Chuck Close

| Chuck Close | |

|---|---|

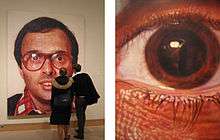

Mark (1978–1979), acrylic on canvas, left; detail of eye, right.[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Born |

Charles Thomas Close July 5, 1940 Monroe, Washington |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | B.A., University of Washington, 1962; M.F.A., Yale University |

| Known for | Photorealistic painter, photographer |

| Spouse(s) | Leslie Rose |

Charles Thomas "Chuck" Close (born July 5, 1940) is an American painter/artist and photographer who achieved fame as a photorealist, through his massive-scale portraits. Close often paints abstract portraits, which hang in collections internationally. Although a catastrophic spinal artery collapse in 1988 left him severely paralyzed, he has continued to paint and produce work that remains sought after by museums and collectors. Close also creates photo portraits using a very large format camera.

Early life and education

Chuck Close was born in Monroe, Washington.[1] His father, Leslie Durward Close, died when he was eleven years old. His mother's name was Mildred Wagner Close.[2] Close suffered, as a child, from a neuromuscular condition that made it difficult to lift his feet and a bout with nephritis that kept him out of school for most of sixth grade. Even when in school, he did poorly, as result of dyslexia, which wasn't diagnosed at the time.[3]

Most of his early works are very large portraits based on photographs (Photorealism or Hyperrealism technique) of family and friends, often other artists. Chuck suffers from prosopagnosia (face blindness) and has suggested that this condition is what first inspired him to do portraits.[4] In an interview with Phong Bui in The Brooklyn Rail, Close describes an early encounter with a Jackson Pollock painting at the Seattle Art Museum: "I went to the Seattle Art Museum with my mother for the first time when I was 14.[5] I saw this Jackson Pollock drip painting with aluminum paint, tar, gravel and all that stuff. I was absolutely outraged, disturbed. It was so far removed from what I thought art was. However, within 2 or 3 days, I was dripping paint all over my old paintings. In a way I've been chasing that experience ever since."[6]

Close attended Everett Community College in 1958–60.[7] Notable Snohomish County resident, author John Patric, was an early intellectual influence on Chuck Close.[8] In 1962, Close received his B.A. from the University of Washington in Seattle. In 1961 he won a coveted scholarship to the Yale Summer School of Music and Art,[7] and the following year entered the graduate degree program at Yale University, where he received his MFA in 1964. Among Close's classmates at Yale were Brice Marden, Vija Celmins, Janet Fish, Richard Serra, Nancy Graves, Jennifer Bartlett, Robert Mangold, and Sylvia Plimack Mangold.[9] After Yale, he studied at Academy of Fine Arts Vienna for a while on a Fulbright grant.[10] When he returned to the US, he worked as an art teacher at the University of Massachusetts. Close came to New York City in 1967 and established himself in SoHo.[9]

Work

Style

Throughout his career, Chuck Close has expanded his contribution to portraiture through the mastery of such varied drawing and painting techniques as ink, graphite, pastel, watercolor, conté crayon, finger painting, and stamp-pad ink on paper; printmaking techniques, such as Mezzotint, etching, woodcuts, linocuts, and silkscreens; as well as handmade paper collage, Polaroid photographs, Daguerreotypes, and Jacquard tapestries.[11] His early airbrush techniques inspired the development of the ink jet printer.[12]

Close had been known for his skillful brushwork as a graduate student at Yale University. There, he emulated Willem de Kooning and seemed "destined to become a third-generation abstract expressionist, although with a dash of Pop iconoclasm".[9] After a period in which he experimented with figurative constructions, Close began a series of paintings derived from black-and-white photographs of a female nude, which he copied onto canvas and painted in color.[13] As he explained in a 2009 interview with the Cleveland Ohio Plain Dealer, he made a choice in 1967 to make art hard for himself and force a personal artistic breakthrough by abandoning the paintbrush. "I threw away my tools", Close said. "I chose to do things I had no facility with. The choice not to do something is in a funny way more positive than the choice to do something. If you impose a limit to not do something you've done before, it will push you to where you've never gone before."[14] One photo of Philip Glass was included in his resulting black-and-white series in 1969, redone with watercolors in 1977, again redone with stamp pad and fingerprints in 1978, and also done as gray handmade paper in 1982.

