Brennan torpedo

| Brennan torpedo | |

|---|---|

|

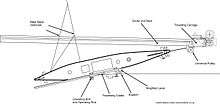

Brennan torpedo replica at the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence; cut-out shows the two drums of wire used for propulsion and guidance | |

| Type | Torpedo |

| Place of origin |

|

| Service history | |

| In service | 1890-1906 |

| Used by |

|

| Production history | |

| Designer | Louis Brennan |

| Designed | 1874-1877 |

| Manufacturer | Brennan Torpedo Company |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 15 feet (4.6 m)[1] |

|

| |

| Effective firing range | 2,000 yards (1,800 m) |

| Warhead weight | 200 pounds (91 kg)[2] |

|

| |

| Engine | Shore-based steam winch |

| Maximum depth | 12 feet (3.7 m) |

| Speed | 27 knots (14 m/s) |

Guidance system | Wire |

Launch platform | Shore-based harbor defense installations |

The Brennan torpedo was a torpedo patented by Irish-born Australian inventor Louis Brennan in 1877. It was propelled by two contra-rotating propellors that were spun by rapidly pulling out wires from drums wound inside the torpedo. Differential speed on the wires connected to the shore station allowed the torpedo to be guided to its target, up to 2,000 yards (1,800 m) away, at speeds of up to 27 knots (31 mph).

The Brennan torpedo is often claimed as the world's first guided missile, but guided torpedoes invented by John Ericsson, John Louis Lay, and Victor von Scheliha all predate it; however, Brennan's torpedo was much simpler in its concept and worked over an acceptable range at a satisfactory speed so it might be more accurate to call it "the world's first practical guided missile".[3]

Description

The Brennan torpedo was similar in appearance to more modern ones, apart from having a flattened oval cross-section instead of a circular one. It was designed to run at a consistent depth of 12 feet (3.7 m), and was fitted with an indicator mast that just broke the surface of the water; at night the mast had a small light fitted which was only visible from the rear.

Two steel drums were mounted one behind the other inside the torpedo, each carrying several thousands yards of high-tensile steel wire. The drums were connected via a differential gear to twin contra-rotating propellers. If one drum was rotated faster than the other, then the rudder was activated. The other ends of the wires were connected to steam-powered winding engines, which were arranged so that speeds could be varied within fine limits, giving sensitive steering control for the torpedo.

The torpedo attained a speed of 20 knots (23 mph) using a wire .04 inches (1.0 mm) in diameter but later this was changed to .07 inches (1.8 mm) to increase the speed to 27 knots (31 mph). The torpedo was fitted with elevators controlled by a depth-keeping mechanism, and the fore and aft rudders operated by the differential between the drums.

In operation, the torpedo's operator would be positioned on a 40 feet (12 m) high telescopic steel tower, which could be extended hydraulically. He was provided with a special pair of binoculars on which were mounted controls which could be used to electrically control the relative speeds of the twin winding engines. In this way he was able to follow the track of the torpedo and steer it with a great degree of accuracy. In tests carried out by the Admiralty the operator was able to hit a floating object at 2,000 yards (1,800 m) and was able to turn the torpedo through 180 degrees to hit a target from the off side.

History

Tomlinson on page 12 states that in 1874 while watching a planing machine worked by a driving belt, Brennan stumbled on the paradox that it was possible to make a machine travel forward by pulling it backward.

Beanse on page 2 expands Brennan’s observation of the driving belt powering the planing machine was taut and the non-driving side was slack. Brennan reasoned that if one dispensed with the non-driving side it would be possible to transfer energy to a vehicle and power it from a static power source. The concept was to place a drum of fine wire in the vehicle in place of the belt. The wire was attached to an engine to wind it in, rotating the drum that then propelled the vehicle away from its start point.

Gillingham Public Libraries on page 4 refers to the Daily Mail report of Brennan’s death on 17th January 1932 … He demonstrated this by means of a cotton reel, with a pencil thrust through the hole in the centre. By resting the ends of this pencil on two books and unwinding the cotton by pulling it from underneath he caused the reel to roll forward, the harder he pulled the faster the cotton unwound and the quicker the reel travelled in the reverse direction.

Brennan began making rough sketches of such a torpedo, and as the concept developed he sought the mathematical assistance of William Charles Kernot, a lecturer at Melbourne University.[3]

After earlier experiments with a single propeller, by 1878 Brennan had produced a working version about 15 feet (4.6 m) long, made from iron boiler plate, with twin contra-rotating propellers. Tests carried out in the Graving Dock at Williamstown, Victoria were successful, with steering proving to be reasonably controllable, although depth-keeping was not.

The British Admiralty had meanwhile instructed Rear Admiral J. Wilson, the Commodore of the Royal Navy's Australian Squadron, to investigate the weapon and report back. Alexander Kennedy Smith was also working to obtain the Victoria government's backing for the project and raised the subject in the state's legislature on 2 October 1877. A grant was eventually awarded for the development of the torpedo, and in March 1879 it was successfully tested in Hobsons Bay, Melbourne.

Brennan had by now established the Brennan Torpedo Company, and had assigned half of the rights on his patent to civil engineer John Ridley Temperley, in exchange for much-needed funds. Brennan and Temperley soon afterwards travelled to Britain, where the Admiralty examined the torpedo and found it unsuitable for shipboard use. However, the War Office proved more amenable, and in early August 1881 a special Royal Engineer committee was instructed to inspect the torpedo at Chatham and report back directly to the Secretary of State for War, Hugh Childers. The report strongly recommended that an improved model be built at government expense. At the time the Royal Engineers - part of the Army - were responsible for Britain's shore defenses, while the Royal Navy were responsible for its seaward protection.

