Compañía Transatlántica Española

.jpg)

Compañía Transatlántica Española (CTE), also known as Spanish Line in documents in English, is a passenger ocean line that has largely ceased operations although it still exists as a company. It is popularly known as "La Trasatlántica" in the Spanish language (Catalan: "La Transatlàntica").

History

The Compañía Transatlántica Española's first office in Spain was in Santander in the 19th century and its head office was transferred to Barcelona after Antonio López y López, the owner of the company, married Catalan lady, Dona Lluïsa Bru Lassús.

"La Trasatlántica" was established in colonial Cuba in 1850 as "Compañia de Vapores Correos A. López" by Spanish businessman Don Antonio López y López. It began operations with a 400-ton hybrid sailing ship-sidewheel steamer.

Antonio López was ennobled with the title of Marquis of Comillas in 1878. His company changed its name to "Compañía Transatlántica Española", its present name, after being registered as a joint stock company in 1881. Following the Marquis of Comillas's death in 1883, his fourth son, Don Claudio López Bru, took charge of the company. By 1894 the Compañía Transatlántica Española fleet reached 33 vessels with a total of 93.500 registered tonnes.[1]

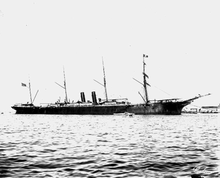

During the 1898 Spanish–American War, 21 CTE ocean liners were used by the Spanish Navy as auxiliary vessels in order to assist in the war effort. They tried to break the blockade that the United States were imposing on Cuba and the Philippines, the last great colonies of the Spanish crown, but were mostly unsuccessful.[2]

In 1920, after the difficult years of the First World War the Compañía Transatlántica embarked on a considerable expansion and modernization of its fleet. It worked together with the "Sociedad Estatal de Construcción Naval", a Spanish shipbuilding company, in this effort. CTE built well-equipped and luxurious ocean-going steamships that could compete with the best shipping companies of the planet. Claudio López Bru, second Marquis of Comillas, died in 1925.

Following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931, some of the Compañía Transatlántica's ocean liners underwent name changes for political reasons. Vessels named after Spanish royalty and aristocratic figures were re-christened; for example, steamer "Alfonso XIII", named after the newly ousted king, became ship "Habana", after Havana city in Cuba.

In 1939, as a result of the violence inflicted by both sides of the Spanish Civil War the Compañía Transatlántica saw a great part of its fleet destroyed or in bad state of disrepair. Some of the steamers belonging to the Compañía Transatlántica Española had been requisitioned by the Spanish Republican Navy and were used for evacuating refugees from coastal cities besieged by the Francoist armies.[3] Between 1950 and 1960 the shipping line was able to slowly recover but a storm was gathering which was to have almost lethal consequences for the company.

The arrival of the first passenger jets, like the Boeing 707, and the ensuing popularization of air travel, would deal a mortal blow to the transoceanic shipping lines throughout the world. Compañía Transatlántica shares crashed at the stock exchange and the ailing company was deprived of investors. In 1960, at one of the company's shareholder's meetings the idea was floated to transform CTE into an airline, but funds were not forthcoming. Between the mid-1960s and 1974, CTE liquidated practically all its fleet. One of the last luxury ocean-liners of the company was ship Virginia de Churruca, sold to Trasmediterránea which used it for ferry services to the Balearic Islands. The profits from sales like these, undertaken "at the point of death", were minimal.

In 1978 a non-functional Compañía Transatlántica Española, was integrated into the Instituto Nacional de Industria (INI), an entity of the Spanish state that absorbed failed companies in order to service debt, among other purposes.

In 1994 "La Transatlàntica" became a private company after being acquired by Naviera del Odiel. CTE managed to survive, but was only engaged minor shipping operations using leased ships, as well as in real-estate business. In its last days the Compañía Transatlántica was not even a shadow of the transoceanic shipping company it was in its days of glory, when its luxury passenger liners cruised the waters of the oceans around the world.

Following the strengthening of the Euro currency between 2005 y 2006, as well as higher fuel costs, Transatlántica found it increasingly difficult to service the debts to its creditors. Finally, in September 2012 it entered an insolvency procedure.[4]

Monuments

The Compañía Transatlántica Española pavilion at the 1888 Universal exhibition in Barcelona was located in its Maritime Section. It was one of the works of famous Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, better known for the Sagrada Familia. The CTE pavilion was demolished only a few years after its completion to make way for the Passeig Marítim, Barcelona's harbor promedade. Models of this now disappeared structure can be seen at the Sagrada Família museum.[5]

There is a sculptural relief representing a Compañía Transatlántica allegory on one side of the monument "A López y López" in Barcelona. This work was executed by Catalan sculptor Rossend Nobas.

See also

References

- ↑ Pictures and history of CTE ships

- ↑ List of CTE ships that took part as auxiliary vessels in the Spanish–American War

- ↑ Museo de Anclas - Ancla del "Alfonso XIII"

- ↑ 130 años después, la Trasatlántica entra en concurso

- ↑ Joan Bassegoda i Nonell, Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926), Barcelona, Fundació Caixa de Pensions, 1984. ISBN 84-505-0683-2. p. 236

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CTE. |

- Compañía Transatlántica Española - History

- Steamer Antonio López during the 1898 Spanish-American war

- Seizure of steamer Colón - Compañía Transatlántica Española

- CTE vessels (partial list)