Working from a gridded photograph, he builds his images by applying one careful stroke after another in multi-colors or grayscale. He works methodically, starting his loose but regular grid from the left hand corner of the canvas.[15] His works are generally larger than life and highly focused.[16] "One demonstration of the way photography became assimilated into the art world is the success of photorealist painting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is also called super-realism or hyper-realism and painters like Richard Estes, Denis Peterson, Audrey Flack, and Chuck Close often worked from photographic stills to create paintings that appeared to be photographs. The everyday nature of the subject matter of the paintings likewise worked to secure the painting as a realist object."[17]

Close suffers from prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness, in which he is unable to recognize faces. By painting portraits, he is better able to recognize and remember faces.[18] On the subject, Close has said, "I was not conscious of making a decision to paint portraits because I have difficulty recognizing faces. That occurred to me twenty years after the fact when I looked at why I was still painting portraits, why that still had urgency for me. I began to realize that it has sustained me for so long because I have difficulty in recognizing faces."[19]

Although his later paintings differ in method from his earlier canvases, the preliminary process remains the same. To create his grid work copies of photos, Close puts a grid on the photo and on the canvas and copies cell by cell. Typically, each square within the grid is filled with roughly executed regions of color (usually consisting of painted rings on a contrasting background) which give the cell a perceived 'average' hue which makes sense from a distance. His first tools for this included an airbrush, rags, razor blade, and an eraser mounted on a power drill. His first picture with this method was Big Self Portrait, a black and white enlargement of his face to a 107.5 by 83.5 inches (273 cm × 212 cm) canvas, made in over four months in 1968, and acquired by the Walker Art Center in 1969. He made seven more black and white portraits during this period. He has been quoted as saying that he used such diluted paint in the airbrush that all eight of the paintings were made with a single tube of mars black acrylic.

Later work has branched into non-rectangular grids, topographic map style regions of similar colors, CMYK color grid work, and using larger grids to make the cell by cell nature of his work obvious even in small reproductions. The Big Self Portrait is so finely done that even a full page reproduction in an art book is still indistinguishable from a regular photograph.

"The Event"

On December 7, 1988, Close felt a strange pain in his chest. That day he was at a ceremony honoring local artists in New York City and was waiting to be called to the podium to present an award. Close delivered his speech and then made his way across the street to Beth Israel Medical Center where he suffered a seizure which left him paralyzed from the neck down. The cause was diagnosed as a spinal artery collapse.[20] He had also suffered from neuromuscular problems as a child.[21] Close called that day "The Event". For months, Close was in rehab strengthening his muscles with physical therapy; he soon had slight movement in his arms and could walk, yet only for a few steps. He has relied on a wheelchair ever since. Close spoke candidly about the effect disability had on his life and work in the book Chronicles of Courage: Very Special Artists written by Jean Kennedy Smith and George Plimpton and published by Random House.[22]

However, Close continued to paint with a brush strapped onto his wrist with tape, creating large portraits in low-resolution grid squares created by an assistant. Viewed from afar, these squares appear as a single, unified image which attempt photo-reality, albeit in pixelated form. Although the paralysis restricted his ability to paint as meticulously as before, Close had, in a sense, placed artificial restrictions upon his hyperrealist approach well before the injury. That is, he adopted materials and techniques that did not lend themselves well to achieving a photorealistic effect. Small bits of irregular paper or inked fingerprints were used as media to achieve astoundingly realistic and interesting results. Close proved able to create his desired effects even with the most difficult of materials to control. Close has made a practice, over recent years, of representing artists who are similarly invested in portraiture, like Cecily Brown, Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker, and Zhang Huan.[23]

Prints

Close has been a printmaker throughout his career, with most of his prints published by Pace Editions, New York.[7] He made his first serious foray into print making in 1972, when he moved himself and family to San Francisco to work on a mezzotint at Crown Point Press for a three-month residency. To accommodate him, Crown Point found the largest copper plate it could (36 inches wide) and purchased a new press, allowing Close to make a work that was 3 feet by 4 feet. In 1986 he went to Kyoto to work with Tadashi Toda, a highly respected woodblock printer.[24]

In 1995, curator Colin Westerbeck used a grant from the Lannan Foundation to bring Close together with Grant Romer, director of conservation at the George Eastman House.[12] Ever since, the artist has also continued to explore difficult photographic processes such as daguerreotype in collaboration with Jerry Spagnoli and sophisticated modular/cell-based forms such as tapestry. Close's photogravure portrait of artist Robert Rauschenberg, "Robert" (1998), appeared in a 2009 exhibition at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York, featuring prints from Universal Limited Art Editions.[25] In the daguerreotype photographs, the background defines the limit of the image plane as well as the outline of the subject, with the inky pitch-black setting off the light, reflective quality of the subject's face.[26]

