Colossal Cave Adventure

| Colossal Cave Adventure | |

|---|---|

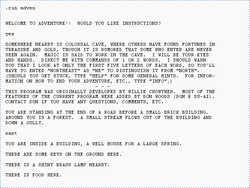

Crowther/Woods Adventure (1977) running on a PDP-10 | |

| Developer(s) | William Crowther and Don Woods |

| Platform(s) | initially DEC PDP-10 |

| Release date(s) | 1976 (Crowther); 1977 (Crowther/Woods) |

| Genre(s) | Adventure game |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

Colossal Cave Adventure (also known as ADVENT, Colossal Cave, or Adventure)[1] is a text adventure game, developed originally in 1976, by Will Crowther for the PDP-10 mainframe. The game was expanded upon in 1977, with help from Don Woods, and other programmers created variations on the game and ports to other systems in the following years.

In the game, the player controls a character through simple text commands to explore a cave rumored to be filled with wealth. Players earn predetermined points for acquiring treasure and escaping the cave alive, with the goal to earn the maximum amount of points offered. The concept bore out from Crowther's background as a caving enthusiast, with the game's cave structured loosely around the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky.[2]

Colossal Cave Adventure is the first known work of interactive fiction and, as the first text adventure game, is considered the precursor for the adventure game genre. Colossal Cave Adventure also contributed towards the role playing and roguelike genres.

Gameplay

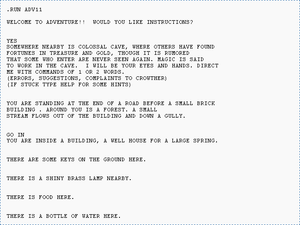

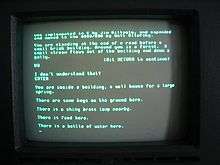

Adventure has the player's character explore a mysterious cave that is rumored to be filled with treasure and gold. To explore the cave, the player types in one- or two-word commands to move their character through the cave, interact with objects in the cave, pick up items to put into their inventory, and other actions. The program acts as a narrator, describing to the player what each location in the cave has, the results of certain actions, or if it did not understand the player's commands, asking for the player to retype their actions.

YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING. AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY. go south YOU ARE IN A VALLEY IN THE FOREST BESIDE A STREAM TUMBLING ALONG A ROCKY BED.

Program's replies are typically in a humorous, conversational tone, much as a dungeon master would use in leading players in a tabletop role-playing game.[3] A notable example is when the player dies after falling into a pit (player's commands in lower case, and the program's reply in all-capitals).

go west YOU FELL INTO A PIT AND BROKE EVERY BONE IN YOUR BODY! NOW YOU'VE REALLY DONE IT! I'M OUT OF ORANGE SMOKE! YOU DON'T EXPECT ME TO DO A DECENT REINCARNATION WITHOUT ANY ORANGE SMOKE, DO YOU? yes OKAY, IF YOU'RE SO SMART, DO IT YOURSELF! I'M LEAVING!

Certain actions may cause the death of the character (player has three lives), requiring the player to start again. The game has a point system, whereby completing certain goals earns a number of predetermined points. The ultimate goal is to earn the maximum amount of points (350 points), which partially correlates to finding all the treasures in the game and safely leaving the cave.

Development

Will Crowther was a programmer at Bolt, Beranek & Newman (BBN), and helped to develop the ARPANET (a forerunner of the Internet).[4] Crowther and his wife Pat were experienced cavers, having previously helped to create vector map surveys of the Mammoth Cave in Kentucky in the early 1970s for the Cave Research Foundation.[5] In addition, Crowther enjoyed playing the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons with a regular group which included Eric S. Roberts and Dave Lebling, one of the future founders of Infocom.[4] Following his divorce from Pat in 1975, Crowther wanted to connect better with his daughters, and decided a computerized simulation of his cave explorations with elements of his role-playing games would help.[5] He created a means by which the game could be controlled through natural language input so that it would be "a thing that gave you the illusion anyway that you'd typed in English commands and it did what you said".[6] Crowther later commented that this approach allowed the game to appeal to both non-programmers and programmers alike, as in the latter case, it gave programmers a challenge of how to make "an obstinate system" perform in a manner they wanted it to.[6]

