Carl Perkins

| Carl Perkins | |

|---|---|

Carl Perkins, c. 1956 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Carl Lee Perkins |

| Born |

April 9, 1932 Tiptonville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died |

January 19, 1998 (aged 65) Jackson, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter, guitarist |

| Instruments | Guitar, vocals |

| Years active | 1946–1997 |

| Labels | Sun, London, Columbia, Mercury |

| Associated acts |

Perkins Brothers Band Johnny Cash Elvis Presley Jerry Lee Lewis |

Carl Lee Perkins (April 9, 1932 – January 19, 1998)[1] was an American singer-songwriter who recorded most notably at the Sun Studio, in Memphis, Tennessee, beginning in 1954. His best-known song is "Blue Suede Shoes".

According to Charlie Daniels, "Carl Perkins' songs personified the rockabilly era, and Carl Perkins' sound personifies the rockabilly sound more so than anybody involved in it, because he never changed."[2] Perkins' songs were recorded by artists (and friends) as influential as Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, and Johnny Cash, which further established his place in the history of popular music. Paul McCartney claimed that "if there were no Carl Perkins, there would be no Beatles."[3]

Called "the King of Rockabilly", he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, the Memphis Music Hall of Fame, and the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. He also received a Grammy Hall of Fame Award.

Biography

Early life

Perkins was born near Tiptonville, Tennessee, the son of poor sharecroppers, Buck and Louise Perkins (misspelled on his birth certificate as "Perkings").[4] He grew up hearing Southern gospel music sung by whites in church and by African-American field workers when he started working in the cotton fields[5] at the age of six. During spring and autumn, the school day would be followed by several hours of work in the fields. During the summer, workdays were 12–14 hours, "from can to can't." Perkins and his brother Jay together would earn 50 cents a day. With all family members working and not having any credit, there was enough money for beans and potatoes, some tobacco for Perkins's father, and occasionally the luxury of a five-cent bag of hard candy.[6]

On Saturday nights Perkins would listen to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio with his father. Roy Acuff's broadcasts on the Opry inspired him to ask his parents for a guitar.[7] They could not afford a real guitar, so Buck Perkins fashioned one from a cigar box and a broomstick. When a neighbor in tough straits offered to sell his dented and scratched Gene Autry model guitar with worn-out strings, Buck purchased it for a couple of dollars.

For the next year Perkins taught himself parts of Acuff's "Great Speckled Bird" and "The Wabash Cannonball", which he had heard on the Opry. He also cited the fast playing and vocals of Bill Monroe as an early influence.[8]

Perkins began learning more about playing the guitar from John Westbrook, a field worker who befriended him. "Uncle John", as Perkins called him, was an African-American in his sixties, who played blues and gospel music on his battered acoustic guitar. Uncle John advised Perkins when playing the guitar to "Get down close to it. You can feel it travel down the strangs, come through your head and down to your soul where you live. You can feel it. Let it vib-a-rate." Because Perkins could not afford new strings when they broke, he retied them. The knots would cut into his fingers when he tried to slide to another note, so he began bending the notes, stumbling onto a type of blue note.[2][9]

Perkins was recruited to be a member of the Lake County Fourth Grade Marching Band, and because his family lacked the money to buy them, he was given a new white shirt, cotton pants, a white band cap and a red cape by the woman in charge of the band, Lee McCutcheon.[10]

In January 1947, Buck Perkins moved his family from Lake County, Tennessee, to Madison County, Tennessee. A new radio that ran on house current rather than a battery and the proximity of Memphis made it possible for Perkins to hear a greater variety of music.[11] At age fourteen, using the I-IV-V chord progression common in country songs of the day,[12] he wrote a song that came to be known around Jackson as "Let Me Take You to the Movie, Magg"[13] (the song would convince Sam Phillips to sign Perkins to his Sun Records label).

Beginnings as a performer

Perkins and his brother Jay had their first paying job (in tips) as entertainers at the Cotton Boll tavern on Highway 45, twelve miles south of Jackson, starting on Wednesday nights during late 1946. Perkins was 14 years old. One of the songs they played was an up-tempo country blues shuffle version of Bill Monroe's "Blue Moon of Kentucky". Free drinks were one of the perks of playing in a tavern, and Perkins drank four beers that first night. Within a month Carl and Jay began playing Friday and Saturday nights at the Sand Ditch tavern, near the western boundary of Jackson. Both places were the scene of occasional fights, and both of the Perkins brothers gained a reputation as fighters.[14]

During the next couple of years the Perkins brothers began playing other taverns around Bemis and Jackson, including El Rancho, the Roadside Inn, and the Hilltop, as they became better known. Carl persuaded his brother Clayton to play the upright bass to complete the sound of the band.[15]