In a 2014 interview with Terrie Sultan, Close said: "I've had two great collaborators in the God knows how many years I've been making prints. One was the late Joe Wilfer, who was called the 'prince of pulp' … and now I'm working with Don Farnsworth in Oakland at…Magnolia Editions: I do the watercolor prints with him, I do the tapestries with him. These are the most important collaborations of my life as an artist."[27]

Since 2012, Magnolia Editions has published an ongoing series of archival watercolor prints by Close which use the artist's grid format and the precision afforded by contemporary digital printers to layer water-based pigment on Hahnemuhle rag paper[28] such that the native behavior of watercolor is manifested in each print: "The edges of each pixel bleed with cyan, magenta, and yellow, creating a kind of three-dimensional fog effect behind the intended color swatches."[29] The watercolor prints are created using more than 10,000 of Close's hand-painted marks which were scanned into a computer and then digitally rearranged and layered by the artist using his signature grid.[30] These works have been called Close's first major foray into digital imagery:[31] according to Close, "It's amazing how precise a computer can be working with light and color and water."[32] A New York Times review notes that the "exaggerated breakdown of the image, particularly when viewed at close range," that characterizes Close's work "is also apparent in... [watercolor print] portraits of the artists Cecily Brown, Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker and Zhang Huan."[33]

Tapestries

Close's wall-size tapestry portraits, in which each image is composed of thousands of combinations of woven colored thread, depict subjects including Kate Moss, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, Lucas Samaras, Philip Glass, Lou Reed, Roy Lichtenstein, and Close himself.[33] They are produced in collaboration with Donald Farnsworth.[34] Although many are translated from black-and-white daguerreotypes, all of the tapestries use multiple colors of thread. No printing is involved in their creation; colors and values appear to the viewer based on combinations of more than 17,800 colored warp (vertical) and weft (horizontal) threads, in an echo of Close's typical grid format.[35][36] Close's tapestry series began with a 2003 black-and-white portrait of Philip Glass. In August 2013 he debuted two color self-portraits at Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York.[28] Reviewing this exhibition, Marion Weiss writes: "Close's Jacquard tapestries are not obviously fragmented, but are created by repeating multicolor warp and weft threads that are optically blended. Thus, portraits of Lou Reed and Roy Lichtenstein, for example, seem 'whole.' It's only when we get closer that we see the individual threads, which are woven together."[37]

Commissions

In 2010, Close was commissioned to create twelve large mosaics, totaling more than 2,000 square feet (190 m2), for the under-construction 86th Street subway station on the Second Avenue Subway in Manhattan.[38][39]

Vanity Fair's 20th Annual Hollywood edition in March 2014 featured a portfolio of 20 Polaroid portraits of movie stars shot by Close, including Robert De Niro, Scarlett Johansson, Helen Mirren, Julia Roberts and Oprah Winfrey. Close requested that his subjects be ready to be photographed without makeup or hair-styling and used a large-format 20x24" Polaroid camera for the close-ups.[40]

A fragment of Close's portrait of singer-songwriter Paul Simon was used as the cover art for his 2016 album Stranger to Stranger. The right eye appears on the cover; the entire portrait is in the liner notes.

Exhibitions

Close's first solo exhibition, held in 1967 at the University of Massachusetts Art Gallery, Amherst, featured paintings, painted reliefs, and drawings based on photographs of record covers and magazine illustrations. The exhibition captured the attention of the university administration which promptly closed it, citing the male nudity as obscene. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) came to the defense of Close and a landmark court case ensued. A Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice decided in favor of the artist against the university. When the university appealed Close chose not to return to Boston, and ultimately the decision was overturned by an appeals court.[41] (Close was later awarded an Honorary Doctorate of the Arts by the University of Massachusetts in 1995.)[41]

