Computational fluid dynamics

| Computational physics |

|---|

|

|

Numerical analysis · Simulation |

|

Particle |

|

Scientists |

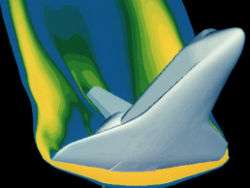

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and algorithms to solve and analyze problems that involve fluid flows. Computers are used to perform the calculations required to simulate the interaction of liquids and gases with surfaces defined by boundary conditions. With high-speed supercomputers, better solutions can be achieved. Ongoing research yields software that improves the accuracy and speed of complex simulation scenarios such as transonic or turbulent flows. Initial experimental validation of such software is performed using a wind tunnel with the final validation coming in full-scale testing, e.g. flight tests.

Background and history

The fundamental basis of almost all CFD problems are the Navier–Stokes equations, which define many single-phase (gas or liquid, but not both) fluid flows. These equations can be simplified by removing terms describing viscous actions to yield the Euler equations. Further simplification, by removing terms describing vorticity yields the full potential equations. Finally, for small perturbations in subsonic and supersonic flows (not transonic or hypersonic) these equations can be linearized to yield the linearized potential equations.

Historically, methods were first developed to solve the linearized potential equations. Two-dimensional (2D) methods, using conformal transformations of the flow about a cylinder to the flow about an airfoil were developed in the 1930s.[1]

One of the earliest type of calculations resembling modern CFD are those by Lewis Fry Richardson, in the sense that these calculations used finite differences and divided the physical space in cells. Although they failed dramatically, these calculations, together with Richardson's book "Weather prediction by numerical process",[2] set the basis for modern CFD and numerical meteorology. In fact, early CFD calculations during the 1940s using ENIAC used methods close to those in Richardson's 1922 book.[3]

The computer power available paced development of three-dimensional methods. Probably the first work using computers to model fluid flow, as governed by the Navier-Stokes equations, was performed at Los Alamos National Lab, in the T3 group.[4][5] This group was led by Francis H. Harlow, who is widely considered as one of the pioneers of CFD. From 1957 to late 1960s, this group developed a variety of numerical methods to simulate transient two-dimensional fluid flows, such as Particle-in-cell method (Harlow, 1957),[6] Fluid-in-cell method (Gentry, Martin and Daly, 1966),[7] Vorticity stream function method (Jake Fromm, 1963),[8] and Marker-and-cell method (Harlow and Welch, 1965).[9] Fromm's vorticity-stream-function method for 2D, transient, incompressible flow was the first treatment of strongly contorting incompressible flows in the world.

The first paper with three-dimensional model was published by John Hess and A.M.O. Smith of Douglas Aircraft in 1967.[10] This method discretized the surface of the geometry with panels, giving rise to this class of programs being called Panel Methods. Their method itself was simplified, in that it did not include lifting flows and hence was mainly applied to ship hulls and aircraft fuselages. The first lifting Panel Code (A230) was described in a paper written by Paul Rubbert and Gary Saaris of Boeing Aircraft in 1968.[11] In time, more advanced three-dimensional Panel Codes were developed at Boeing (PANAIR, A502),[12] Lockheed (Quadpan),[13] Douglas (HESS),[14] McDonnell Aircraft (MACAERO),[15] NASA (PMARC)[16] and Analytical Methods (WBAERO,[17] USAERO[18] and VSAERO[19][20]). Some (PANAIR, HESS and MACAERO) were higher order codes, using higher order distributions of surface singularities, while others (Quadpan, PMARC, USAERO and VSAERO) used single singularities on each surface panel. The advantage of the lower order codes was that they ran much faster on the computers of the time. Today, VSAERO has grown to be a multi-order code and is the most widely used program of this class. It has been used in the development of many submarines, surface ships, automobiles, helicopters, aircraft, and more recently wind turbines. Its sister code, USAERO is an unsteady panel method that has also been used for modeling such things as high speed trains and racing yachts. The NASA PMARC code from an early version of VSAERO and a derivative of PMARC, named CMARC,[21] is also commercially available.

In the two-dimensional realm, a number of Panel Codes have been developed for airfoil analysis and design. The codes typically have a boundary layer analysis included, so that viscous effects can be modeled. Professor Richard Eppler of the University of Stuttgart developed the PROFILE code, partly with NASA funding, which became available in the early 1980s.[22] This was soon followed by MIT Professor Mark Drela's XFOIL code.[23] Both PROFILE and XFOIL incorporate two-dimensional panel codes, with coupled boundary layer codes for airfoil analysis work. PROFILE uses a conformal transformation method for inverse airfoil design, while XFOIL has both a conformal transformation and an inverse panel method for airfoil design.