Perkins began performing regularly on WTJS-AM in Jackson during the late 1940s as a sometime member of the Tennessee Ramblers. He also appeared on Hayloft Frolic, on which he performed two songs, sometimes including "Talking Blues" as done by Robert Lunn on the Grand Ole Opry. Perkins and then his brothers began appearing on The Early Morning Farm and Home Hour. Positive listener response resulted in a 15-minute segment sponsored by Mother's Best Flour. By the end of the 1940s, the Perkins Brothers were the best-known band in the Jackson area.[16]

Perkins had day jobs during most of these early years, picking cotton and later working at Day's Dairy in Malesus, at a mattress factory and in a battery plant. He worked as a pan greaser for the Colonial Baking Company in 1951 and 1952.[17][18]

In January 1953, Perkins married Valda Crider, whom he had known for a number of years. When his job at the bakery was reduced to part-time, Valda, who had her own job, encouraged Perkins to begin working the taverns full-time. He began playing six nights a week. Later the same year he added W.S. "Fluke" Holland to the band as a drummer. Halder had no previous experience as a musician but had a good sense of rhythm.[19]

Malcolm Yelvington, who remembered the Perkins Brothers when they played in Covington, Tennessee, in 1953, noted that Carl had a very unusual blues-like style all his own.[20] By 1955 Perkins had made tapes of his material with a borrowed tape recorder, and he sent them to companies such as Columbia and RCA, with addresses like "Columbia Records, New York City". "I had sent tapes to RCA and Columbia and had never heard a thing from 'em."[21]

In July 1954, Perkins and his wife heard a new release of "Blue Moon of Kentucky" by Elvis Presley, Scotty Moore and Bill Black on the radio.[22] As the song faded out, Perkins said, "There's a man in Memphis who understands what we're doing. I need to go see him."[23] According to another telling of the story, it was Valda who told him that he should go to Memphis.[24] Later, Presley told Perkins that he had traveled to Jackson and seen Perkins and his group playing at El Rancho.[21]

Years later the musician Gene Vincent told an interviewer that, rather than "Blue Moon of Kentucky" being a "new sound", "a lot of people were doing it before that, especially Carl Perkins."[25]

Sun Records

Perkins successfully auditioned for Sam Phillips at Sun Records during early October 1954. "Movie Magg" and "Turn Around" were released on the Phillips-owned Flip label (151) on March 19, 1955.[26] "Turn Around" became a regional success.[1] With the song getting airplay across the South and Southwest, Perkins was booked to appear along with Elvis Presley at theaters in Marianna and West Memphis, Arkansas. Commenting on the audience reaction to both Presley and himself, Perkins said, "When I'd jump around they'd scream some, but they were gettin' ready for him. It was like TNT, man, it just exploded. All of a sudden the world was wrapped up in rock."[27]

Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Two were the next musicians to be added to the performances by Sun musicians. During the summer of 1955 there were junkets to Little Rock, Forrest City, Arkansas, and Corinth and Tupelo, Mississippi. Again performing at El Rancho, the Perkins brothers were involved in an automobile accident in Woodside, Delaware. A friend, who had been driving, was pinned by the steering wheel. Perkins managed to drag him from the car, which had begun burning. Clayton had been thrown from the car but was not injured seriously.[28]

Another Perkins song, "Gone Gone Gone",[29][30] released by Sun in October 1955,[31] was also a regional success. It was a "bounce blues in flavorsome combined country and r.&b. idioms".[32] It was backed by the more traditional "Let the Jukebox Keep On Playing", complete with fiddle, "Western boogie" bass line, steel guitar and weepy vocal.[33]

Commenting on Perkins' playing, Sam Phillips has been quoted as saying, "I knew that Carl could rock and in fact he told me right from the start that he had been playing that music before Elvis came out on record ... I wanted to see whether this was someone who could revolutionize the country end of the business."[34]

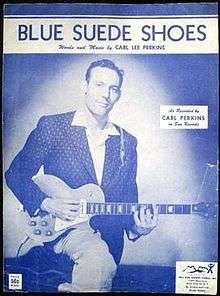

Also in the autumn of 1955, Perkins wrote "Blue Suede Shoes"[5] after seeing a dancer get angry with his date for scuffing up his shoes.[35] Several weeks later, on December 19, 1955, Perkins and his band recorded the song during a session at Sun Studio in Memphis. Phillips suggested changes to the lyrics ("Go, cat, go") and the band changed the end of the song to a "boogie vamp".[36] Presley left Sun for a larger opportunity with RCA in November, and on December 19, 1955, Phillips, who had begun recording Perkins in late 1954, told Perkins, "Carl Perkins, you're my rockabilly cat now."[37] Released on January 1, 1956, "Blue Suede Shoes" was a massive chart success. In the United States, it reached No. 1 on Billboard magazine's country music charts (the only No. 1 success he would have) and No. 2 on Billboard's Best Sellers popular music chart. On March 17, Perkins became the first country artist to reach No. 3 on the rhythm and blues charts.[36][38] That night, Perkins performed the song on ABC-TV's Ozark Jubilee, his television debut (Presley performed it for the second time that same night on CBS-TV's Stage Show; he'd first sung it on the program on February 11).