Close credits the Walker Art Center and its then-director Martin Friedman for launching his career with the purchase of Big Self-Portrait (1967–1968)[42] in 1969, the first painting he sold[43] His first one-man show in New York was in 1970 at Bykert Gallery. His first print was the focus of a "Projects" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1972. In 1979 his work was included in the Whitney Biennial and the following year his portraits were the subject of an exhibition at the Walker Art Center. His work has since been the subject of more than 150 solo exhibitions including a number of major museum retrospectives.[10] After Close abruptly canceled a major show of his work scheduled for 1997 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[44] the Museum of Modern Art announced that it would present a major midcareer retrospective of the artist's work in 1998 (curated by Kirk Varnedoe and later traveling to the Hayward Gallery, London, and other galleries in 1999).[45][46] In 2003 the Blaffer Gallery at the University of Houston presented a survey of his prints, which travelled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the following year.[10] His most recent retrospective – "Chuck Close Paintings: 1968 / 2006", at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2007 – travelled to the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen, Germany, and the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. He has also participated in almost 800 group exhibitions,[47] including documentas V (1972) and VI (1977), the Venice Biennale (1993, 1995, 2003), and the Carnegie International (1995).[26]

In 2013, Close's work was featured in an exhibit in White Cube Bermondsey, London. "Process and Collaboration" displayed not only a number of finished prints and paintings but included plates, woodblocks, and mylar stencils which were used to produce a number of prints.[48]

In December 2014 his work was exhibited in Australia at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, which he visited.[49]

Collections

Close's work is in the collections of most of the great international museums of contemporary art, including the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Tate Modern in London, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis who published Chuck Close: Self-Portraits 1967–2005 coauthored with curators Siri Engberg and Madeleine Grynsztejn.[7][50]

Recognition

The recipient of the National Medal of Arts from President Clinton in 2000,[51] the New York State Governor's Art Award, and the Skowhegan Arts Medal, among many others, Close has received over 20 honorary degrees including one from Yale University, his alma mater.[47] In 1990, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate Academician, and became a full Academician in 1992. New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg appointed the artist to the Cultural Affairs Advisory Commission, a body mandated by the City Charter to advise the mayor and the cultural affairs commissioner.[52] Close painted President Bill Clinton in 2006 and photographed President Barack Obama in 2012.[41] In 2010 he was appointed by Obama to the President's Committee on the Arts and Humanities.[10]

In 2005, composer Philip Glass wrote a musical portrait of Close. The composition, a 15-minute piece for solo piano, was the idea of Bruce Levingston, a concert pianist, who commissioned it through the Premiere Commission and who performed the piece at a recital at Alice Tully Hall that year.[53]

Art market

Close has been represented by The Pace Gallery (in New York City) since 1977, and by White Cube (in London) since 1999.[54] Already in 1999, Close's Cindy II (1988), a portrait of the photographer Cindy Sherman sold for $1.2 million, against a high estimate of $800,000.[55] In 2005, John (1971–72) was sold at Sotheby's to the Broad Art Foundation for $4.8 million.[56]

Personal life

Close lives and works in Bridgehampton, New York and Long Beach, NY (both on the south shore of Long Island)[9] and New York City's East Village.[57] He has two daughters with Leslie Rose;.[58][59] they divorced in 2011.

Fundraising and community service

In 2007 Close was honored by the New York Stem Cell Foundation and donated artwork for an exclusive online auction.[60]

In September 2012 Magnolia Editions published two tapestry editions and three print editions by Close depicting President Barack Obama. The first tapestry was unveiled at the Mint Museum in North Carolina in honor of the Democratic National Convention. These tapestries and prints were sold as a fundraiser to support the Obama Victory Fund. A number of the works were signed by both Close and Obama. Close has previously sold work at auction to raise funds for the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Al Gore.[61][62]

In October 2013, Close donated a watercolor print of Genevieve Bahrenburg and a watercolor print self-portrait to ARTWALK NY, a cause that benefits the Coalition for the Homeless.[63] In the same year work by Close was also sold to benefit the Lunchbox Fund.[64]

Close was one of eight artists who volunteered in 2013 to participate in President Barack Obama's Turnaround Arts initiative, which aims to improve low-performing schools by increasing student "engagement" through the arts. Close mentored 34 students in the sixth through eighth grades at Roosevelt School in Bridgeport, Connecticut, one of eight schools in the nation to participate in this public-private partnership developed in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Education and the White House Domestic Policy Council. Close was honored by mayor Bill Finch with a key to the city at the November 7 reception at the Housatonic Community College Museum of Art, where five of Close's watercolor prints were exhibited alongside artwork by students participating in the program.[65]