An intermediate step between Panel Codes and Full Potential codes were codes that used the Transonic Small Disturbance equations. In particular, the three-dimensional WIBCO code,[24] developed by Charlie Boppe of Grumman Aircraft in the early 1980s has seen heavy use.

Developers turned to Full Potential codes, as panel methods could not calculate the non-linear flow present at transonic speeds. The first description of a means of using the Full Potential equations was published by Earll Murman and Julian Cole of Boeing in 1970.[25] Frances Bauer, Paul Garabedian and David Korn of the Courant Institute at New York University (NYU) wrote a series of two-dimensional Full Potential airfoil codes that were widely used, the most important being named Program H.[26] A further growth of Program H was developed by Bob Melnik and his group at Grumman Aerospace as Grumfoil.[27] Antony Jameson, originally at Grumman Aircraft and the Courant Institute of NYU, worked with David Caughey to develop the important three-dimensional Full Potential code FLO22[28] in 1975. Many Full Potential codes emerged after this, culminating in Boeing's Tranair (A633) code,[29] which still sees heavy use.

The next step was the Euler equations, which promised to provide more accurate solutions of transonic flows. The methodology used by Jameson in his three-dimensional FLO57 code[30] (1981) was used by others to produce such programs as Lockheed's TEAM program[31] and IAI/Analytical Methods' MGAERO program.[32] MGAERO is unique in being a structured cartesian mesh code, while most other such codes use structured body-fitted grids (with the exception of NASA's highly successful CART3D code,[33] Lockheed's SPLITFLOW code[34] and Georgia Tech's NASCART-GT).[35] Antony Jameson also developed the three-dimensional AIRPLANE code[36] which made use of unstructured tetrahedral grids.

In the two-dimensional realm, Mark Drela and Michael Giles, then graduate students at MIT, developed the ISES Euler program[37] (actually a suite of programs) for airfoil design and analysis. This code first became available in 1986 and has been further developed to design, analyze and optimize single or multi-element airfoils, as the MSES program.[38] MSES sees wide use throughout the world. A derivative of MSES, for the design and analysis of airfoils in a cascade, is MISES,[39] developed by Harold "Guppy" Youngren while he was a graduate student at MIT.

The Navier–Stokes equations were the ultimate target of development. Two-dimensional codes, such as NASA Ames' ARC2D code first emerged. A number of three-dimensional codes were developed (ARC3D, OVERFLOW, CFL3D are three successful NASA contributions), leading to numerous commercial packages.

Methodology

In all of these approaches the same basic procedure is followed.

- During preprocessing

- The geometry (physical bounds) of the problem is defined.

- The volume occupied by the fluid is divided into discrete cells (the mesh). The mesh may be uniform or non-uniform.

- The physical modeling is defined – for example, the equations of motion + enthalpy + radiation + species conservation

- Boundary conditions are defined. This involves specifying the fluid behaviour and properties at the boundaries of the problem. For transient problems, the initial conditions are also defined.

- The simulation is started and the equations are solved iteratively as a steady-state or transient.

- Finally a postprocessor is used for the analysis and visualization of the resulting solution.

Discretization methods

The stability of the selected discretisation is generally established numerically rather than analytically as with simple linear problems. Special care must also be taken to ensure that the discretisation handles discontinuous solutions gracefully. The Euler equations and Navier–Stokes equations both admit shocks, and contact surfaces.

Some of the discretization methods being used are:

Finite volume method

The finite volume method (FVM) is a common approach used in CFD codes, as it has an advantage in memory usage and solution speed, especially for large problems, high Reynolds number turbulent flows, and source term dominated flows (like combustion).[40]

In the finite volume method, the governing partial differential equations (typically the Navier-Stokes equations, the mass and energy conservation equations, and the turbulence equations) are recast in a conservative form, and then solved over discrete control volumes. This discretization guarantees the conservation of fluxes through a particular control volume. The finite volume equation yields governing equations in the form,

where is the vector of conserved variables, is the vector of fluxes (see Euler equations or Navier–Stokes equations), is the volume of the control volume element, and is the surface area of the control volume element.

Finite element method

The finite element method (FEM) is used in structural analysis of solids, but is also applicable to fluids. However, the FEM formulation requires special care to ensure a conservative solution. The FEM formulation has been adapted for use with fluid dynamics governing equations. Although FEM must be carefully formulated to be conservative, it is much more stable than the finite volume approach.[41] However, FEM can require more memory and has slower solution times than the FVM.[42]

In this method, a weighted residual equation is formed:

where is the equation residual at an element vertex , is the conservation equation expressed on an element basis, is the weight factor, and is the volume of the element.

Finite difference method

The finite difference method (FDM) has historical importance and is simple to program. It is currently only used in few specialized codes, which handle complex geometry with high accuracy and efficiency by using embedded boundaries or overlapping grids (with the solution interpolated across each grid).

where is the vector of conserved variables, and , , and are the fluxes in the , , and directions respectively.

