Cloud condensation nuclei

Cloud condensation nuclei or CCNs (also known as cloud seeds) are small particles typically 0.2 µm, or 1/100th the size of a cloud droplet [1] on which water vapour condenses. Water requires a non-gaseous surface to make the transition from a vapour to a liquid; this process is called condensation. In the atmosphere, this surface presents itself as tiny solid or liquid particles called CCNs. When no CCNs are present, water vapour can be supercooled at about -13°C (8°F) for 5-6 hours before droplets spontaneously form (this is the basis of the cloud chamber for detecting subatomic particles). In above freezing temperatures the air would have to be supersaturated to around 400% before the droplets could form.

The concept of cloud condensation nuclei is used in cloud seeding, that tries to encourage rainfall by seeding the air with condensation nuclei. It has further been suggested that creating such nuclei could be used for marine cloud brightening, a climate engineering technique.

Size, abundance, and composition

A typical raindrop is about 2 mm in diameter, a typical cloud droplet is on the order of 0.02 mm, and a typical cloud condensation nucleus (aerosol) is on the order of 0.0001 mm or 0.1 µm or greater in diameter. The number of cloud condensation nuclei in the air can be measured and ranges between around 100 to 1000 per cubic centimetre. The total mass of CCNs injected into the atmosphere has been estimated at 2x1012 kg over a year's time.

There are many different types of atmospheric particulates that can act as CCN. The particles may be composed of dust or clay, soot or black carbon from grassland or forest fires, sea salt from ocean wave spray, soot from factory smokestacks or internal combustion engines, sulfate from volcanic activity, phytoplankton or the oxidation of sulfur dioxide and secondary organic matter formed by the oxidation of volatile organic compounds. The ability of these different types of particles to form cloud droplets varies according to their size and also their exact composition, as the hygroscopic properties of these different constituents are very different. Sulfate and sea salt, for instance, readily absorb water whereas soot, organic carbon and mineral particles do not. This is made even more complicated by the fact that many of the chemical species may be mixed within the particles (in particular the sulfate and organic carbon). Additionally, while some particles (such as soot and minerals) do not make very good CCN, they do act as very good ice nuclei in colder parts of the atmosphere.

The number and type of CCNs can affect the lifetimes and radiative properties of clouds as well as the amount and hence have an influence on climate change;[2] details are not well understood but are the subject of research. There is also speculation that solar variation may affect cloud properties via CCNs, and hence affect climate.

Phytoplankton role

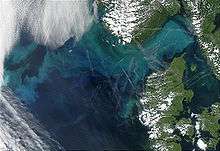

Sulfate aerosol (SO42− and methanesulfonic acid droplets) act as CCNs. These sulfate aerosols form partly from the dimethyl sulfide (DMS) produced by phytoplankton in the open ocean. Large algal blooms in ocean surface waters occur in a wide range of latitudes and contribute considerable DMS into the atmosphere to act as nuclei. The idea that an increase in global temperature would also increase phytoplankton activity and therefore CCN numbers was seen as a possible natural phenomenon that would counteract climate change. An increase of phytoplankton has been observed by scientists in certain areas but the causes are unclear.[3][4]

A counter-hypothesis is advanced in The Revenge of Gaia, the book by James Lovelock. Warming oceans are likely to become stratified, with most ocean nutrients trapped in the cold bottom layers while most of the light needed for photosynthesis in the warm top layer. Under this scenario, deprived of nutrients, marine phytoplankton would decline, as would sulfate cloud condensation nuclei, and the high albedo associated with low clouds. This is known as the CLAW hypothesis [5] (named after the authors' initials of a 1987 Nature paper) but no conclusive evidence to support this has yet been reported.

See also

References

- ↑ "Formation of Haze, Fog, and Clouds: Condensation Nuclei". Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.int-res.com/articles/meps2004/268/m268p031.pdf

- ↑ "Inter Research » MEPS » v157 » p39-52". Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ "- GAIA and CLAW". Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Charlson, Robert J.; Lovelock, James; Andreae, Meinrat O.; Warren, Stephen G. (1987). "Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate". Nature. 326 (6114): 655–661. Bibcode:1987Natur.326..655C. doi:10.1038/326655a0.

- N. H. Fletcher. The Physics of Rainclouds. (Cambridge University Press,1966).

External links

- www.agu.org

- www.grida.no

- Condensation Nucleus National Science Digital Library - Cloud Condensation Nucleus

- DMS and Climate