Catalase

| Catalase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Catalase | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00199 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR011614 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00395 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 7cat | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 7cat | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 435 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 3e4w | ||||||||

| CDD | cd00328 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Catalase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 1.11.1.6 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9001-05-2 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / EGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals). It catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen.[3] It is a very important enzyme in protecting the cell from oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Likewise, catalase has one of the highest turnover numbers of all enzymes; one catalase molecule can convert millions of hydrogen peroxide molecules to water and oxygen each second.[4]

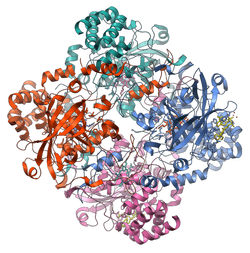

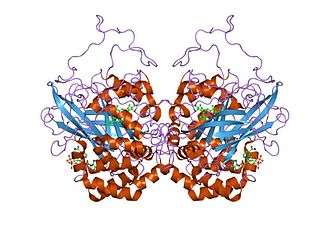

Catalase is a tetramer of four polypeptide chains, each over 500 amino acids long.[5] It contains four porphyrin heme (iron) groups that allow the enzyme to react with the hydrogen peroxide. The optimum pH for human catalase is approximately 7,[6] and has a fairly broad maximum (the rate of reaction does not change appreciably at pHs between 6.8 and 7.5).[7] The pH optimum for other catalases varies between 4 and 11 depending on the species.[8] The optimum temperature also varies by species.[9]

Structure

Human catalase forms a tetramer composed of four subunits, each of which can be conceptually divided into four domains.[10] The extensive hydrophobic core of each subunit is generated by an eight-stranded antiparallel b-barrel (b1-8), with nearest neighbor connectivity capped by b-barrel loops on one side and a9 on the other.[10] A helical domain at one face of the b-barrel is composed of four C-terminal helices (a16, a17, a18, and a19) and four helices derived from residues between b4 and b5 (a4, a5, a6, and a7).[10]

History

Catalase was not noticed until 1818 when Louis Jacques Thénard, who discovered H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide), suggested its breakdown is caused by an unknown substance. In 1900, Oscar Loew was the first to give it the name catalase, and found it in many plants and animals.[11] In 1937 catalase from beef liver was crystallised by James B. Sumner and Alexander Dounce[12] and the molecular weight was found in 1938.[13]

In 1969, the amino acid sequence of bovine catalase was discovered.[14] Then in 1981, the three-dimensional structure of the protein was revealed.[15]

Function

Action

The reaction of catalase in the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide in living tissue:

- 2 H2O2 → 2 H2O + O2

The presence of catalase in a microbial or tissue sample can be tested by adding a volume of hydrogen peroxide and observing the reaction. The formation of bubbles, oxygen, indicates a positive result. This easy assay, which can be seen with the naked eye, without the aid of instruments, is possible because catalase has a very high specific activity, which produces a detectable response. Alternative splicing may result in different protein variants.

Molecular mechanism

While the complete mechanism of catalase is not currently known,[16] the reaction is believed to occur in two stages:

- H2O2 + Fe(III)-E → H2O + O=Fe(IV)-E(.+)

- H2O2 + O=Fe(IV)-E(.+) → H2O + Fe(III)-E + O2[16]

- Here Fe()-E represents the iron center of the heme group attached to the enzyme. Fe(IV)-E(.+) is a mesomeric form of Fe(V)-E, meaning the iron is not completely oxidized to +V, but receives some "supporting electrons" from the heme ligand. This heme has to be drawn then as a radical cation (.+).