Spectral element method

Spectral element method is a finite element type method. It requires the mathematical problem (the partial differential equation) to be cast in a weak formulation. This is typically done by multiplying the differential equation by an arbitrary test function and integrating over the whole domain. Purely mathematically, the test functions are completely arbitrary - they belong to an infinite-dimensional function space. Clearly an infinite-dimensional function space cannot be represented on a discrete spectral element mesh; this is where the spectral element discretization begins. The most crucial thing is the choice of interpolating and testing functions. In a standard, low order FEM in 2D, for quadrilateral elements the most typical choice is the bilinear test or interpolating function of the form . In a spectral element method however, the interpolating and test functions are chosen to be polynomials of a very high order (typically e.g. of the 10th order in CFD applications). This guarantees the rapid convergence of the method. Furthermore, very efficient integration procedures must be used, since the number of integrations to be performed in a numerical codes is big. Thus, high order Gauss integration quadratures are employed, since they achieve the highest accuracy with the smallest number of computations to be carried out. At the time there are some academic CFD codes based on the spectral element method and some more are currently under development, since the new time-stepping schemes arise in the scientific world. You can refer to the C-CFD website to see movies of incompressible flows in channels simulated with a spectral element solver or to the Numerical Mechanics (see bottom of the page) website to see a movie of the lid-driven cavity flow obtained with a compeletely novel unconditionally stable time-stepping scheme combined with a spectral element solver.

Boundary element method

In the boundary element method, the boundary occupied by the fluid is divided into a surface mesh.

High-resolution discretization schemes

High-resolution schemes are used where shocks or discontinuities are present. Capturing sharp changes in the solution requires the use of second or higher-order numerical schemes that do not introduce spurious oscillations. This usually necessitates the application of flux limiters to ensure that the solution is total variation diminishing.

Turbulence models

In computational modeling of turbulent flows, one common objective is to obtain a model that can predict quantities of interest, such as fluid velocity, for use in engineering designs of the system being modeled. For turbulent flows, the range of length scales and complexity of phenomena involved in turbulence make most modeling approaches prohibitively expensive; the resolution required to resolve all scales involved in turbulence is beyond what is computationally possible. The primary approach in such cases is to create numerical models to approximate unresolved phenomena. This section lists some commonly used computational models for turbulent flows.

Turbulence models can be classified based on computational expense, which corresponds to the range of scales that are modeled versus resolved (the more turbulent scales that are resolved, the finer the resolution of the simulation, and therefore the higher the computational cost). If a majority or all of the turbulent scales are not modeled, the computational cost is very low, but the tradeoff comes in the form of decreased accuracy.

In addition to the wide range of length and time scales and the associated computational cost, the governing equations of fluid dynamics contain a non-linear convection term and a non-linear and non-local pressure gradient term. These nonlinear equations must be solved numerically with the appropriate boundary and initial conditions.

Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes

Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations are the oldest approach to turbulence modeling. An ensemble version of the governing equations is solved, which introduces new apparent stresses known as Reynolds stresses. This adds a second order tensor of unknowns for which various models can provide different levels of closure. It is a common misconception that the RANS equations do not apply to flows with a time-varying mean flow because these equations are 'time-averaged'. In fact, statistically unsteady (or non-stationary) flows can equally be treated. This is sometimes referred to as URANS. There is nothing inherent in Reynolds averaging to preclude this, but the turbulence models used to close the equations are valid only as long as the time over which these changes in the mean occur is large compared to the time scales of the turbulent motion containing most of the energy.

RANS models can be divided into two broad approaches:

- Boussinesq hypothesis

- This method involves using an algebraic equation for the Reynolds stresses which include determining the turbulent viscosity, and depending on the level of sophistication of the model, solving transport equations for determining the turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation. Models include k-ε (Launder and Spalding),[43] Mixing Length Model (Prandtl),[44] and Zero Equation Model (Cebeci and Smith).[44] The models available in this approach are often referred to by the number of transport equations associated with the method. For example, the Mixing Length model is a "Zero Equation" model because no transport equations are solved; the is a "Two Equation" model because two transport equations (one for and one for ) are solved.

- Reynolds stress model (RSM)

- This approach attempts to actually solve transport equations for the Reynolds stresses. This means introduction of several transport equations for all the Reynolds stresses and hence this approach is much more costly in CPU effort.

Large eddy simulation

Large eddy simulation (LES) is a technique in which the smallest scales of the flow are removed through a filtering operation, and their effect modeled using subgrid scale models. This allows the largest and most important scales of the turbulence to be resolved, while greatly reducing the computational cost incurred by the smallest scales. This method requires greater computational resources than RANS methods, but is far cheaper than DNS.