In the media

In 1998, PBS broadcast documentary filmmaker Marion Cajori's Emmy-nominated short, "Chuck Close: A Portrait in Progress."[66] In 2007, Cajori made "Chuck Close", a full-length expansion of the first film.[67] British art critic Christopher Finch wrote a biography, Chuck Close: Life, which was published in 2010, a sequel of sorts to Finch's 2007 book, Chuck Close: Work, a career-spanning monograph.[68]

Close appeared on The Colbert Report on August 12, 2010, where he admitted he watches the show every night.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mark (1978–1979), acrylic on canvas, seen on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, left. Detail of eye, right. Mark, a painting that took fourteen months to complete, was constructed from a series of airbrushed layers that imitated CMYK color printing. Compare the picture's integrity close up with the later work below, executed through a different technique.

References

- ↑ "Chuck Close". Art in the Allen Center. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ↑ "Oral history interview with Chuck Close, 1987 May 14-Sept. 30". Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ↑ Hylton, Wil S. (13 July 2016). "The Mysterious Metamorphosis of Chuck Close". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ http://www.mosaicartnow.com/2010/07/prosopagnosia-portraitist-chuck-close/

- ↑ http://www.biography.com/people/chuck-close-9251491#early-life

- ↑ Bui, Phong (June 2008). "In Conversation: Chuck Close with Phong Bui". The Brooklyn Rail.

- 1 2 3 4 Chuck Close Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

- ↑ "Chuck Close: Life".

- 1 2 3 4 Helen A. Harrison (February 22, 2004), Following the Light, and Making Faces New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 Chuck Close Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- ↑ Chuck Close, October 29 – December 22, 2011 Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

- 1 2 Lyle Rexer (March 12, 2000), Chuck Close Rediscovers the Art in an Old Method New York Times.

- ↑ Chuck Close Tate Modern, London.

- ↑ Norman, M. Contemporary Art Legend Chuck Close Talks About Painting, The Plain Dealer, September 1, 2009

- ↑ Chuck Close: Photographs, 23 July – 4 September 1999 White Cube, London.

- ↑ Chuck Close Pace Prints, New York.

- ↑ Thompson, Graham: American Culture in the 1980s (Twentieth Century American Culture) Edinburgh University Press, 2007

- ↑ For Chuck Close, an Evolving Journey Through the Faces of Others PBS Newshour July 6, 2010

- ↑ Yuskavage, Lisa. "Chuck Close", "BOMB Magazine", Summer, 1995. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ O'Hagan, Sean Head Master, The Observer, October 9, 2005

- ↑ Christian Viveros-Faune (July 18, 2012), A Visit With Art-World Hero Chuck Close Village Voice.

- ↑ Chronicles of Courage: Very Special Artists.

- ↑ Martha Schwendener (September 27, 2013), Works in Conversation With Photography New York Times.

- ↑ Scarlet Cheng (January 21, 2007), Proof is in the printing Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Genocchio, B: Prints That Say Bold and Eclectic, The New York Times, March 4, 2009

- 1 2 Chuck Close White Cube, London.

- ↑ Close, Chuck; Terrie Sultan. ""Chuck Close & Terrie Sultan" Interview at Strand Bookstore, May 1, 2014".

- 1 2 "Chuck Close: Up Close at Guild Hall." Weinreich, Regina: the Huffington Post. August 10, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- ↑ "Art Review: Sumptuous Portraits by Chuck Close at Guild Hall Museum". Hamptons Art Hub. Retrieved on 2013-10-08.

- ↑ "Press Release: Chuck Close." Pace Gallery. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- ↑ "After Decades of Pixel Painting, Chuck Close Goes Truly Digital." Co.Design. Retrieved on 2013-10-08.

- ↑ "Interface: American Master Chuck Close." Kelly, Brian: Long Island Pulse Magazine. September 20, 2013. Retrieved on 2013-10-08.

- 1 2 "A Review of 'Chuck Close – Recent Works,' at Guild Hall Museum." Schwendener, Martha: The New York Times, September 27, 2013. Retrieved on 2013-10-08.

- ↑ Finch, Christopher (2007). Chuck Close: Work. Prestel. p. 286. ISBN 978-3-7913-3676-3.

- ↑ "Artist's Portrait of Kate Moss Dazzles." Britt, Douglas: Houston Chronicle, October 29, 2008. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- ↑ "Capital Roundup." artnet Magazine. Retrieved on 2009-04-09.