As hydrogen peroxide enters the active site, it interacts with the amino acids Asn147 (asparagine at position 147) and His74, causing a proton (hydrogen ion) to transfer between the oxygen atoms. The free oxygen atom coordinates, freeing the newly formed water molecule and Fe(IV)=O. Fe(IV)=O reacts with a second hydrogen peroxide molecule to reform Fe(III)-E and produce water and oxygen.[16] The reactivity of the iron center may be improved by the presence of the phenolate ligand of Tyr357 in the fifth iron ligand, which can assist in the oxidation of the Fe(III) to Fe(IV). The efficiency of the reaction may also be improved by the interactions of His74 and Asn147 with reaction intermediates.[16] In general, the rate of the reaction can be determined by the Michaelis-Menten equation.[17]

Catalase can also catalyze the oxidation, by hydrogen peroxide, of various metabolites and toxins, including formaldehyde, formic acid, phenols, acetaldehyde and alcohols. It does so according to the following reaction:

- H2O2 + H2R → 2H2O + R

The exact mechanism of this reaction is not known.

Any heavy metal ion (such as copper cations in copper(II) sulfate) can act as a noncompetitive inhibitor of catalase. Furthermore, the poison cyanide is a competitive inhibitor of catalase at high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide.[18] Arsenate acts as an activator.[19] Three-dimensional protein structures of the peroxidated catalase intermediates are available at the Protein Data Bank. This enzyme is commonly used in laboratories as a tool for learning the effect of enzymes upon reaction rates.

Cellular role

Hydrogen peroxide is a harmful byproduct of many normal metabolic processes; to prevent damage to cells and tissues, it must be quickly converted into other, less dangerous substances. To this end, catalase is frequently used by cells to rapidly catalyze the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into less-reactive gaseous oxygen and water molecules.[20]

The true biological significance of catalase is not always straightforward to assess: Mice genetically engineered to lack catalase are phenotypically normal, indicating this enzyme is dispensable in animals under some conditions.[21] A catalase deficiency may increase the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes.[22][23] Some humans have very low levels of catalase (acatalasia), yet show few ill effects. The predominant scavengers of H2O2 in normal mammalian cells are likely peroxiredoxins rather than catalase.

Human catalase works at an optimum temperature of 45 °C.[7] In contrast, catalase isolated from the hyperthermophile archaeon Pyrobaculum calidifontis has a temperature optimum of 90 °C.[24]

Catalase is usually located in a cellular, bipolar environment organelle called the peroxisome.[25] Peroxisomes in plant cells are involved in photorespiration (the use of oxygen and production of carbon dioxide) and symbiotic nitrogen fixation (the breaking apart of diatomic nitrogen (N2) to reactive nitrogen atoms). Hydrogen peroxide is used as a potent antimicrobial agent when cells are infected with a pathogen. Catalase-positive pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Legionella pneumophila, and Campylobacter jejuni, make catalase to deactivate the peroxide radicals, thus allowing them to survive unharmed within the host.[26]

Catalase contributes to ethanol metabolism in the body after ingestion of alcohol, but it only breaks down a small fraction of the alcohol in the body.[27]

Distribution among organisms

The large majority of known organisms use catalase in every organ, with particularly high concentrations occurring in the liver. One unique use of catalase occurs in the bombardier beetle. This beetle has two sets of chemicals ordinarily stored separately in its paired glands. The larger of the pair, the storage chamber or reservoir, contains hydroquinones and hydrogen peroxide, whereas the smaller of the pair, the reaction chamber, contains catalases and peroxidases. To activate the noxious spray, the beetle mixes the contents of the two compartments, causing oxygen to be liberated from hydrogen peroxide. The oxygen oxidizes the hydroquinones and also acts as the propellant.[28] The oxidation reaction is very exothermic (ΔH = −202.8 kJ/mol) which rapidly heats the mixture to the boiling point.[29]

Catalase is also universal among plants, and many fungi are also high producers of the enzyme.[30]

Almost all aerobic microorganisms use catalase. It is also present in some anaerobic microorganisms, such as Methanosarcina barkeri.[31]

According to a March 2015 Scientific American Special Report on Aging article, laboratory mice at a University of Washington laboratory who produced more catalase, which is an antioxidant, lived longer. Research on the topic both supports and cautions against the benefit of antioxidants for health effects on aging.

