Canavan disease

| Canavan disease | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E75.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 330.0 |

| OMIM | 271900 |

| DiseasesDB | 29780 |

| MedlinePlus | 001586 |

| MeSH | D017825 |

Canavan disease, also called Canavan–van Bogaert–Bertrand disease, is an autosomal recessive[1] degenerative disorder that causes progressive damage to nerve cells in the brain, and is one of the most common degenerative cerebral diseases of infancy. It is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme aminoacylase 2,[2] and is one of a group of genetic diseases referred to as a leukodystrophies. It is characterized by degeneration of myelin in the phospholipid layer insulating the axon of a neuron and is associated with a gene located on human chromosome 17.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Canavan disease, which appear in early infancy and progress rapidly, may include intellectual disability, loss of previously acquired motor skills, feeding difficulties, abnormal muscle tone (i.e., floppiness or stiffness), poor head control, and megalocephaly (abnormally enlarged head). Paralysis, blindness, or seizures may also occur.

Pathophysiology

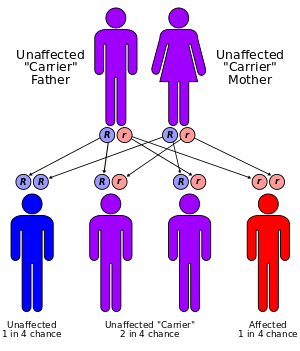

Canavan disease is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. When both parents are carriers, there is a 25% chance of having an affected child. Genetic counseling and genetic testing is recommended for families with two parental carriers.

Canavan disease is caused by a defective ASPA gene which is responsible for the production of the enzyme aspartoacylase. Decreased aspartoacylase activity prevents the normal breakdown of N-acetyl aspartate, wherein the accumulation of N-acetylaspartate, or lack of its further metabolism interferes with growth of the myelin sheath of the nerve fibers of the brain. The myelin sheath is the fatty covering that surrounds nerve cells and acts as an insulator, which allows for efficient transmission of nerve impulses.

Treatment

There is no cure for Canavan disease, nor is there a standard course of treatment. Treatment is symptomatic and supportive. There is also an experimental treatment using lithium citrate. When a person has Canavan disease, his or her levels of N-acetyl aspartate are chronically elevated. The lithium citrate has proven in a rat genetic model of Canavan disease to be able to significantly decrease levels of N-acetyl aspartate. When tested on a human, the subject reversed during a two-week wash-out period after withdrawal of lithium.

The investigation revealed both decreased N-acetyl aspartate levels in regions of the brain tested and magnetic resonance spectroscopic values that are more characteristic of normal development and myelination. This evidence suggests that a larger controlled trial of lithium may be warranted as supportive therapy for children with Canavan disease.[3]

In addition there are experimental trials of gene therapy, published in 2002, involving using a healthy gene to take over for the defective one that causes Canavan disease.[4] In human trials, the results of which were published in 2012, this method appeared to improve the life of the patient without long-term adverse effects during a 5-year follow-up.[5]

Prognosis

Death usually occurs before age ten,[6] but some children with milder forms of the disease survive into their teens and twenties.

Prevalence

Although Canavan disease may occur in any ethnic group, it affects people of Eastern European Jewish ancestry more frequently. About 1 in 40 (2.5%) individuals of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish ancestry are carriers.

Research

Research involving triacetin supplementation has shown promise in a rat model.[7] Triacetin, which can be enzymatically cleaved to form acetate, enters the brain more readily than the negatively charged acetate. The defective enzyme in Canavan disease, aspartoacylase, converts N-acetylaspartate into aspartate and acetate. Mutations in the gene for aspartoacylase prevent the breakdown of N-acetylaspartate, and reduce brain acetate availability during brain development. Acetate supplementation using Triacetin is meant to provide the missing acetate so that brain development can continue normally.

A team of researchers headed by Paola Leone are currently at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, in Stratford, New Jersey. The brain gene therapy is conducted at Cooper University Hospital. The procedure involves the insertion of six (6) catheters into the brain that deliver a solution containing 600 billion to 900 billion engineered virus particles. The virus, a modified version of AAV, is designed to replace the aspartoacylase enzyme.[4] Children treated with this procedure to date have shown marked improvements, including the growth of myelin with decreased levels of the n-acetyl-aspartate toxin.[8]

Patient Reported Outcomes

The Canavan Disease Research foundation promotes a patient registry to collect information directly from the patient community. Below is an infographic providing a snapshot of the engaged patients in the community and how they are living with Canavan disease.