In the United Kingdom, the song became a Top Ten hit, reaching No. 10 on the British charts. It was the first record by a Sun artist to sell a million copies. The B side, "Honey Don't", was covered by the Beatles,[5] Wanda Jackson and (in the 1970s) T. Rex. John Lennon sang lead on the song when the Beatles performed it before it was given to Ringo Starr to sing. Lennon also performed the song on the Lost Lennon Tapes.[38]

Road accident

After playing a show in Norfolk, Virginia, on March 21, 1956, the Perkins Brothers Band headed to New York City for a March 24 appearance on NBC-TV's Perry Como Show. Shortly before sunrise on March 22, on Route 13 between Dover and Woodside, Delaware, Stuart Pinkham (also known as Richard Stuart and Poor Richard) assumed duties as driver. After hitting the back of a pickup truck, their car went into a ditch containing about a foot of water, and Perkins was left lying face down in the water. Drummer Holland rolled Perkins over, saving him from drowning. He had suffered three fractured vertebrae in his neck, a severe concussion, a broken collar bone, and lacerations all over his body in the crash. Perkins remained unconscious for an entire day. The driver of the pickup truck, Thomas Phillips, a 40-year-old farmer, died when he was thrown into the steering wheel.[39] Jay Perkins had a fractured neck and severe internal injuries; he never fully recovered and died in 1958.

On March 23, Bill Black, Scotty Moore and D.J. Fontana, the members of Elvis's band, visited Perkins on their way to New York to appear with Presley the next day. D.J. Fontana recalled Perkins saying, "Of all the people, I looked up and there you guys are. You looked like a bunch of angels coming to see me."[40] Black told him, "Hey man, Elvis sends his love", and lit a cigarette for him, even though the patient in the next bed was in an oxygen tent. A week later, Perkins was given a telegram from Presley (which had arrived on March 23), wishing him a speedy recovery.[41]

Sam Philips had planned to surprise Perkins with a gold record on The Perry Como Show. "Blue Suede Shoes" had sold more than 500,000 copies by March 22.[42] Now, while Perkins recuperated from his injuries, "Blue Suede Shoes" reached No. 1 on regional pop, R&B, and country charts. It also reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and country charts. Elvis Presley's "Heartbreak Hotel" was number one on the pop and country charts at that time, but "Blue Suede Shoes" did better than "Heartbreak" on the R&B charts. By mid-April, more than one million copies of "Blue Suede Shoes" had been sold.[43]

On April 3, while still recuperating in Jackson, Perkins watched Presley perform "Blue Suede Shoes" on his first appearance on The Milton Berle Show, which was his third performance of the song on national television.[44][45] He also made references to it twice during an appearance on The Steve Allen Show. Although his version became more famous than Perkins', it reached only as high as No. 20 on Billboard's pop chart.[46]

Return to recording and touring

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Perkins returned to live performances on April 21, 1956, beginning with an appearance in Beaumont, Texas, with the "Big D Jamboree" tour.[47] Before he resumed touring, Sam Phillips arranged a recording session at Sun, with Ed Cisco filling in for the still-recuperating Jay. By mid-April, "Dixie Fried", "Put Your Cat Clothes On", "Right String, Wrong Yo-Yo", "You Can't Make Love to Somebody", "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby", and "That Don't Move Me" had been recorded.[48]

Beginning early that summer, Perkins was paid $1,000 to play just two songs a night on the extended tour of "Top Stars of '56". Other performers on the tour were Chuck Berry and Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. When Perkins and the group entered the stage in Columbia, South Carolina, he was appalled to see a teenager with a bleeding chin pressed against the stage by the crowd. During the first guitar intermission of "Honey Don't" they were waved offstage and into a vacant dressing room behind a double line of police officers. Perkins was quoted as saying, "It was dangerous. Lot of kids got hurt. There was a lot of rioting going on, just crazy, man! The music drove 'em insane." Appalled by what he had seen and experienced, Perkins left the tour.[49] Appearing with Gene Vincent and Lillian Briggs in a "rock 'n' roll show", he helped pull 39,872 people to the Reading Fair in Pennsylvania on a Tuesday night in late September. A full grandstand and one thousand people stood in a heavy rain to hear Perkins and Briggs at the Brockton Fair in Massachusetts.[50]