In 1883 an agreement was reached between the Brennan Torpedo Company and the government. The newly appointed Inspector-General of Fortifications in England, Sir Andrew Clarke, appreciated the value of the torpedo and in spring 1883 an experimental station was established at Garrison Point Fort, Sheerness on the River Medway and a workshop for Brennan was set up at the Chatham Barracks, the home of the Royal Engineers. Between 1883 and 1885 the Royal Engineers held trials and in 1886 the torpedo was recommended for adoption as a harbour defence torpedo.

In 1884 Brennan received a letter from the War Office stating that they had decided to adopt his torpedo for harbour defence and he was invited to attend a meeting to decide the value of his invention. Brennan decided to accept £40,000 as a quick answer to his financial worries but his business partner J.R. Temperley assumed control of the negotiations and demanded £100,000. The War Office agreed to this, but said that it would have to be paid out over a period of three years. Brennan accepted this, but Temperley demanded a further £10,000 for the delay, and after some argument the War Office agreed, also agreeing to pay Brennan a sizable salary to act as production chief. A scandal eventually blew up over this sum, which was wildly extravagant in comparison to the £15,000 paid for manufacturing rights to the Whitehead torpedo only 15 years previous.

The Brennan torpedo became a standard harbour defence throughout the British Empire and was in use for more than fifteen years. Operational stations were established in the UK at Cliffe Fort, Fort Albert on the Isle of Wight and Plymouth. Other stations included Fort Camden in Cork Harbour, Ireland, Lei Yue Mun Fort in Hong Kong and Forts Ricasoli and Tigné in Malta.

In 1905 the Committee on Armaments of Home Ports issued a report in which they recommended the removal of all Brennan torpedoes from fixed defences due to their comparatively short range and the difficulty of launching them at night. Manufacture of the Brennan torpedo finished in 1906.

Installations

In 1891 It was intended to build fifteen stations as indicated in a report to the Director of Artillery.[4] We have now completed or in progress 7 installations viz. Thames (Cliffe), Medway (Garrison Pt), Portsmouth (Cliff End/Fort Albert), Plymouth (Pier Cellars/Cawsand Bay), Cork Harbour (Fort Camden), Malta (Tigné and Ricasoli). Further sites proposed as funds become available at Plymouth (Bovisand), Milford Haven, Clyde, Forth, Falmouth, Hong Kong, Singapore and St Lucia. The first seven were completed but out of the other eight only the one at Lye Mun was completed. The plans for two installations at Dale Point and Great Castle Head, Milford Haven were drawn up but not carried out.[5] Four Brennan installations were added to existing fotrifications at Fort Albert on the Isle of Wight, Cliffe Fort on the Thames, Garrison Point at the entrance to The Medway and at Fort Ricasoli at the entrance to the Grand Harbour at Malta. With the exception of Ricasoli, the design of these was constrained by the existing structure and resulted in unique designs. In addition the ones at Fort Camden at Cork and Tigné at Malta together with proposed designs for Milford Haven followed a very similar layout while the Installations at Lye Mun in Hong Kong and Pier Cellars at Plymouth were individual designs.

Installation remains

The installation at Fort Albert has been completely destroyed. That at Cliffe Fort partially exists, including a slipway and parts of a telescopic control tower. Parts of the installation at Garrison Point survive including the direction stations on the face of the fort and parts of the slipway supports. The complete installation at Pier Cellars still exists although it was greatly modified during later use for midget submarines. At Malta the Tigne installation was later converted for use as the boom defence station but the rooms still exist. At Fort Ricasoli the complex of buildings still exist and the slipway is mostly intact. At Lye Mun the installation has been incorporated into a museum with a replica Brennan Torpedo on display. At Fort Camden most of the installation still exists but is derelict.

Surviving examples

The only remaining original Brennan Torpedo is exhibited at the Royal Engineers Museum in Chatham, Kent. However, traces of the installation at Fort Camden in County Cork are visible to this day. There is also a display at Lei Yue Mun Fort in Hong Kong which shows a replica Brennan Torpedo with the side cut away so the workings are visible.

Notes

- ↑ Gray, Edwyn (2004). Nineteenth Century Torpedoes and Their Inventors. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-341-1.

- ↑ "Brief History of the Torpedo". Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- 1 2 Gray, Edwyn (2004). Nineteenth-Century Torpedoes and Their Inventors. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-341-1.

- ↑ National Archive in WO32/6064 In minute to Director of Artillery from Inspector General of Fortifications.

- ↑ The Brennan Torpedo by Alec Beanse p28 EAN 978-0-9548453-6-0

Beanse, Alec (1997). The Brennan Torpedo: The history and operation of the World’s first practicable guided weapon. The Palmerston Forts Society, Fort Nelson, Fareham, Hampshire. 64pp. ISBN 0 9523634 4 5

Gillingham Public Libraries Local History Series No. 5, part 1 (1973). Louis Brennan CB: Dirigible torpedo. 22pp. Louis Brennan CB Exhibition, 12-26 May 1973.

Tomlinson, Norman (1980). Louis Brennan: Inventor extraordinaire. John Hallewell Publications, Chatham, Kent. 105pp. IS BN 0 905540 18 2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brennan Torpedo. |

- Victorian Forts - Brennan Torpedo.

- Brennan Torpedo 1887 - animation showing mechanism and use.