Developed over 1975 and 1976, Crowther's original game consisted of about 700 lines of FORTRAN code,[7] with about another 700 lines of data, written for BBN's PDP-10 timesharing computer. The data included text for 78 map locations (66 actual rooms and 12 navigation messages), 193 vocabulary words, travel tables, and miscellaneous messages. On the PDP-10, the program loads and executes with all its game data in memory. It required about 60k words (nearly 300kB) of core memory, which was a significant amount for PDP-10/KA systems running with only 128k words. Crowther's original version did not include any scorekeeping.[8] Once the game was complete, Crowther showed it off to his co-workers at BBN for feedback, and then considered his work on the game complete, leaving the compiled game in a directory before taking a month off for vacation. During that time, others had found the game and it was distributed widely across the network, which had surprised Crowther on his return.[4] Though titled in-game as Colossal Cave Adventure, its executable file was simply named ADVENT, which led to this becoming an alternate name for the game.[4]

One of those that had discovered the game was Don Woods, a graduate student at Stanford University in 1976. Woods wanted to expand upon the game, and contacted Crowther to gain access to the source code. Woods added upon Crowther's code in FORTRAN to include more high fantasy-related elements based on his love of J.R.R. Tolkien. He also introduced a scoring system within the game, and added ten more treasures to collect in addition to the five in Crowther's original version.[9] His work expanded Crowther's game to approximately 3000 lines of code and 1800 lines of data. The data consisted of 140 map locations, 293 vocabulary words, 53 objects (15 treasure objects), travel tables, and miscellaneous messages. Like Crowther's original game, Woods' game also executed with all its data in memory, but required somewhat less core memory (42k words) than Crowther's game.[10][11] Don Woods continued releasing updated editions through to at least the mid-1990s.[9]

Crowther did not distribute the source code to his version, while Woods, once completed with his improvements, widely distributed the code alongside the compiled executable. Woods' 1977 version became the more recognizable and "canon" version of Colossal Cave Adventure in part due to wider code availability, on which nearly all revisions described in the following section were based.[8] Crowther's original code was thought to have been lost until 2007, when an unmodified version of it was found on Woods' student account archive.[4]

Later versions

Both Crowther's and Woods' version were designed to run on the PDP-10, enabling certain features unique to the platform. The PDP-10 architecture was 36-bit, with each word able to store five 7-bit ASCII characters. The game's FORTRAN code compared player's commands with its vocabulary, but using only the first five letters of each English word. Unfortunately, this limitation was silently evident to the game player too, and adversely affected gameplay ("north" would be equivalent to "northeast"). Hence, Woods added the five letter limit notes to Crowther's original game instructions. The PDP-10 also implemented application checkpointing which allows saving and restoring of the state of the entire program, instead of a more traditional save file. Both these features made it difficult to directly port the code to other architectures.

One of the first efforts to port the code was by Jim Gillogly of the RAND Corporation in 1977. Gillogly, with agreement from Crowther and Woods, spent several weeks porting the code to C to run on the more generic Unix architecture. It can be found as part of the BSD Operating Systems distributions, or as part of the "bsdgames" package under most Linux distributions, under the command name "adventure". The game was also ported to Prime Computer's super-mini running PRIMOS in the late 1970s, utilising FORTRAN IV, and to IBM mainframes running VM/CMS in late 1978, utilizing PL/I. In the late 1970s a freeware Commodore PET version was produced by Jim Butterfield; some years later this version was ported to the Commodore 64. Microsoft also released versions of Adventure in 1980 for the Apple II Plus and TRS-80 computers.

The Software Toolworks in 1981 released The Original Adventure. Endorsed by Crowther and Woods, it was the only version for which they received royalties.[12] Microsoft released Adventure in 1981 with its initial version of MS-DOS 1.0 as a launch title for the IBM PC, making it the first game available for the new computer.[13] It was released on a single-sided 5 1⁄4 inch disk, required 32K RAM, and booted directly from the disk; it could not be opened from DOS. Microsoft's Adventure contained 130 rooms, 15 treasures, 40 useful objects and 12 problems to be solved. The progress of two games could be saved on a diskette.[14] Later versions of the game moved away from general purpose programming languages such as C or Fortran, and were instead written for special interactive fiction engines, such as Infocom's Z-machine.