Sun issued more Perkins songs in 1956: "Boppin' the Blues"/"All Mama's Children" (Sun 243), the B side co-written with Johnny Cash, "Dixie Fried"/"I'm Sorry, I'm Not Sorry" (Sun 249). "Matchbox"/"Your True Love" (Sun 261)[51] came out in February 1957.[31] "Boppin' the Blues" reached No. 47 on the Cashbox pop singles chart, No. 9 on the Billboard country and western chart, and No. 70 on the Billboard Top 100 chart.

"Matchbox" is considered a rockabilly classic. The day it was recorded, Elvis Presley visited the studio. Perkins, Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash (who left early) spent more than an hour singing gospel, country and rhythm-and-blues songs while a tape rolled.[5] The performers at this casual session were called the Million Dollar Quartet by a local newspaper the next day. These recordings were released on CD in 1990.[1]

On February 2, 1957, Perkins again appeared on Ozark Jubilee, singing "Matchbox" and "Blue Suede Shoes". He also made at least two appearances on Town Hall Party in Compton, California, in 1957,[52] singing both songs. Those performances were included in the Western Ranch Dance Party series filmed and distributed by Screen Gems.

He released "That's Right", co-written with Johnny Cash, backed with the ballad "Forever Yours", as Sun single 274 in August 1957. Neither side made it onto the charts.

The 1957 film Jamboree included a Perkins performance of "Glad All Over" (not to be confused with the Dave Clark Five song of the same name), that ran 1:55. "Glad All Over", written by Aaron Schroeder, Sid Tepper, and Roy C. Bennett,[53] was released by Sun in January 1958.[54]

Life after Sun

In 1958, Perkins moved to Columbia Records, for which he recorded "Jive After Five", "Rockin' Record Hop", "Levi Jacket (And a Long Tail Shirt)", "Pop, Let Me Have the Car", "Pink Pedal Pushers", "Any Way the Wind Blows", "Hambone", "Pointed Toe Shoes", "Sister Twister", "L-O-V-E-V-I-L-L-E" and other songs.[31]

In 1959, he wrote the country-and-western song "The Ballad of Boot Hill" for Johnny Cash, who recorded it on an EP for Columbia Records. In the same year, Perkins was cast in a Filipino movie produced by People's Pictures, Hawaiian Boy, in which he sang "Blue Suede Shoes".

He performed often at the Golden Nugget Casino in Las Vegas in 1962 and 1963. During this time he toured nine Midwestern states and made a tour in Germany.

In May 1964, Perkins toured Britain with Chuck Berry.[55] Perkins had been reluctant to undertake the tour, convinced that as forgotten as he was in America, he would be even more obscure in the U.K., and he did not want to be humiliated by drawing meager audiences. Berry assured him that they had remained much more popular in Britain since the 1950s than they had in the United States and that there would be large crowds of fans at every show. The Animals backed the two performers. On the last night of the tour, Perkins attended a party where he sat on the floor sharing stories, playing guitar, and singing songs while surrounded by the Beatles. Ringo Starr asked if he could record "Honey Don't". Perkins answered, "Man, go ahead, have at it."[56] The Beatles went on to record covers of "Matchbox", "Honey Don't" and "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby" (recorded by Perkins, adapted from a song originally recorded by Rex Griffin in 1936, with new music by Perkins; a song with the same title was recorded by Roy Newman in 1938). The Beatles recorded two versions of "Glad All Over" in 1963.[57] Another tour to Germany followed in the autumn.

He released "Big Bad Blues" backed with "Lonely Heart" as a single on Brunswick Records with the Nashville Teens in June 1964.[58]

While on tour with the Johnny Cash troupe in 1968, Perkins went on a four-day drinking binge. With the urging of Cash, he opened a show in San Diego, California, by playing four songs after seeing "four or five of me in the mirror" and while being able to see "nothin' but a blur". After drinking yet another pint of whiskey, he passed out on the tour bus. By morning he started hallucinating "big spiders, and dinosaurs, huge, and they were gonna step on me". The bus was parked on a beach at the ocean. He was tempted by yet another pint of whiskey that he had hidden. He took the bottle with him onto the beach and fell on his knees and said, "Lord, ... I'm gonna throw this bottle. I'm gonna show You that I believe in you. I sailed it into the Pacific ... I got up, I knew I had done the right thing." Perkins and Cash, who had his own problems with drugs, then gave each other support to stay sober.[59]