Detached eddy simulation

Detached eddy simulations (DES) is a modification of a RANS model in which the model switches to a subgrid scale formulation in regions fine enough for LES calculations. Regions near solid boundaries and where the turbulent length scale is less than the maximum grid dimension are assigned the RANS mode of solution. As the turbulent length scale exceeds the grid dimension, the regions are solved using the LES mode. Therefore, the grid resolution for DES is not as demanding as pure LES, thereby considerably cutting down the cost of the computation. Though DES was initially formulated for the Spalart-Allmaras model (Spalart et al., 1997), it can be implemented with other RANS models (Strelets, 2001), by appropriately modifying the length scale which is explicitly or implicitly involved in the RANS model. So while Spalart-Allmaras model based DES acts as LES with a wall model, DES based on other models (like two equation models) behave as a hybrid RANS-LES model. Grid generation is more complicated than for a simple RANS or LES case due to the RANS-LES switch. DES is a non-zonal approach and provides a single smooth velocity field across the RANS and the LES regions of the solutions.

Direct numerical simulation

Direct numerical simulation (DNS) resolves the entire range of turbulent length scales. This marginalizes the effect of models, but is extremely expensive. The computational cost is proportional to .[45] DNS is intractable for flows with complex geometries or flow configurations.

Coherent vortex simulation

The coherent vortex simulation approach decomposes the turbulent flow field into a coherent part, consisting of organized vortical motion, and the incoherent part, which is the random background flow.[46] This decomposition is done using wavelet filtering. The approach has much in common with LES, since it uses decomposition and resolves only the filtered portion, but different in that it does not use a linear, low-pass filter. Instead, the filtering operation is based on wavelets, and the filter can be adapted as the flow field evolves. Farge and Schneider tested the CVS method with two flow configurations and showed that the coherent portion of the flow exhibited the energy spectrum exhibited by the total flow, and corresponded to coherent structures (vortex tubes), while the incoherent parts of the flow composed homogeneous background noise, which exhibited no organized structures. Goldstein and Vasilyev[47] applied the FDV model to large eddy simulation, but did not assume that the wavelet filter completely eliminated all coherent motions from the subfilter scales. By employing both LES and CVS filtering, they showed that the SFS dissipation was dominated by the SFS flow field's coherent portion.

PDF methods

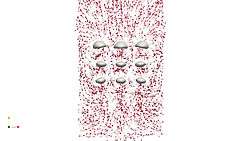

Probability density function (PDF) methods for turbulence, first introduced by Lundgren,[48] are based on tracking the one-point PDF of the velocity, , which gives the probability of the velocity at point being between and . This approach is analogous to the kinetic theory of gases, in which the macroscopic properties of a gas are described by a large number of particles. PDF methods are unique in that they can be applied in the framework of a number of different turbulence models; the main differences occur in the form of the PDF transport equation. For example, in the context of large eddy simulation, the PDF becomes the filtered PDF.[49] PDF methods can also be used to describe chemical reactions,[50][51] and are particularly useful for simulating chemically reacting flows because the chemical source term is closed and does not require a model. The PDF is commonly tracked by using Lagrangian particle methods; when combined with large eddy simulation, this leads to a Langevin equation for subfilter particle evolution.

Vortex method

The vortex method is a grid-free technique for the simulation of turbulent flows. It uses vortices as the computational elements, mimicking the physical structures in turbulence. Vortex methods were developed as a grid-free methodology that would not be limited by the fundamental smoothing effects associated with grid-based methods. To be practical, however, vortex methods require means for rapidly computing velocities from the vortex elements – in other words they require the solution to a particular form of the N-body problem (in which the motion of N objects is tied to their mutual influences). A breakthrough came in the late 1980s with the development of the fast multipole method (FMM), an algorithm by V. Rokhlin (Yale) and L. Greengard (Courant Institute). This breakthrough paved the way to practical computation of the velocities from the vortex elements and is the basis of successful algorithms. They are especially well-suited to simulating filamentary motion, such as wisps of smoke, in real-time simulations such as video games, because of the fine detail achieved using minimal computation.[52]

Software based on the vortex method offer a new means for solving tough fluid dynamics problems with minimal user intervention. All that is required is specification of problem geometry and setting of boundary and initial conditions. Among the significant advantages of this modern technology;

- It is practically grid-free, thus eliminating numerous iterations associated with RANS and LES.

- All problems are treated identically. No modeling or calibration inputs are required.

- Time-series simulations, which are crucial for correct analysis of acoustics, are possible.

- The small scale and large scale are accurately simulated at the same time.

Vorticity confinement method

The vorticity confinement (VC) method is an Eulerian technique used in the simulation of turbulent wakes. It uses a solitary-wave like approach to produce a stable solution with no numerical spreading. VC can capture the small-scale features to within as few as 2 grid cells. Within these features, a nonlinear difference equation is solved as opposed to the finite difference equation. VC is similar to shock capturing methods, where conservation laws are satisfied, so that the essential integral quantities are accurately computed.