In addition to strict ports of the game, variations began to appear, typically denoted by the maximum number of points one could score in the game; the original version by Crowther and Woods had a maximum of 350 points. Russel Dalenberg's Adventure Family Tree page provides the best (though still incomplete) summary of different versions and their relationships.[15]

A generic version of the game was developed in 1981 by Graham Thomson for the ZX-81 as the Adventure-writing kit. This stripped-down version had space for 50 rooms and 15 objects and was designed to allow the aspiring coder to modify the game and thus personalize it. The game's code was published in April 1982.[16]

Dave Platt's influential 550-point version (released in 1984) was innovative in a number of ways. It broke away from coding the game directly in a programming language such as FORTRAN or C. Instead, Platt developed A-code – a language for adventure programming – and wrote his extended version in that language. The A-code source was pre-processed by a FORTRAN 77 (F77) "munger" program, which translated A-code into a text database and a tokenised pseudo-binary. These were then distributed together with a generic A-code F77 "executive", also written in F77, which effectively "ran" the tokenised pseudo-binary. Platt's version was also notable for providing a randomised variety of responses when informing the player that, for example, there was no exit in the nominated direction, introducing a number of rare "cameo" events, and committing some outrageous puns. Dave Platt's 550-point version of Colossal Cave – perhaps the most famous variant of this game other than the original, itself a jumping-off point for many other versions including Michael Goetz's 581 point CP/M version – included a long extension on the other side of the Volcano View. Eventually, the player descends into a maze of catacombs and a "fake Y2". If the player says "plugh" here the player is transported to a "Precarious Chair" suspended in midair above the molten lava. (The 581-point version was on SIGM011 from the CP/M Users Group, 1984.)

Critical analysis

Graham Nelson's Inform Designer's Manual presents "Advent" as the pioneer of the three-part structure typical of 1980s adventure games; he identifies the "prologue" with the aboveground region of the game "whose presence lends a much greater sense of claustrophobia and depth to the underground bulk of the game", the transition to the middle game as the "passage from the mundane to the fantastical", and the endgame or "Master Game".[17]

Dennis Jerz, among other cavers, has explored the Mammoth Cave system against Crowther's original layout for the game, and believe that much of Crowther's map and descriptions in the game matched well with the natural Colossal Cave as it had been in the 1970s at the time that Crowther would have surveyed it. Many of the rooms are named based on caving jargon used for marking survey points which Crowther would have used in his surveys.[5] In-game elements such as the small house at the start of the game and grates separating some rooms represented features that had been in place by the Park Service but since removed. Other natural elements such as a narrow cobble-strewn crawlway leading from the Bedquilt Cave to the Colossal Cave also matched consistency with the in-game locations.[18] Woods' expansion would add new features that were not part of the natural caves, as he had never visited the park.[18]

Influence

Colossal Cave Adventure is considered one of video gaming's most influential titles.[19] The game is generally the first known example of interactive fiction[lower-alpha 1] and established conventions that are standard in interactive fiction titles today, such as the use of shortened cardinal directions for commands like "e" for "east".[20] Colossal Cave Adventure directly inspired the creation of the adventure game genre. Games such as Adventureland by Scott Adams of Adventure International,[21] Zork by the team of Dave Lebling, Marc Blank, Tim Anderson, Bruce Daniels, and Albert Vezza of Infocom,[22] and Mystery House by Roberta and Ken Williams of Sierra Entertainment[23] were all directly influenced by Colossal Cave Adventure, and these companies would go on to become key innovators for the early adventure game genre.

As described by Matt Barton in Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games, Colossal Cave Adventure demonstrated the "creation of a virtual world and the means to explore it", and the inclusion of monsters and simplified combat.[24] For this, it is considered the precursor of role-playing games.[4] Glenn Wichman and Michael Toy state Adventure as an influence for their game Rogue in 1980, which would go on to become the namesake of the roguelike genre.[25]

Adventure also inspired the development of online multiplayer games like MUDs, the precursors of the modern-day MMORPG.[19][26] The Atari 2600 video game Adventure was an attempt to create a graphical version of Adventure,[27] and itself became the first known example of an action-adventure game, and introduced the fantasy genre to video game consoles.[28]

Memorable words and phrases

Due to its influence, a number of words and phrases used in Adventure have become recurring concepts in later games.