In 1968, Cash recorded the Perkins-written "Daddy Sang Bass" (which incorporates parts of the American standard "Will the Circle Be Unbroken") and scored No. 1 on the country music charts for six weeks. Glen Campbell also covered the song, as did the Statler Brothers and Carl Story. "Daddy Sang Bass" was a Country Music Association nominee for Song of the Year. Perkins also played lead guitar on Cash's single "A Boy Named Sue", recorded live at San Quentin prison, which went to No. 1 for five weeks on the country chart and No. 2 on the pop chart (the performance was also filmed by Granada Television for broadcast). Perkins spent a decade in Cash's touring revue, often as an opening act for Cash (as at the Folsom and San Quentin prison concerts, at which he was recorded singing "Blue Suede Shoes" and "Matchbox" before Cash took the stage; these performances were not released until the 2000s). He also appeared on the television seriesThe Johnny Cash Show. He played "Matchbox" with Cash and Derek and the Dominoes. Cash also featured Perkins in rehearsal jamming with José Feliciano and Merle Travis.

On the television program Kraft Music Hall on April 16, 1969, hosted by Cash, Perkins performed his song "Restless".[60][61]

Perkins and Bob Dylan wrote "Champaign, Illinois" in 1969. Dylan was recording in Nashville from February 12 to February 21 for his album Nashville Skyline. He met Perkins when he appeared on The Johnny Cash Show on June 7.[62] Dylan had written one verse of the song but was stuck. Perkins worked out a loping rhythm and improvised a verse-ending lyric, and Dylan said to him, "Your song. Take it. Finish it."[63] The co-authored song was included on Perkins's 1969 album On Top.[64][65]

Perkins was also united in 1969 by Columbia's Murray Krugman with a rockabilly group based in New York's Hudson Valley, the New Rhythm and Blues Quartet. Carl and NRBQ recorded "Boppin' the Blues" which featured the group backing him on songs like his staples "Turn Around" and "Boppin' the Blues" and included songs recorded separately by Perkins and NRBQ.[66] One of his TV appearances with Cash was on the popular country series Hee Haw on February 16, 1974.

Tommy Cash (brother of Johnny Cash) had a Top Ten country gospel hit in 1970 with a recording of the song "Rise and Shine", written by Perkins. It reached no. 9 on the Billboard country chart and no. 8 on the Canadian country chart. Arlene Harden had a Top 40 country hit in 1971 with the Perkins composition "True Love Is Greater Than Friendship", from the film Little Fauss and Big Halsy (1971) which reached no. 22 on the Billboard country chart and no. 33 on the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart for Al Martino that same year.

After a long legal struggle with Sam Phillips over royalties, Perkins gained ownership of his songs in the 1970s.[67]

Later years

In 1981 Perkins recorded the song "Get It" with Paul McCartney, providing vocals and playing guitar with the former Beatle. This recording was included on the chart-topping album Tug of War, released in 1982.[68] This track was also the B-side of the title track single in a slightly edited form. One source states that Perkins "wrote the song with Paul McCartney".[69] The song ends with a fade-out of Perkins's impromptu laughter.

The rockabilly revival of the 1980s helped bring Perkins back into the limelight. During 1985, he re-recorded "Blue Suede Shoes" with Lee Rocker and Jim Phantom of the Stray Cats, as part of the soundtrack for the film Porky's Revenge.

In October 1985, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Dave Edmunds, Lee Rocker, Rosanne Cash and Ringo Starr appeared with him on stage for a television special, Blue Suede Shoes: A Rockabilly Session, which was taped live at the Limehouse Studios in London. The show was shown on Channel 4 on January 1, 1986. Perkins performed 16 songs, with two encores, in an extraordinary performance. He and his friends ended the session by singing his most famous song, 30 years after its writing, which brought Perkins to tears. The concert special was a highlight of Perkins' later career and has been praised by fans for the spirited performances delivered by Perkins and his guests. The concert was released for DVD by Snapper Music in 2006.[70]

Perkins was inducted to the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1985. Wider recognition of his contribution to music came with his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987. "Blue Suede Shoes" was chosen as one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. The song also received a Grammy Hall of Fame Award. Perkins was inducted into the Rockabilly Hall of Fame in recognition of his pioneering contribution to the genre.

Perkins' only notable film performance as an actor was in John Landis's 1985 film Into the Night, a cameo-laden film that includes a scene in which characters played by Perkins and David Bowie die at each other's hand.[71]

Perkins returned to the Sun Studio in Memphis in 1986, joining Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Roy Orbison on the album Class of '55. The record was a tribute to their early years at Sun and, specifically, the Million Dollar Quartet jam session involving Perkins, Presley, Cash, and Lewis in 1956.