Linear eddy model

The Linear eddy model is a technique used to simulate the convective mixing that takes place in turbulent flow.[53] Specifically, it provides a mathematical way to describe the interactions of a scalar variable within the vector flow field. It is primarily used in one-dimensional representations of turbulent flow, since it can be applied across a wide range of length scales and Reynolds numbers. This model is generally used as a building block for more complicated flow representations, as it provides high resolution predictions that hold across a large range of flow conditions.

Two-phase flow

The modeling of two-phase flow is still under development. Different methods have been proposed lately.[54][55] The Volume of fluid method has received a lot of attention lately, for problems that do not have dispersed particles, but the Level set method and front tracking are also valuable approaches . Most of these methods are either good in maintaining a sharp interface or at conserving mass . This is crucial since the evaluation of the density, viscosity and surface tension is based on the values averaged over the interface. Lagrangian multiphase models, which are used for dispersed media, are based on solving the Lagrangian equation of motion for the dispersed phase.

Solution algorithms

Discretization in the space produces a system of ordinary differential equations for unsteady problems and algebraic equations for steady problems. Implicit or semi-implicit methods are generally used to integrate the ordinary differential equations, producing a system of (usually) nonlinear algebraic equations. Applying a Newton or Picard iteration produces a system of linear equations which is nonsymmetric in the presence of advection and indefinite in the presence of incompressibility. Such systems, particularly in 3D, are frequently too large for direct solvers, so iterative methods are used, either stationary methods such as successive overrelaxation or Krylov subspace methods. Krylov methods such as GMRES, typically used with preconditioning, operate by minimizing the residual over successive subspaces generated by the preconditioned operator.

Multigrid has the advantage of asymptotically optimal performance on many problems. Traditional solvers and preconditioners are effective at reducing high-frequency components of the residual, but low-frequency components typically require many iterations to reduce. By operating on multiple scales, multigrid reduces all components of the residual by similar factors, leading to a mesh-independent number of iterations.

For indefinite systems, preconditioners such as incomplete LU factorization, additive Schwarz, and multigrid perform poorly or fail entirely, so the problem structure must be used for effective preconditioning.[56] Methods commonly used in CFD are the SIMPLE and Uzawa algorithms which exhibit mesh-dependent convergence rates, but recent advances based on block LU factorization combined with multigrid for the resulting definite systems have led to preconditioners that deliver mesh-independent convergence rates.[57]

Unsteady Aerodynamics

CFD made a major break through in late 70s with the introduction of LTRAN2, a 2-D code to model oscillating airfoils based on transonic small perturbation theory by Ballhaus and associates.[58] It uses a Murman-Cole switch algorithm for modeling the moving shock-waves.[59] Later it was extended to 3-D with use of a rotated difference scheme by AFWAL/Boeing that resulted in LTRAN3.[60][61]

Biomedical Engineering

CFD investigations are used to clarify the characteristics of aortic flow in detail that are otherwise invisible to experimental measurements. To analyze these conditions, CAD models of the human vascular system are extracted employing modern imaging techniques. A 3D model is reconstructed from this data and the fluid flow can be computed. Blood properties like Non-Newtonian behavior and realistic boundary conditions (e.g. systemic pressure) have to be taken into consideration. Therefore, making it possible to analyze and optimize the flow in the cardiovascular system for different applications.[62]

See also

- Advanced Simulation Library

- Blade element theory

- Central differencing scheme

- Computational magnetohydrodynamics

- Different types of boundary conditions in fluid dynamics

- Finite element analysis

- Finite volume method for unsteady flow

- Fluid simulation

- Immersed boundary method

- KIVA (software)

- Lattice Boltzmann methods

- List of finite element software packages

- Meshfree methods

- Moving particle semi-implicit method

- Multi-particle collision dynamics

- Multidisciplinary design optimization

- Numerical methods in fluid mechanics

- Smoothed-particle hydrodynamics

- Stochastic Eulerian Lagrangian method

- Turbulence modeling

- Visualization

- Wind tunnel

- Cavitation modelling

- Shape optimization

References

- ↑ Milne-Thomson, L.M. (1973). Theoretical Aerodynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-61980-X.

- ↑ Richardson, L. F.; Chapman, S. (1965). Weather prediction by numerical process. Dover Publications.

- ↑ Hunt (1998). "Lewis Fry Richardson and his contributions to mathematics, meteorology, and models of conflict". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 30. Bibcode:1998AnRFM..30D..13H. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.30.1.0.

- ↑ "The Legacy of Group T-3". Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ Harlow, F. H. (2004). "Fluid dynamics in Group T-3 Los Alamos National Laboratory:(LA-UR-03-3852)". Journal of Computational Physics. Elsevier. 195 (2): 414–433. Bibcode:2004JCoPh.195..414H. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2003.09.031.

