Camelops

| Camelops Temporal range: Late Pliocene to Early Holocene, 2.5–0.010 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

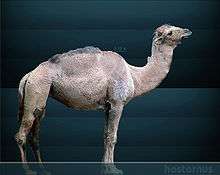

| Mounted skeleton of Camelops hesternus in the George C. Page Museum, Los Angeles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Tribe: | Camelini |

| Genus: | †Camelops Leidy, 1854 |

| Species | |

|

†Camelops kansanus Leidy, 1854

†Camelops hesternus Leidy, 1873 (type) | |

Camelops is an extinct genus of camel that once roamed western North America, where it disappeared at the end of the Pleistocene about 10,000 years ago. It was very closely related to the Old World Dromedary and Bactrian Camel in anatomical form. Its name is derived from the Greek κάμελος (camel) + ὀψ (face), thus "camel-face."

Evolution

The genus Camelops first appeared during the Late Pliocene period and became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. Despite the fact that camels are presently associated with the deserts of Asia and Africa, the family Camelidae, which comprises camels and llamas, originated in North America during the middle Eocene period, at least 44 million years ago.[1] The camel and horse families originated in the Americas and migrated into Asia via the Bering Strait.[2] The skull of a Camelops was found above the Glenns Ferry Formation, in a thick layer of coarse gravel known as the Tauna Gravels. Above this layer of gravel is another layer of fine river channel sands, where the skull was found. This indicates that the Camelops is perhaps as young as 2 million years old, and perhaps even younger. This can be inferred because it is younger than the other fossils found at the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument.[3]

During the late Oligocene and early Miocene periods, camels underwent swift evolutionary change, resulting in several genera with different anatomical structures, ranging from those with short limbs, those with gazelle-like bodies, and giraffe-like camels with long legs and long necks. This rich diversity decreased until only a few species, such as Camelops hesternus, remained in North America, before going extinct entirely around 11,000 years ago.[1] Camelops' extinction was part of a larger North American die-off in which native horses, camelids and mastodons also died out. Possibilities for extinction include global climate change and hunting pressure from the arrival of the Clovis people, who were prolific hunters with distinct fluted stone tools which allowed for a spear to be attached to the stone tool.[1][2] This megafaunal extinction coincided roughly with the appearance of the big game hunting Clovis culture, and biochemical analyses have shown that Clovis tools were used in butchering camels.[4]

Description

Because soft tissues are generally not preserved in the fossil record, it is not certain if Camelops possessed a hump, like modern camels, or lacked one, like its modern llama relatives. Camelops hesternus was 2.2 m (7.2 ft) tall at the shoulder, making it slightly taller than modern Bactrian camels. It was slightly heavier also, weighing about 800 kg (1,800 lb).[5]

Palaeobiology

Plant remains found in its teeth exhibit little grass, suggesting that the camel was an opportunistic herbivore; that is, it ate any plants that were available, as do modern camels. Studies on the Rancho La Brea Camelops hesternus fossils further reveal that rather than being limited to grazing, this species likely ate mixed species of plants, including coarse shrubs growing in coastal southern California. Camelops probably could travel long distances, similar to the living camel. The ability to exist for long periods without water, such as modern-day camels, is still unknown; this may have been an adaptation that occurred much later, after camelids migrated to Asia and Africa.[6]

Extinction

The last species of Camelops are hypothesized to have disappeared as a result of the Blitzkrieg model. This model presents the hypothesis that Camelops, along with other North American megafauna, disappeared as the result of North American hunters moving southeastward. The result of movement of humans and the growth of the human population was the reduction in prey ranges for the megafauna.[7] Of the many Camelops specimens recovered in North America, mostly in the Wisconsin region, only a small number demonstrate modification through human actions.[8] However some have been interpreted as having been killed by humans based on spirally fractured bone fragments. None of the reported Camelops sites have been associated with stone tools, which would be an indicator of possibly human utilization.[8]

At many of these Camelops sites, there were no fossils of carcasses that were evidently processed, but rather small fragments and pieces of remains. Researchers originally thought that Camelops were in fact hunted and butchered by early humans in North America because of the following four reasons: the fragmenting of bones into shapes that look like tools, damage or weathering of the “working” edge of said tools, having attributes that were similar to the making of chopping tools, and scarred fragments from possible chopping tools.[8] Further examination showed however that these assumptions were misguided, and that while humans did coexist and associate with Camelops, human utilization has yet to be completely proven as the sole cause of extinction.[8]

Walmart camel

The "Walmart camel" is the fossil of a prehistoric mammal, originally thought to be a camel, found at a Walmart construction site in Mesa, Arizona in 2007. Workers digging a hole for an ornamental citrus tree found the bones of two (juvenile and infant) animals that may have lived about 10,000 years ago.[9] Arizona State University Geology Museum curator Brad Archer called it an important and rare find for the area.[10] Walmart officials and Greenfield Citrus Nursery owner John Babiarz whose crew discovered the remains agreed that the bones would go directly to the Geology Museum at Arizona State University where further research and restoration of the fossils could be done. Further studies of the fossil remains proved inconclusive as to their identity as several diagnostic elements of the skeleton were not preserved or were removed from the site during previous excavations in the same area. Other fossils, positively identified as camel bones, were found in Gilbert, Arizona in May 2008.[11][12]

See also

- Aepycamelus

- Oxydactylus

- Pleistocene megafauna

- Poebrotherium

- Procamelus

- Protylopus

- Snowmastodon Project

- Stenomylus

- Syrian camel, an extinct species that reached at least 9 feet (2.7 m) tall at the shoulder

References

- 1 2 3 "Camelops". Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Paleontology Society.

- 1 2 Hutchinson, Jon (2012-08-14). "Camel Country: Where have all our camelops gone?". Verde Independnet.

- ↑ National Park Service. "Camelops". Hagerman Fossil Beds. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- ↑ Scott, J. (2009-02-26). "Camel-butchering in Boulder, 13,000 years ago". Colorado Arts and Sciences Magazine. University of Colorado at Boulder. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑

- ↑ "Western Camel (Extinct) Camelops hesternus"

- ↑ "On Discerning the Cause of Late Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinctions"

- 1 2 3 4 Haynes, Gary; Stanford, Dennis (September 1984). "On the possible utilization of Camelops by early man in North America" (PDF). Quaternary Research. 22 (2): 216–230. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(84)90041-3.

- ↑ Richardson, Christian (April 28, 2007). "Prehistoric camel bones found in Mesa". East Valley Tribune. Archived from the original on 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Associated Press. "10,000-year-old camel bones found in Arizona". MSN. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ↑ Markham, Chris (May 25, 2008). "Rare camel fossil unearthed in southeast Gilbert". East Valley Tribune.

- ↑ Bones of large prehistoric camel found in Gilbert, The Arizona Republic, May 21, 2008