Xyzzy

"Xyzzy" is a magic word that teleports the player between two locations ("inside building" and the "debris room"). Entering the command from other locations produces the disappointing response "Nothing happens." As an in-joke tribute to Adventure, many later computer programs (not only games but also applications) include a hidden "xyzzy" command – the results of which range from the humorous to the straightforward.[29] Crowther stated that for its purpose in the game, "magic words should look queer, and yet somehow be pronounceable", leading him to select "xyzzy".[4] The meaning and origin of the term are unclear, but Crowther has said "I made it up out of whole cloth just for the game", and offered that as he had been considering working at Xerox at the time, he focused on a word starting with X.[4]

Maze of twisty little passages

In Crowther's original version of Adventure, he created a maze where each of ten room descriptions was exactly the same; YOU ARE IN A MAZE OF TWISTY LITTLE PASSAGES, ALL ALIKE.

The layout of this "all alike" maze was fixed, so the player would have to figure out how to map the maze. One method would be to drop objects in the rooms to act as landmarks, enabling one to map the section on paper.[8] Woods' version added a second maze, where the description of each of eleven rooms was similar but subtly different.

For example, YOU ARE IN A LITTLE MAZE OF TWISTING PASSAGES, ALL DIFFERENT. and YOU ARE IN A MAZE OF TWISTING LITTLE PASSAGES, ALL DIFFERENT. The layout was still fixed but the player did not have to drop inventory objects to map the maze. Instead, this "all different" maze required the player to recognize the wording changes to find maze exits and its solution. Don Woods was doing doctoral research in graph algorithms, and he designed this maze as (almost) a complete graph, with two exceptions important to gameplay.[4]

The phrase "you are in a maze of twisty little passages, all alike" has become memorialized and popularized in the hacker culture, where "passages" may be replaced with a different word, as the situation warrants. This phrase came to signify a situation when whatever action is taken does not change the result.[30] The line was used by Nick Montfort in the title for his book about the history of interactive fiction, Twisty Little Passages: An Approach To Interactive Fiction.[4][8]

Plugh

When the player arrives at a location known as "Y2", the player may (with 25% probability) receive the message "A hollow voice says 'PLUGH'." This magic word takes the player between the rooms "inside building" and "Y2". A popular theory is that the word is short for "plughole" (allegedly a caver term) but no evidence supports this claim, and the game does not feature a plughole in this location.

Some other games recognize "PLUGH" and will respond to it, usually by making a joke.[31] The adventure game Prisoner 2 contained a cavern with the word "PLUGH" written on the wall; if the player typed this word into the command parser, he was sent back to his starting point. The TRS-80 adventure game Haunted House – one of the few commercial adventure games playable with only 4K of RAM – requires the player to type PLUGH to enter the haunted house. If the player types PLUGH inside the haunted house, the game replies, "Sorry, only one PLUGH per customer." Another TRS-80 game, Bedlam, replies to PLUGH with "You got better."

Plugh.com[32] gives further historical background to the name, allegedly by Don Woods.

In popular culture

Though not mentioned by name, Colossal Cave Adventure is described in Tracy Kidder's 1981 non-fiction book The Soul of a New Machine, alluding to several of the location names from the game.[8]

The documentary Get Lamp on the history of text adventure games is named in part for the gaslight lamp that is one of the first objects the player encounters and must carry to solve Colossal Cave Adventure.[33]

Colossal Cave Adventure is a key plot point in episode 5 of the AMC TV series, Halt and Catch Fire, a period drama taking place in the early days of the personal computing revolution. The chief software designer uses the game as a competency test to determine which programmers will remain on the team. Those who hack the code and find the backdoors are retained.[34]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The 1968 program SHRDLU, in which the user uses natural language to instruct an artificial intelligence in moving objects around a virtual landscape, can be formally defined as interactive fiction, though typically is not considered to be such a title, as it was not designed as a narrative game.[8]

References

- ↑ Crowther, 1976; Crowther & Woods, 1977.

- ↑ Montfort 2005, pp. 85–87

- ↑ Dibbell 1998, pp. 56–57

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jerz, Dennis (2007). "Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther's Original "Adventure" in Code and in Kentucky". Digital Humanities Quarterly.

- 1 2 3 Rick Adams. "Here's where it all began...". The Colossal Cave Adventure page.

- 1 2 Montfort 2005, p. 91–92

- ↑ Crowther W., Crowther's original FORTRAN source code for Adventure, 1976

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Montfort, Nick (2003). Twisty Little Passages: An Approach To Interactive Fiction. Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13436-5.

