreement, Pompey's arrangements were to be ratified, Crassus was to be promised a future consulship, and Caesar was to be promised a consulship in 59 BC and then the governorship of Gaul (modern France) immediately afterwards.[84] Caesar became consul in 59 BC, and, when his term as consul ended, he took command of four provinces. Eventually, the triumvirate was renewed, and Caesar's term as governor was extended for five years. In 54 BC, violence began sweeping the city.[85] The triumvirate ended in 53 BC when Crassus was killed in battle. In 50 BC, near the end of his term as governor, Caesar demanded the right to stand for election to the consulship in absentia. Without the protection afforded to him by the consulship or his army, he could be prosecuted for crimes he had committed. The Senate refused Caesar's demand, and in January 49 BC, the Senate resolved that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July of that year he would be considered an enemy of the republic.[86] In response, Caesar quickly crossed the Rubicon with his veteran army and marched towards Rome. Caesar's rapid advance forced Pompey, the consuls and the Senate to abandon Rome for Greece and allowed Caesar to enter the city unopposed.

Transition to empire (49–27 BC)

By 48 BC, after having defeated the last of his major enemies, Caesar tried to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed.[87] He increased his own authority and decreased the authority of Rome's other political institutions. Caesar held the office of dictator and alternated between the consulship and the proconsulship (in effect, a military governorship).[87] In 48 BC, Caesar was given the powers of a plebeian tribune,[88] which made his person sacrosanct, gave him the power to veto the Senate, and allowed him to dominate the legislative process. In 46 BC, Caesar was given the powers of censor,[88] which he used to fill the Senate with his own partisans. Caesar then raised the membership of the Senate from 600 to 900,[89] which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made it increasingly subservient to him.[90] Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the Parthian Empire. Since his absence from Rome would limit his ability to install his own consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates for the year 43 BC, and all consuls and plebeian tribunes for the year 42 BC;[89] so that the magistrates were appointees of the dictator rather than representatives of the people.[89]

After Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, Mark Antony formed an alliance with Caesar's adopted son and great-nephew, Gaius Octavian. Along with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, they formed an alliance known as the Second Triumvirate,[91] and held powers that were nearly identical to the powers that Caesar had held under his constitution. In effect, there was no constitutional difference between an individual who held the title of dictator and an individual who held the title of triumvir. While the conspirators who had assassinated Caesar were defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, the peace that resulted was only temporary. Antony and Octavian fought each other for the last time at Actium in 31 BC. Antony was defeated, and he committed suicide in 30 BC. In 29 BC, Octavian returned to Rome as the unchallenged master of the state. He enacted a series of constitutional reforms, the most important of which, in 27 BC, overthrew the republic. The reign of Octavian, whom history remembers as Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, marked the dividing line between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. By the time this process was complete: Rome had completed its transformation from a city-state with a network of dependencies into the capital of a world empire.[92]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Byrd, 161

- ↑ Lintott, 4

- ↑ Holland, 24

- ↑ Lintott, 17

- 1 2 Lintott, 3

- ↑ Lintott, 40

- ↑ Lintott, 65

- ↑ Byrd, 179

- 1 2 3 Abbott, 44

- ↑ Abbott, 96

- ↑ Abbott, 133

- ↑ Lintott, 16, 38

- ↑ Lintott, 27–28

- ↑ Holland, 1

- ↑ Holland, 2

- ↑ Lintott, 27

- 1 2 Lintott, 31

- ↑ Lintott, 28

- ↑ Abbott, 28

- ↑ Holland, 22

- 1 2 Holland, 5

- ↑ Lintott, 34

- ↑ Lintott, 35

- ↑ Abbott, 37

- ↑ Abbott, 42

- 1 2 3 Lintott, 53

- ↑ Abbott, 45

- 1 2 Abbott, 46

- 1 2 3 Abbott, 47

- 1 2 3 Lintott, 39

- 1 2 Holland, 26

- ↑ Abbott, 52

- 1 2 Abbott, 51

- 1 2 Abbott, 53

- ↑ Abbott, 63

- ↑ Abbott, 66

- ↑ Lintott, 66

- 1 2 3 Polybius, 133

- 1 2 3 Byrd, 44

- ↑ Polybius, 136

- ↑ Lintott, 62

- 1 2 Polybius, 132

- ↑ Lintott, 72

- 1 2 Lintott, 78

- 1 2 Byrd, 34

- ↑ Lintott, 83

- 1 2 Lintott, 42

- ↑ Abbott, 251

- ↑ Lintott, 43

- ↑ Taylor, 2

- ↑ Lintott, 40, 43

- ↑ Taylor, 40

- ↑ Lintott, 49

- ↑ Taylor, 85

- ↑ Cicero, 226

- ↑ Abbott, 257

- ↑ Taylor, 3, 4

- ↑ Lintott, 61

- ↑ Lintott, 51

- ↑ Lintott, 55

- ↑ Taylor, 7

- ↑ Abbott, 151

- ↑ Abbott, 196

- 1 2 3 Holland, 27

- ↑ Lintott, 33

- ↑ Lintott, 113

- ↑ Byrd, 20

- ↑ Cicero, 236

- ↑ Byrd, 32

- ↑ Lintott, 119

- 1 2 Byrd, 31

- 1 2 Byrd, 24

- ↑ Cicero, 237

- ↑ Byrd, 42

- ↑ Abbott, 240

- 1 2 Abbott, 77

- ↑ Abbott, 79–80. "A large number of freedmen and of those who had lost their holdings or their occupation in the country districts drifted to Rome and were admitted to the popular assemblies, in so far as their property allowed it. Their votes were in many cases to be had by the candidate who gave the most for them, or whose games were the most magnificent. The laws to punish bribery and to provide for a secret ballot, to which reference has already been made (p. 71), furnish an indication of the growing demoralization of the popular assemblies. The great inequality in wealth had another unfortunate political result. It gave rise to a spirit of dependence among the great mass of the people, in some cases of hostility toward the rich on the part of the poor, which found expression in class legislation of various kinds."

- ↑ Holland, 64

- ↑ Holland, 69

- ↑ Holland, 90

- ↑ Holland, 99

- ↑ Holland, 106

- ↑ Abbott, 109

- 1 2 Abbott, 112

- ↑ Abbott, 114

- ↑ Abbott, 115

- 1 2 Abbott, 134

- 1 2 Abbott, 135

- 1 2 3 Abbott, 137

- ↑ Abbott, 138

- ↑ Goldsworthy, 237

- ↑ Abbott, 129

References

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions (PDF). Elibron Classics. ISBN 0-543-92749-0.

- Byrd, Robert (1995). The Senate of the Roman Republic. U.S. Government Printing Office Senate Document 103-23.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1841). The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. vol. 1 (Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes By Francis Barham, Esq ed.). London: Edmund Spettigue.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2010). In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire. Orion Books, Ltd. ISBN 0-297-86401-7.

- Holland, Tom (2005). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. Random House Books. ISBN 1-4000-7897-0.

- Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926108-3.

- Polybius (1823). The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek. Vol 2 (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter.

- Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08125-X.

Further reading

- Ihne, Wilhelm (1853). Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution. William Pickering.

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone (1891). Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index. Scott, Foresman and Company.

- Mommsen, Theodor (1888). Roman Constitutional Law.

- Polybius. The Histories; Volumes 9–13. Cambridge Ancient History.

- Tighe, Ambrose (1886). The Development of the Roman Constitution. D. Apple & Co.

- Von Fritz, Kurt (1975). The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Primary sources

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius

- Secondary source material

- Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, by Montesquieu

- The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

- What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us