Clinical significance and application

Catalase is used in the food industry for removing hydrogen peroxide from milk prior to cheese production.[32] Another use is in food wrappers where it prevents food from oxidizing.[33] Catalase is also used in the textile industry, removing hydrogen peroxide from fabrics to make sure the material is peroxide-free.[34]

A minor use is in contact lens hygiene - a few lens-cleaning products disinfect the lens using a hydrogen peroxide solution; a solution containing catalase is then used to decompose the hydrogen peroxide before the lens is used again.[35] Recently, catalase has also begun to be used in the aesthetics industry. Several mask treatments combine the enzyme with hydrogen peroxide on the face with the intent of increasing cellular oxygenation in the upper layers of the epidermis.

Catalase test

The catalase test is also one of the main three tests used by microbiologists to identify species of bacteria. The presence of catalase enzyme in the test isolate is detected using hydrogen peroxide. If the bacteria possess catalase (i.e., are catalase-positive), when a small amount of bacterial isolate is added to hydrogen peroxide, bubbles of oxygen are observed.

The catalase test is done by placing a drop of hydrogen peroxide on a microscope slide. Using an applicator stick, a scientist touches the colony, and then smears a sample into the hydrogen peroxide drop.

- If the mixture produces bubbles or froth, the organism is said to be 'catalase-positive'. Staphylococci[36] and Micrococci[37] are catalase-positive. Other catalase-positive organisms include Listeria, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Burkholderia cepacia, Nocardia, the family Enterobacteriaceae (Citrobacter, E. coli, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Shigella, Yersinia, Proteus, Salmonella, Serratia), Pseudomonas, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, and Rhodococcus equi.

- If not, the organism is 'catalase-negative'. Streptococcus[38] and Enterococcus spp. are catalase-negative.

While the catalase test alone cannot identify a particular organism, combined with other tests, such as antibiotic resistance, it can aid identification. The presence of catalase in bacterial cells depends on both the growth condition and the medium used to grow the cells.

Capillary tubes may also be used. A small amount of bacteria is collected on the end of the capillary tube (it is essential to ensure that the end is not blocked, otherwise it may present a false negative). The opposite end is then dipped into hydrogen peroxide which will draw up the liquid (through capillary action), and turned upside down, so the bacterial end is closest to the bench. A few taps of the arm should then move the hydrogen peroxide closer to the bacteria. When the hydrogen peroxide and bacteria are touching, bubbles may begin to rise, giving a positive catalase result.

Gray hair

According to recent scientific studies, low levels of catalase may play a role in the graying process of human hair. Hydrogen peroxide is naturally produced by the body and catalase breaks it down. If catalase levels decline, hydrogen peroxide cannot be broken down as well. This allows the hydrogen peroxide to bleach the hair from the inside out. This finding is under investigation in hopes of developing cosmetic treatments for graying hair based on catalase supplements.[39][40][41]

Interactions

Catalase has been shown to interact with the ABL2 [42] and Abl genes.[42] Infection with the murine leukemia virus causes catalase activity to decline in the lungs, heart and kidneys of mice. Conversely, dietary fish oil increased catalase activity in the heart, and kidneys of mice. [43]

See also

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Chelikani P, Fita I, Loewen PC (Jan 2004). "Diversity of structures and properties among catalases". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 61 (2): 192–208. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3206-5. PMID 14745498.

- ↑ Goodsell DS (2004-09-01). "Catalase". Molecule of the Month. RCSB Protein Data Bank. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- ↑ Boon EM, Downs A, Marcey D. "Catalase: H2O2: H2O2 Oxidoreductase". Catalase Structural Tutorial Text. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ↑ Maehly AC, Chance B (1954). "The assay of catalases and peroxidases". Methods of Biochemical Analysis. Methods of Biochemical Analysis. 1: 357–424. doi:10.1002/9780470110171.ch14. ISBN 978-0-470-11017-1. PMID 13193536.