- ↑ F.H. Harlow (1955). "A Machine Calculation Method for Hydrodynamic Problems". Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory report LAMS-1956.

- ↑ Gentry, R. A.; Martin, R. E.; Daly, J. B. (1966). "An Eulerian differencing method for unsteady compressible flow problems". Journal of Computational Physics. 1 (1): 87–118. Bibcode:1966JCoPh...1...87G. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(66)90014-3.

- ↑ Fromm, J. E.; F. H. Harlow (1963). "Numerical solution of the problem of vortex street development". Physics of Fluids. 6: 975. Bibcode:1963PhFl....6..975F. doi:10.1063/1.1706854.

- ↑ Harlow, F. H.; J. E. Welch (1965). "Numerical calculation of time-dependent viscous incompressible flow of fluid with a free surface" (PDF). Physics of Fluids. 8: 2182–2189. Bibcode:1965PhFl....8.2182H. doi:10.1063/1.1761178.

- ↑ Hess, J.L.; A.M.O. Smith (1967). "Calculation of Potential Flow About Arbitrary Bodies". Progress in Aerospace Sciences. 8: 1–138. Bibcode:1967PrAeS...8....1H. doi:10.1016/0376-0421(67)90003-6.

- ↑ Rubbert, Paul and Saaris, Gary, "Review and Evaluation of a Three-Dimensional Lifting Potential Flow Analysis Method for Arbitrary Configurations," AIAA paper 72-188, presented at the AIAA 10th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, San Diego California, January 1972.

- ↑ Carmichael, R. and Erickson, L.L., "PAN AIR - A Higher Order Panel Method for Predicting Subsonic or Supersonic Linear Potential Flows About Arbitrary Configurations," AIAA paper 81-1255, presented at the AIAA 14th Fluid and Plasma Dynamics Conference, Palo Alto California, June 1981.

- ↑ Youngren, H.H., Bouchard, E.E., Coopersmith, R.M. and Miranda, L.R., "Comparison of Panel Method Formulations and its Influence on the Development of QUADPAN, an Advanced Low Order Method," AIAA paper 83-1827, presented at the AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Danvers, Massachusetts, July 1983.

- ↑ Hess, J.L. and Friedman, D.M., "Analysis of Complex Inlet Configurations Using a Higher-Order Panel Method," AIAA paper 83-1828, presented at the AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Danvers, Massachusetts, July 1983.

- ↑ Bristow, D.R., "Development of Panel Methods for Subsonic Analysis and Design," NASA CR-3234, 1980.

- ↑ Ashby, Dale L.; Dudley, Michael R.; Iguchi, Steve K.; Browne, Lindsey and Katz, Joseph, “Potential Flow Theory and Operation Guide for the Panel Code PMARC”, NASA NASA-TM-102851 1991.

- ↑ Woodward, F.A., Dvorak, F.A. and Geller, E.W., "A Computer Program for Three-Dimensional Lifting Bodies in Subsonic Inviscid Flow," USAAMRDL Technical Report, TR 74-18, Ft. Eustis, Virginia, April 1974.

- ↑ Katz, J. and Maskew, B., "Unsteady Low-Speed Aerodynamic Model for Complete Aircraft Configurations," AIAA paper 86-2180, presented at the AIAA Atmospheric Flight Mechanics Conference, Williamsburg Virginia, August 1986.

- ↑ Maskew, Brian, "Prediction of Subsonic Aerodynamic Characteristics: A Case for Low-Order Panel Methods," AIAA paper 81-0252, presented at the AIAA 19th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, St. Louis, Missouri, January 1981.

- ↑ Maskew, Brian, “Program VSAERO Theory Document: A Computer Program for Calculating Nonlinear Aerodynamic Characteristics of Arbitrary Configurations”, NASA CR-4023, 1987.

- ↑ Pinella, David and Garrison, Peter, “Digital Wind Tunnel CMARC; Three-Dimensional Low-Order Panel Codes,” Aerologic, 2009.

- ↑ Eppler, R.; Somers, D. M., "A Computer Program for the Design and Analysis of Low-Speed Airfoils," NASA TM-80210, 1980.

- ↑ Drela, Mark, "XFOIL: An Analysis and Design System for Low Reynolds Number Airfoils," in Springer-Verlag Lecture Notes in Engineering, No. 54, 1989.

- ↑ Boppe, C.W., "Calculation of Transonic Wing Flows by Grid Embedding," AIAA paper 77-207, presented at the AIAA 15th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Los Angeles California, January 1977.

- ↑ Murman, Earll and Cole, Julian, "Calculation of Plane Steady Transonic Flow," AIAA paper 70-188, presented at the AIAA 8th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, New York New York, January 1970.