In 1989, Perkins co-wrote and played guitar on the Judds' No. 1 country success, "Let Me Tell You About Love". Also in that year, he signed a record deal with Platinum Records for the album Friends, Family, and Legends, featuring performances by Chet Atkins, Travis Tritt, Steve Wariner, Joan Jett and Charlie Daniels, along with Paul Shaffer and Will Lee. During the production of this album, Perkins developed throat cancer.

He again returned to Sun Studio to record with Scotty Moore, Presley's first guitar player, for the album 706 ReUNION, released by Belle Meade Records, which also featured D.J. Fontana, Marcus Van Storey and the Jordanaires. In 1993, Perkins performed with the Kentucky Headhunters in a music video remake of his song "Dixie Fried", filmed in Glasgow, Kentucky, In 1994, he teamed up with Duane Eddy and the Mavericks to contribute "Matchbox" to the AIDS benefit album Red Hot + Country, produced by the Red Hot Organization.

His last album, Go Cat Go!, released by the independent label Dinosaur Records in 1996, features Perkins singing duests with Bono, Johnny Cash, John Fogerty, George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Willie Nelson, Tom Petty, Paul Simon, and Ringo Starr.[72][73]

His last major concert performance was the Music for Montserrat all-star charity concert at London's Royal Albert Hall on September 15, 1997.

Perkins died four months later, on January 19, 1998, at the age of 65, at Jackson-Madison County Hospital in Jackson, Tennessee, from throat cancer after suffering several strokes. Among the mourners at his funeral at Lambuth University were George Harrison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Wynonna Judd, Garth Brooks, Nashville agent Jim Dallas Crouch, Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash. Perkins was interred at Ridgecrest Cemetery in Jackson.

Personal life

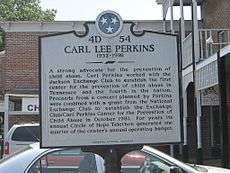

A strong advocate for the prevention of child abuse, Perkins worked with the Jackson Exchange Club to establish the first center for the prevention of child abuse in Tennessee and the fourth in the nation. Proceeds from a concert planned by Perkins were combined with a grant from the National Exchange Club to establish the Prevention of Child Abuse in October 1981. For years its annual Circle of Hope Telethon generated one quarter of the center's annual operating budget.[74]

Perkins had one daughter, Debbie, and three sons, Stan, Greg, and Steve.

Stan, his first-born son, is also a recording artist. In 2010, he joined forces with Jerry Naylor to record a duet tribute, "To Carl: Let it Vibrate". Stan has been inducted into the Rockabilly Hall of Fame.

Perkins' widow, Valda deVere Perkins, died on November 15, 2005, in Jackson.

Singer-guitarist Luther Perkins, who was also a member of Cash's touring show, was not related to Perkins.

Guitar style

As a guitarist Perkins used finger picking, imitations of the pedal steel guitar, right-handed damping (muffling strings near the bridge with the palm), arpeggios, advantageous use of open strings, single and double string bending (pushing strings across the neck to raise their pitch), chromaticism (using notes outside of the scale), country and blue licks, and tritone and other tonality clashing licks (short phrases that include notes from other keys and move in logical, often symmetric patterns).[75] A rich vocabulary of chords including sixth and thirteenth chords, ninth and add nine chords, and suspensions, show up in rhythm parts and solos. Free use of syncopations, chord anticipations (arriving at a chord change before the other players, often by an eighth-note) and crosspicking (repeating a three eighth-note pattern so that an accent falls variously on the upbeat or downbeat) are also in his bag of tricks.[76]

Legacy

Perkins wrote his autobiography, Go, Cat, Go, published in 1996, in collaboration with music writer David McGee in 1996. Plans for a biographical film were announced by Santa Monica-based production company Fastlane Entertainment.[77][78] was slated for release in 2009.

In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked Perkins number 99 on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[79]

His version of "Blue Suede Shoes" was included by the National Recording Preservation Board in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2006.[80]

The Perkins family still owns his songs, the rights to which are administered MPL Communications, a company founded by Paul McCartney.[67]

Drive-By Truckers, on their album The Dirty South, recorded a song about him, "Carl Perkins' Cadillac".

George Thorogood and the Destroyers covered "Dixie Fried" on their 1985 album Maverick. The Kentucky Headhunters also covered the song, as did Keith de Groot on his 1968 album No Introduction Necessary, with Jimmy Page on lead guitar and John Paul Jones on bass.[81]

Ricky Nelson covered Perkins's "Boppin' the Blues" and "Your True Love" on his 1957 debut album, Ricky.