- 1 2 Aebi H (1984). Aebi H, ed. "Catalase in vitro". Methods in Enzymology. Methods in Enzymology. 105: 121–6. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3. ISBN 0-12-182005-X. PMID 6727660.

- ↑ "EC 1.11.1.6 - catalase". BRENDA: The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System. Department of Bioinformatics and Biochemistry, Technische Universität Braunschweig. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Toner K, Sojka G, Ellis R. "A Quantitative Enzyme Study; CATALASE". bucknell.edu. Archived from the original on 2000-06-12. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- 1 2 3 Putnam CD, Arvai AS, Bourne Y, Tainer JA (February 2000). "Active and inhibited human catalase structures: ligand and NADPH binding and catalytic mechanism". Journal of Molecular Biology. 296 (1): 295–309. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3458. PMID 10656833.

- ↑ Loew O (May 1900). "A New Enzyme of General Occurrence in Organisms". Science. 11 (279): 701–2. doi:10.1126/science.11.279.701. PMID 17751716.

- ↑ Sumner JB, Dounce AL (Apr 1937). "CRYSTALLINE CATALASE". Science. 85 (2206): 366–7. doi:10.1126/science.85.2206.366. PMID 17776781.

- ↑ Sumner JB, Gralén N (Mar 1938). "The molecular weight of crystalline catalase". Science. 87 (2256): 284. doi:10.1126/science.87.2256.284. PMID 17831682.

- ↑ Schroeder WA, Shelton JR, Shelton JB, Robberson B, Apell G (May 1969). "The amino acid sequence of bovine liver catalase: a preliminary report". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 131 (2): 653–5. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(69)90441-X. PMID 4892021.

- ↑ Murthy MR, Reid TJ, Sicignano A, Tanaka N, Rossmann MG (Oct 1981). "Structure of beef liver catalase". Journal of Molecular Biology. 152 (2): 465–99. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(81)90254-0. PMID 7328661.

- 1 2 3 4 Boon EM, Downs A, Marcey D. "Proposed Mechanism of Catalase". Catalase: H2O2: H2O2 Oxidoreductase: Catalase Structural Tutorial. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ↑ Maass E (1998-07-19). "How does the concentration of hydrogen peroxide affect the reaction". MadSci Network. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ↑ Ogura, Y.; Yamazaki, I. (Aug 1983). "Steady-state kinetics of the catalase reaction in the presence of cyanide". J Biochem. 94 (2): 403–8. PMID 6630165.

- ↑ Kertulis-Tartar GM, Rathinasabapathi B, Ma LQ (Oct 2009). "Characterization of glutathione reductase and catalase in the fronds of two Pteris ferns upon arsenic exposure". Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 47 (10): 960–5. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.05.009. PMID 19574057.

- ↑ Gaetani GF, Ferraris AM, Rolfo M, Mangerini R, Arena S, Kirkman HN (Feb 1996). "Predominant role of catalase in the disposal of hydrogen peroxide within human erythrocytes". Blood. 87 (4): 1595–9. PMID 8608252.

- ↑ Ho YS, Xiong Y, Ma W, Spector A, Ho DS (Jul 2004). "Mice lacking catalase develop normally but show differential sensitivity to oxidant tissue injury". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (31): 32804–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M404800200. PMID 15178682.

- ↑ Góth L, Bigler WN (Oct 2001). "Blood catalase deficiency and diabetes in Hungary". Diabetes Care. 24 (10): 1839–40. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.10.1839. PMID 11574451.

- ↑ Góth L (Dec 2008). "Catalase deficiency and type 2 diabetes". Diabetes Care. 31 (12): e93. doi:10.2337/dc08-1607. PMID 19033415.