- ↑ Bauer, F., Garabedian, P., and Korn, D. G., "A Theory of Supercritical Wing Sections, with Computer Programs and Examples," Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems 66, Springer-Verlag, May 1972. ISBN 978-3540058076

- ↑ Mead, H. R.; Melnik, R. E., "GRUMFOIL: A computer code for the viscous transonic flow over airfoils," NASA CR-3806, 1985.

- ↑ Jameson A. and Caughey D., "A Finite Volume Method for Transonic Potential Flow Calculations," AIAA paper 77-635, presented at the Third AIAA Computational Fluid Dynamics Conference, Alburquerque New Mexico, June 1977.

- ↑ Samant, S.S., Bussoletti J.E., Johnson F.T., Burkhart, R.H., Everson, B.L., Melvin, R.G., Young, D.P., Erickson, L.L., Madson M.D. and Woo, A.C., "TRANAIR: A Computer Code for Transonic Analyses of Arbitrary Configurations," AIAA paper 87-0034, presented at the AIAA 25th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno Nevada, January 1987.

- ↑ Jameson, A., Schmidt, W. and Turkel, E., "Numerical Solution of the Euler Equations by Finite Volume Methods Using Runge-Kutta Time-Stepping Schemes," AIAA paper 81-1259, presented at the AIAA 14th Fluid and Plasma Dynamics Conference, Palo Alto California, 1981.

- ↑ Raj, P. and Brennan, J.E., "Improvements to an Euler Aerodynamic Method for Transonic Flow Simulation," AIAA paper 87-0040, presented at the 25th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno Nevada, January 1987.

- ↑ Tidd, D.M., Strash, D.J., Epstein, B., Luntz, A., Nachshon A. and Rubin T., "Application of an Efficient 3-D Multigrid Euler Method (MGAERO) to Complete Aircraft Configurations," AIAA paper 91-3236, presented at the AIAA 9th Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Baltimore Maryland, September 1991.

- ↑ Melton, J.E., Berger, M.J., Aftosmis, M.J. and Wong, M.D., "3D Application of a Cartesian Grid Euler Method," AIAA paper 95-0853, presented at the 33rd Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno Nevada, January 1995.

- ↑ Karmna, Steve L. Jr., "SPLITFLOW: A 3D Unstructurted Cartesian Prismatic Grid CFD Code for Complex Geometries," AIAA paper 95-0343, presented at the 33rd Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno Nevada, January 1995.

- ↑ Marshall, D., and Ruffin, S.M., " An Embedded Boundary Cartesian Grid Scheme for Viscous Flows using a New Viscous Wall Boundary Condition Treatment,” AIAA Paper 2004-0581, presented at the AIAA 42nd Aerospace Sciences Meeting, January 2004.

- ↑ Jameson, A., Baker, T.J. and Weatherill, N.P., "Calculation of Inviscid Tramonic Flow over a Complete Aircraft," AIAA paper 86-0103, presented at the AIAA 24th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno Nevada, January 1986.

- ↑ Giles, M., Drela, M. and Thompkins, W.T. Jr., "Newton Solution of Direct and Inverse Transonic Euler Equations," AIAA paper 85-1530, presented at the Third Symposium on Numerical and Physical Aspects of Aerodynamic Flows, Long Beach, California, January 1985.

- ↑ Drela, M. "Newton Solution of Coupled Viscous/Inviscid Multielement Airfoil Flows,", AIAA paper 90-1470, presented at the AIAA 21st Fluid Dynamics, Plasma Dynamics and Lasers Conference, Seattle Washington, June 1990.

- ↑ Drela, M. and Youngren H., "A User's Guide to MISES 2.53", MIT Computational Sciences Laboratory, December 1998.

- ↑ Patankar, Suhas V. (1980). Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid FLow. Hemisphere Publishing Corporation. ISBN 0891165223.

- ↑ Surana, K.A.; Allu, S.; Tenpas, P.W.; Reddy, J.N. (February 2007). "k-version of finite element method in gas dynamics: higher-order global differentiability numerical solutions". International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering. 69 (6): 1109–1157. Bibcode:2007IJNME..69.1109S. doi:10.1002/nme.1801.

- ↑ Huebner, K. H.; Thornton, E. A.; and Byron, T. D. (1995). The Finite Element Method for Engineers (Third ed.). Wiley Interscience.

- ↑ Launder, B. E.; D. B. Spalding (1974). "The Numerical Computation of Turbulent Flows". Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering. 3 (2): 269–289. Bibcode:1974CMAME...3..269L. doi:10.1016/0045-7825(74)90029-2.

- 1 2 Wilcox, David C. (2006). Turbulence Modeling for CFD (3 ed.). DCW Industries, Inc. ISBN 978-1-928729-08-2.

- ↑ Pope, S. B. (2000). Turbulent Flows. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59886-6.