- ↑ "Chuck Close is Visual Magic at Guild Hall in East Hampton." Weiss, Marion Wolberg: Dan's Papers. August 30, 2013. Retrieved on 2013-10-08.

- ↑ Ben Yakas (2014-01-22). "Here's What The Second Avenue Subway Will Look Like When It's Filled With Art". Gothamist. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- ↑ Noreen Malone (May 14, 2012), Chuck Close Will Make the Second Avenue Subway Pretty. New York Magazine.

- ↑ The 2014 Vanity Fair Hollywood Portfolio Vanity Fair's, March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Chuck Close: Nudes 1967–2014, February 28 – March 29, 2014 Pace Gallery, New York.

- ↑ Chuck Close, Big Self-Portrait (1967–1968) Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

- ↑ Mary Abbe (June 5, 2012), Former Walker director Martin Friedman toasted in New York Star Tribune.

- ↑ Carol Vogel (January 31, 1996), Chuck Close to Get a Show at the Modern New York Times.

- ↑ Phoebe Hoban (March 1, 1998), Artists, In Paint and In Person New York Times.

- ↑ Michael Kimmelman (February 27, 1998), Playful Portraits Conveying Enigmatic Messages New York Times.

- 1 2 Chuck Close Named 2009 Harman Eisner Artist In Residence Aspen Institute.

- ↑ http://whitecube.com/exhibitions/chuck_close_prints_process_and_collaboration_bermondsey_2013/

- ↑ New York artist Chuck Close on painting 'face blind', Sasha Koloff, ABC News Online, 3 December 2014

- ↑ "Siri Engberg". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ↑ Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts Archived March 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jennifer Steinhauer (February 25, 2003), New York: Manhattan: Mayor Names Cultural Advisers New York Times.

- ↑ Charles McGrath (April 22, 2005), A Portraitist Whose Canvas Is a Piano New York Times.

- ↑ The Pace Gallery website

- ↑ Carol Vogel (November 17, 1999), Auction Sets Records for 18 Contemporary Artists New York Times.

- ↑ Carly Berwick (May 11, 2005), Contemporary Art Market Returns to Sanity New York Sun.

- ↑ Wall Street Journal

- ↑

- ↑ Wendy Goodman (May 28, 2007), Buy, Rip, Repeat. New York Magazine.

- ↑ "NYSCF Exclusive Online Art Auction Now Closed".

- ↑ "You Can Buy Chuck Close's Tapestry Portrait of Barack Obama for $100,000" artinfo.com. Retrieved on 2013-02-13.

- ↑ "Chuck Close, President Obama, and an Art Sale" newyorker.com. Retrieved on 2013-02-13.

- ↑ Bahrenburg, Genevieve. "Up Close and Personal: An Unexpected Sitting with Chuck Close". Vogue. Conde Nast.

- ↑ "Feedie Foodies: The Lunchbox Fund's 2013 Benefit". Vogue. Conde Nast.

- ↑ "Finch welcomes artist Chuck Close to Park City". The Bridgeport News.

- ↑ Roberta Smith (August 29, 2006), Marion Cajori, 56, Filmmaker Who Explored Artistic Process, Dies New York Times.

- ↑ Matt Zoller Seitz (December 26, 2007), Master Portraitist, Writ Large Himself New York Times.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Benjamin (January 2011). "Art Books In Review: How We Talk About Chuck Close". The Brooklyn Rail.

Sources

- Bartman, William; Kesten, Joanne, eds. (1997). The Portraits Speak: Chuck Close in Conversation with 27 of his subjects. A.R.T. Press, New York. ISBN 0-923183-18-3.

- Greenberg, Jan; Sandra Jordan (1998). Chuck Close Up Close. DK Publishing. ISBN 0-7894-2658-7.

- Greenough, Sarah; Nelson, Andrea; Kennel, Sarah; Waggoner, Diane; Ureña, Leslie (2015). The Memory of Time: Contemporary Photographs at the National Gallery of Art. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0500544495.

- Wei, Lilly (essay) (2009). Chuck Close: Selected Paintings and Tapestries 2005–2009. PaceWildenstein. ISBN 978-1-930743-99-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Chuck Close |

- Personal Website

- Pace Gallery Page

- Chuck Close at the Museum of Modern Art

- Chuck Close at Library of Congress Authorities, with 32 catalog records

- Chuck Close: Process & Collaboration

- Chuck Close at the Walker Art Center