Perkins was portrayed by Johnny Saint Holiday in the 2005 Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line.

Awards

The following recording by Carl Perkins was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, which is a special Grammy award established in 1973 to honor recordings that are at least 25 years old and that have "qualitative or historical significance".

| Carl Perkins: Grammy Hall of Fame Awards[82] | |||||

| Year Released | Title | Genre | Label | Year Inducted | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | "Blue Suede Shoes" | Rock and Roll (single) | Sun Records | 1986 | |

Discography

Studio albums

- Dance Album (1957)

- Whole Lotta Shakin' (1958)

- On Top (1969)

- My Kind of Country (1973)

- Ol' Blue Suede's Back (1978)

- Country Soul (1979)

- Disciple in Blue Suede Shoes (1984)

- Born to Rock (1989)

Collaborative albums

- Boppin' the Blues (1970, with NRBQ)

- The Survivors (1982, with Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash)

- Class of '55 (1986, with Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash)

- The Million Dollar Quartet (1990, with Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash)

- 706 Re-Union (1990, with Scotty Moore)

- Carl Perkins & Sons (1993, with his sons Greg and Stan)

- Go Cat Go! (1996, with various guest stars)

Live albums

- The Carl Perkins Show (1976)

- Live at Austin City Limits (1981)

- The Silver Eagle Cross Country: Carl Perkins Live (1997)

- Live (2000)

Religious albums

- Cane Creek Glory Church (1979)

- Gospel (1984)

Selected compilations

- Country Boy Dreams (1967)

- Carl Perkins' Greatest Hits (1969, re-recordings)

- Original Golden Hits (1969)

- That Rockin' Guitar Man (1981)

- Presenting Carl Perkins (1982)

- Boppin' the New Bleus (1982)

- Born to Boogie (1982)

- The Heart and Soul of Carl Perkins (1983)

- Carl Perkins (1985)

- Original Sun Greatest Hits (1986)

- Up Through the Years 1954–57 (1986)

- Friends, Family & Legends (1992)

Guest appearances

- Judds: Greatest Hits Volume II (1991)

- Philip Claypool: Perfect World (1999)

Charted albums

| Year | Album | Peak positions | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Country | |||

| 1969 | Carl Perkins' Greatest Hits (re-recordings) | 32 | Columbia |

| On Top | 42 | ||

| Original Golden Hits | 43 | Sun | |

| 1973 | My Kind of Country | 48 | Mercury |

| 1982 | The Survivors Live (with Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis) |

21 | Columbia |

| 1986 | Class of '55 (with Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison and Johnny Cash) |

15 | America/Mercury |

Charted singles

| Year | Single | Peak chart positions | Album | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Country | US | CAN Country | |||

| 1956 | "Blue Suede Shoes" | 1 | 2 | — | Dance Album of ... Carl Perkins |

| "Boppin' the Blues" | 7 | 70 | — | ||

| "Dixie Fried" | 10 | — | — | Original Golden Hits | |

| "I'm Sorry, I'm Not Sorry" | flip | — | — | Blue Suede Shoes | |

| 1957 | "Your True Love" | 13 | 67 | — | Dance Album of ... Carl Perkins |

| 1958 | "Pink Pedal Pushers" | 17 | 91 | — | The King of Rock |

| 1959 | "Pointed Toe Shoes" | — | 93 | — | |

| 1966 | "Country Boy's Dream" | 22 | — | — | Country Boy's Dream |

| 1967 | "Shine, Shine, Shine" | 40 | — | — | |

| 1969 | "Restless" | 20 | — | — | Carl Perkins' Greatest Hits |

| 1971 | "Me Without You" | 65 | — | — | The Man Behind Johnny Cash |

| "Cotton Top" | 53 | — | — | ||

| 1972 | "High on Love" | 60 | — | — | Single only |

| 1973 | "(Let's Get) Dixiefried" (1973 version) | 61 | — | — | My Kind of Country |

| 1986 | "Birth of Rock and Roll" | 31 | — | 44 | Class of '55 |

| 1987 | "Class of '55" | 83 | — | — | |

| 1989 | "Charlene" | — | — | 74 | Born to Rock |

Notes

- 1 2 3 Pareles.

- 1 2 Naylor, p. 118.

- ↑ "Rock 'n Roll Legend Carl Perkins' Much Anticipated Story to Come to the Big Screen". August 16, 2007. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Archived February 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 Carl Perkins interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Naylor.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 21.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 30, 55.

- ↑ Archived April 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 30, 68.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 36–41.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 48.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 32, 70–71.

- ↑ "The Legend Carl Perkins". Rockabillytennessee.com. 1998-01-19. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 77.