- 1 2 Peterson, Dale (1983). Genesis II: Creation and Recreation with Computers. Reston Publishing Company. pp. 188–190. ISBN 0835924343.

- ↑ Crowther W., Woods D., PDP-10 FORTRAN source code advent-original.tar.gz, 1977

- ↑ Crowther W., Woods D., PDP-10 FORTRAN source code adv350-pdp10.tar.gz, 1977

- ↑ Bilofsky, Walt. "What year did I write my first computer program? (Hint: Vacuum tubes.)". Walt's Home Page. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Lemmons, Phil (October 1981). "The IBM Personal Computer / First Impressions". BYTE. p. 36. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: Product fact sheet". 03.ibm.com. 1981-08-12. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ Russel Dalenberg (March 20, 2004). "Adventure Family Tree" (ASCII Art). Retrieved March 10, 2016.]

- ↑ Thompson, Graham. Scot, Duncan, ed. Adventure. Your Computer. Vol.2, No.4. Pp.24-27. April 1982.

- ↑ Graham, Nelson (2001). The Inform Designer's Manual (PDF). Dan Sanderson. p. 375-382. ISBN 0-9713119-0-0.

- 1 2 Jerz, Dennis G. (2004-02-17). "Colossal Cave Adventure (c. 1975)". Dennis G. Jerz, Seton Hill University. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- 1 2 Staff (January 17, 2016). "The most important PC games of all time". PC Gamer. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ Sloane 2000, p. 57

- ↑ "Scott Adams Adventureland". Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ↑ Sloane 2000, p. 77

- ↑ Demaria & Wilson 2003, pp. 134–135

- ↑ Barton 2008, p. 28

- ↑ Craddock, David L (August 5, 2015). "Chapter 2: "Procedural Dungeons of Doom: Building Rogue, Part 1"". In Magrath, Andrew. Dungeon Hacks: How NetHack, Angband, and Other Roguelikes Changed the Course of Video Games. Press Start Press. ISBN 0-692-50186-X.

- ↑ Heron, Michael (August 3, 2016). "Hunt The Syntax, Part One". Gamasutra. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ↑ Connelly, Joey. "Of Dragons and Easter Eggs: A Chat With Warren Robinett". The Jaded Gamer. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ↑ Buchana, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN.

- ↑ Rick Adams. "Everything you ever wanted to know about ... the magic word XYZZY". The Colossal Cave Adventure page.

- ↑ Leiba, Barry (March 9, 2011). "You're In A Maze Of Twisty Little Passages, All Alike". Science 2.0. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ↑ David Welbourn. "plugh responses". A web page giving responses to "plugh" in many games of interactive fiction

- ↑ "plugh.com". plugh.com. 1997-02-27. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ Haff, Gordon (August 10, 2010). "'Get Lamp' illuminates the text adventure game". CNet. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ Bishop, Brian (June 30, 2014). "Close Up: 'Halt and Catch Fire' and the smallest TV in the world". The Verge. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

Bibliography

- Montfort, Nick (2005). Twisty Little Passages: An Approach To Interactive Fiction. Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13436-5.

- Barton, Matt (2008). Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games. CRC Press. ISBN 1439865248.

- Demaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-223172-4.

- Dibbell, Julian (1998). My Tiny Life: Crime and Passion in a Virtual World. Julian Dibbell. ISBN 0805036261.

- Sloane, Sarah (2000). Digital Fictions: Storytelling in a Material World. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-56750-482-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Colossal Cave Adventure |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Colossal Cave Adventure. |

- Colossal Cave Adventure Page

- Adventure at the Interactive Fiction Database with downloadable versions for many platforms.

- Adventure at the IFWiki. Includes download links for many versions and platforms.

- Jerz, Dennis G. (2007). "Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther's Original 'Adventure' in Code and in Kentucky". Digital Humanities Quarterly. The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- Crowther's original source code for Adventure (as recovered from Don Woods' student account at Stanford)

- Windows executable version of Crowther's original ADVENT

- iPod version of Colossal Cave Adventure

- Mac OS X version of Colossal Cave Adventure

- DEC PDP/8 OS/8 version of Colossal Cave Adventure

- Mike Arnautov's Adv770, an actively (as of 2015) maintained version of Adventure for Linux, Mac OS and Windows.

- IBM Archive: IBM Information Systems Division fact sheet distributed to the press on August 12, 1981.