History

Canavan disease was first described in 1931 by Myrtelle Canavan.[9]

Greenberg v. Miami Children's Hospital Research Institute

The discovery of the gene for Canavan disease, and subsequent events, generated considerable controversy. In 1987 the Greenbergs, a family with two children affected by Canavan disease, donated tissue samples to Reuben Matalon, a researcher at the University of Chicago who was looking for the Canavan gene. He successfully identified the gene in 1993 and developed a test for it that would enable antenatal (before birth) counseling of couples at risk of having a child with the disease.[10] For a while, the Canavan Foundation offered free genetic testing with the test.

However, in 1997, after relocating to Florida, Matalon's employer, Miami Children's Hospital, patented the gene and started claiming royalties on the genetic test, forcing the Canavan Foundation to withdraw their testing. A subsequent lawsuit brought by the Canavan Foundation against Miami Children's Hospital, and was resolved with a sealed out-of-court settlement.[11] The case is sometimes cited in arguments about the appropriateness of patenting genes.

See also

- The Myelin Project

- The Stennis Foundation

- Fern Kupfer whose book Before and After Zachariah is an account of raising a child with Canavan disease

References

- ↑ Namboodiri, Am; Peethambaran, A; Mathew, R; Sambhu, Pa; Hershfield, J; Moffett, Jr; Madhavarao, Cn (June 2006). "Canavan disease and the role of N-acetylaspartate in myelin synthesis". Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 252 (1–2): 216–23. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.016. PMID 16647192.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 271900

- ↑ Assadi, M.; Janson, C.; Wang, D. J.; Goldfarb, O.; Suri, N.; Bilaniuk, L.; Leone, P. (Jul 2010). "Lithium citrate reduces excessive intra-cerebral N-acetyl aspartate in Canavan disease". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 14 (4): 354–359. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.11.006. PMID 20034825.

- 1 2 Janson, Christopher; McPhee, Scott; Bilaniuk, Larissa; Haselgrove, John; Testaiuti, Mark; Freese, Andrew; Wang, Dah-Jyuu; Shera, David; Hurh, Peter; Rupin, Joan; Saslow, Elizabeth; Goldfarb, Olga; Goldberg, Michael; Larijani, Ghassem; Sharrar, William; Liouterman, Larisa; Camp, Angelique; Kolodny, Edwin; Samulski, Jude; Leone, Paola (20 July 2002). "Gene Therapy of Canavan Disease: AAV-2 Vector for Neurosurgical Delivery of Aspartoacylase Gene ( ) to the Human Brain". Human Gene Therapy. 13 (11): 1391–1412. doi:10.1089/104303402760128612. PMID 12162821.

- ↑ Leone, P.; Shera, D.; McPhee, S. W. J.; Francis, J. S.; Kolodny, E. H.; Bilaniuk, L. T.; Wang, D.-J.; Assadi, M.; Goldfarb, O.; Goldman, H. W.; Freese, A.; Young, D.; During, M. J.; Samulski, R. J.; Janson, C. G. (19 December 2012). "Long-Term Follow-Up After Gene Therapy for Canavan Disease". Science Translational Medicine. 4 (165): 165ra163–165ra163. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003454. PMID 23253610.

- ↑ NIH.gov: Canavan disease

- ↑ Mathew R, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, Moffett JR, Namboodiri MA (2010). "Metabolic acetate therapy improves phenotype in the tremor rat model of Canavan disease.". J. J Inherit Metab Dis. 33 (3): 195–210. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9100-z. PMC 2877317

. PMID 20464498.

. PMID 20464498. - ↑ "Our Story: The Search for a Cure". Canavan Research Foundation. Retrieved Nov 22, 2010.

- ↑ Matalon, R (1997). "Canavan disease: diagnosis and molecular analysis.". Genetic testing. 1 (1): 21–5. PMID 10464621.

- ↑ Colaianni, A; Chandrasekharan, S; Cook-Deegan, R (April 2010). "Impact of gene patents and licensing practices on access to genetic testing and carrier screening for Tay-Sachs and Canavan disease.". Genetics in Medicine. 12 (4 Suppl): S5–S14. doi:10.1097/gim.0b013e3181d5a669. PMC 3042321

. PMID 20393311.

. PMID 20393311.

External links

- Information on the disorder from the National Institute of Neurological Disorder and Stroke

- Cell & Gene Therapy Center at UMDNJ

- Canavan Research Illinois - A public charity devoted to curing Canavan disease

- Canavan Research - A foundation devoted to curing Canavan disease

- GeneReviews/NCBI/UW/NIH entry on Canavan disease

- Jacob's Cure - A foundation dedicated to curing Canavan disease

- The Canavan Foundation - offering information, support, testing, and sponsoring research into Canavan disease