- 1 2 The Atlantic. December 1970. p. 100. "The Top Beats the Bottom: Carl Perkins and his Music".

- ↑

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 79–90.

- ↑ Rockabilly Legends. Naler. page 121.

- ↑ VanHecke, Susan (2000). Race with the Devil. St. Martin's Press. p. 219. ISBN 0-312-26222-1.

- ↑

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 106–108.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 122–124.

- ↑

- ↑ "MP3 recording" (MP3). Rcs-discography.com. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- 1 2 3

- ↑ Billboard October 22, 1955. Reviews of New C&W Records. p. 44.

- ↑ "MP3 recording" (MP3). Rcs-discography.com. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ↑ Good Rockin' Tonight: Sun Records and the Birth of Rock 'n' Roll, by Colin Escott, Martin Hawkins. Google eBook retrieved 10.11.2011

- ↑ Go, Cat, Go! by Carl Perkins and David McGee 1996 p.129 Hyperion Press ISBN 0-7868-6073-1

- 1 2 Miller, James (1999) Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947–1977. Simon & Schuster (124–25). ISBN 0-684-80873-0.

- ↑ Naylor, p. 135.

- 1 2 Naylor, p. 137.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 178, 180.

- ↑ The Blue Moon Boys - The Story of Elvis Presley's Band. Ken Burke and Dan Griffin. 2006. Chicago Review Press. p. 88. ISBN 1-55652-614-8

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 182, 184.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 173.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 187.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 184.

- ↑ "Elvis's Television Appearances 1956–1973". Kki.pl. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Top 20 Billboard Singles: Billboard Chart Statistics: All About Elvis". Elvis.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 191.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 198.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 188, 210, 212.

- ↑ Billboard September 29, 1956. pages 73, 78.

- ↑ Archived February 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Town Hall Party". hillbilly-music.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "Tour Information 1964". Chuckberry.de. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Naylor, p. 142.

- ↑ The Beatles "Glad All Over". "The Beatles Lyrics - Glad All Over". Oldielyrics.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Carl Perkins - Big Bad Blues / Lonely Heart - Brunswick - UK - 05909". 45cat. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ↑ Perkins, pp. 309–310.

- ↑ "Restless - Carl Perkins". Rockabillyeurope.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Kraft Music Hall: Johnny Cash ... On The Road Episode Summary". TV.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "The Johnny Cash Show Season 2 Episode Guide". TV.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Perkins.

- ↑ "RAB Hall of Fame: Carl Perkins". Rockabilly Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ "On Top - Carl Perkins". AOL Music. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Boppin' the Blues Columbia CS9981 1969

- 1 2 Mike Kovacich (April 17, 2003). "MACCA-News: McCartney To Administer Perkins's music". Macca-central.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Tug Of War". Jpgr.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Naylor, p. 145.

- ↑ DVD Carl Perkins & Friends. Released by Graham Nolder/Snapper Music. 2006. Cat:SDVD514

- ↑ "Into the Night (1985) : Full Cast & Crew". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ↑ "Carl Perkins/Various Artists: Go Cat Go!". Theband.hiof.no. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑

- ↑ Tennessee Historial Commission

- ↑ "Pentatonics" (PDF). Paul-clark.com. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ↑ Perkins, p. 78.

- ↑ "The Carl Perkins Story". Billboardpublicitywire.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Rock 'N Roll Legend Carl Perkins's Much Anticipated Story To Come To The Big Screen". Billboard Publicity Wire.

- ↑ "The Immortals: The First Fifty". Rolling Stone (946).

- ↑ "2006 National Recording Registry choices". Loc.gov. 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "George Thorogood & The Destroyers Albums". Softshoe-slim.com. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Grammy Hall Of Fame". Grammy.org. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

References

- Guterman, Jimmy. (1998.) "Carl Perkins". The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, ed. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 412–413.

- Naylor, Jerry; Halliday, Steve. The Rockabilly Legends: They Called It Rockabilly Long Before They Called It Rock and Roll. Milwaukee, Wisc.: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-2042-2. OCLC 71812792.

- Pareles, Jon (January 20, 1998). "Carl Perkins Dies at 65; Rockabilly Pioneer Wrote 'Blue Suede Shoes'". New York Times. p. B12. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Perkins, Carl; McGee, David (1996). Go, Cat, Go!. New York: Hyperion Press. ISBN 0-7868-6073-1. OCLC 32895064..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Perkins. |

- The Carl Perkins Story at the Internet Movie Database

- Carl Perkins biography

- Perkins' page at the Rockabilly Hall of Fame

- Carl Perkins bio at Rolling Stone

- Carl Perkins Biography at The History of Rock