- ↑ Farge, Marie; Schneider, Kai (2001). "Coherent Vortex Simulation (CVS), A Semi-Deterministic Turbulence Model Using Wavelets". Flow, Turbulence and Combustion. 66 (4): 393–426. doi:10.1023/A:1013512726409.

- ↑ Goldstein, Daniel; Vasilyev, Oleg (1995). "Stochastic coherent adaptive large eddy simulation method". Physics of Fluids A. 24 (7): 2497. Bibcode:2004PhFl...16.2497G. doi:10.1063/1.1736671.

- ↑ Lundgren, T.S. (1969). "Model equation for nonhomogeneous turbulence". Physics of Fluids A. 12 (3): 485–497. Bibcode:1969PhFl...12..485L. doi:10.1063/1.1692511.

- ↑ Colucci, P. J.; Jaberi, F. A; Givi, P.; Pope, S. B. (1998). "Filtered density function for large eddy simulation of turbulent reacting flows". Physics of Fluids A. 10 (2): 499–515. Bibcode:1998PhFl...10..499C. doi:10.1063/1.869537.

- ↑ Fox, Rodney (2003). Computational models for turbulent reacting flows. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65049-6.

- ↑ Pope, S. B. (1985). "PDF methods for turbulent reactive flows". Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 11 (2): 119–192. Bibcode:1985PrECS..11..119P. doi:10.1016/0360-1285(85)90002-4.

- ↑ Gourlay, Michael J. (July 2009). "Fluid Simulation for Video Games". Intel Software Network.

- ↑ Krueger, Steven K. (1993). "Linear Eddy Simulations Of Mixing In A Homogeneous Turbulent Flow". Physics Of Fluids. 5 (4): 1023. Bibcode:1993PhFl....5.1023M. doi:10.1063/1.858667.

- ↑ Hirt, C.W.; Nichols, B.D. (1981). "Volume of fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries". Journal of Computational Physics.

- ↑ Unverdi, S. O.; Tryggvason, G. (1992). "A Front-Tracking Method for Viscous, Incompressible, Multi-Fluid Flows". J. Comput. Phys.

- ↑ Benzi, Golub, Liesen (2005). "Numerical solution of saddle-point problems". Acta Numerica. 14: 1–137. Bibcode:2005AcNum..14....1B. doi:10.1017/S0962492904000212.

- ↑ Elman; Howle, V; Shadid, J; Shuttleworth, R; Tuminaro, R; et al. (January 2008). "A taxonomy and comparison of parallel block multi-level preconditioners for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations". Journal of Computational Physics. 227 (3): 1790–1808. Bibcode:2008JCoPh.227.1790E. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2007.09.026.

- ↑ Haigh, Thomas (2006). "Bioographies" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing.

- ↑ Murman, E.M. and Cole, J.D., "Calculation of Plane Steady Transonic Flows", AIAA Journal , Vol 9, No 1, pp 114-121, Jan 1971. Reprinted in AIAA Journal, Vol 41, No 7A, pp 301-308, July 2003

- ↑ Jameson, Antony (October 13, 2006). "Iterative solution of transonic flows over airfoils and wings, including flows at mach 1". 27 (3). Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics: 283–309. doi:10.1002/cpa.3160270302.

- ↑ Borland, C. J., “XTRAN3S - Transonic Steady and Unsteady Aerodynamics for Aeroelastic Applications,”AFWAL-TR-85-3214, Air Force Wright Aeronautical Laboratories, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH, January, 1986

- ↑ Kaufmann, T.A.S., Graefe, R., Hormes, M., Schmitz-Rode, T. and Steinseiferand, U., "Computational Fluid Dynamics in Biomedical Engineering", Computational Fluid Dynamics: Theory, Analysis and Applications , pp 109-136

Notes

- Anderson, John D. (1995). Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Basics With Applications. Science/Engineering/Math. McGraw-Hill Science. ISBN 0-07-001685-2

- Patankar, Suhas (1980). Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow. Hemisphere Series on Computational Methods in Mechanics and Thermal Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-89116-522-3

- Shah, Tasneem M.; Sadaf Siddiq; Zafar U. Koreshi. "An analysis and comparison of tube natural frequency modes with fluctuating force frequency from the thermal cross-flow fluid in 300 MWe PWR" (PDF). International Journal of Engineering and Technology. 9 (9): 201–205.

External links

- Course: Introduction to CFD – Dmitri Kuzmin (Dortmund University of Technology)

- Course: Numerical PDE Techniques for Scientists and Engineers, Open access Lectures and Codes for Numerical PDEs, including a modern view of Compressible CFD

- Fluid Simulation for Video Games, a series of over a dozen articles describing numerical methods for simulating fluids

_Mach_7_computational_fluid_dynamic_(CFD).jpg)