- ↑ Amo T, Atomi H, Imanaka T (Jun 2002). "Unique presence of a manganese catalase in a hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrobaculum calidifontis VA1". Journal of Bacteriology. 184 (12): 3305–12. doi:10.1128/JB.184.12.3305-3312.2002. PMC 135111

. PMID 12029047.

. PMID 12029047. - ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "Peroxisomes". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ↑ Srinivasa Rao PS, Yamada Y, Leung KY (Sep 2003). "A major catalase (KatB) that is required for resistance to H2O2 and phagocyte-mediated killing in Edwardsiella tarda". Microbiology. 149 (Pt 9): 2635–44. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26478-0. PMID 12949187.

- ↑ http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AA72/AA72.htm

- ↑ Eisner T, Aneshansley DJ (Aug 1999). "Spray aiming in the bombardier beetle: photographic evidence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (17): 9705–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.17.9705. PMC 22274

. PMID 10449758.

. PMID 10449758. - ↑ Beheshti N, McIntosh AC (2006). "A biomimetic study of the explosive discharge of the bombardier beetle" (PDF). Int. Journal of Design & Nature. 1 (1): 1–9.

- ↑ Isobe K, Inoue N, Takamatsu Y, Kamada K, Wakao N (Jan 2006). "Production of catalase by fungi growing at low pH and high temperature". Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 101 (1): 73–6. doi:10.1263/jbb.101.73. PMID 16503295.

- ↑ Brioukhanov AL, Netrusov AI, Eggen RI (Jun 2006). "The catalase and superoxide dismutase genes are transcriptionally up-regulated upon oxidative stress in the strictly anaerobic archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri". Microbiology. 152 (Pt 6): 1671–7. doi:10.1099/mic.0.28542-0. PMID 16735730.

- ↑ "Catalase". Worthington Enzyme Manual. Worthington Biochemical Corporation. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Hengge A (1999-03-16). "Re: how is catalase used in industry?". General Biology. MadSci Network. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ "textile industry". Case study 228. International Cleaner Production Information Clearinghouse. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ US patent 5521091, Cook JN, Worsley JL, "Compositions and method for destroying hydrogen peroxide on contact lens", issued 1996-05-28

- ↑ Rollins DM (2000-08-01). "Bacterial Pathogen List". BSCI 424 Pathogenic Microbiology. University of Maryland. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Johnson M. "Catalase Production". Biochemical Tests. Mesa Community College. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Fox A. "Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococci". University of South Carolina. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ "Why Hair Turns Gray Is No Longer A Gray Area: Our Hair Bleaches Itself As We Grow Older". Science News. ScienceDaily. 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Hitti M (2009-02-25). "Why Hair Goes Gray". Health News. WebMD. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Wood JM, Decker H, Hartmann H, Chavan B, Rokos H, Spencer JD, Hasse S, Thornton MJ, Shalbaf M, Paus R, Schallreuter KU (Jul 2009). "Senile hair graying: H2O2-mediated oxidative stress affects human hair color by blunting methionine sulfoxide repair". FASEB Journal. 23 (7): 2065–75. doi:10.1096/fj.08-125435. PMID 19237503.

- 1 2 Cao C, Leng Y, Kufe D (Aug 2003). "Catalase activity is regulated by c-Abl and Arg in the oxidative stress response". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (32): 29667–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301292200. PMID 12777400.

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0271531700002141

External links

- "GenAge entry for CAT (Homo sapiens)". Human Ageing Genomic Resources. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- "Catalase". MadSci FAQ. madsci.org. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- "Catalase and oxidase test video". Regnvm Prokaryotae. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- "EC 1.11.1.6 - catalase". Brenda: The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- "PeroxiBase - The peroxidase database". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Archived from the original on 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- "Catalase Procedure". MicrobeID.com. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- "Catalase Molecule of the Month". Protein Data Bank. Retrieved 2013-01-08.