Blindness and education

The subject of blindness and education has included evolving approaches and public perceptions of how best to address the special needs of blind students. The practice of institutionalizing the blind in asylums has a history extending back over a thousand years, but it was not until the 18th century that authorities created schools for them where blind children, particularly those more privileged, were usually educated in such specialized settings. These institutions provided simple vocational and adaptive training, as well as grounding in academic subjects offered through alternative formats. Literature, for example, was being made available to blind students by way of embossed Roman letters.

Ancient Egypt

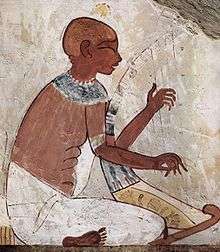

The Ancient Egyptians were the first civilisation to display an interest in the causes and cures for disabilities and during some periods blind people are recorded as representing a substantial portion of the poets and musicians in society.[3] In the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040-1640 BCE) blind harpists are depicted on tomb walls.[1] They were not exclusively interested in the causes and cures for blindness but also the social care of the individual.[2]

Early institutions for the blind

Asylums for the Industrious Blind were established in Edinburgh and Bristol in 1765, but the first school anywhere, to expressly teach the blind was set up by Henry Dannett in Liverpool as the School for the Instruction of the Indigent Blind. It taught the blind children skills in manual crafts although there was no formal education as such. Other institutions set up at that time were: the School for the Indigent Blind in London and the Asylum and School for the Indigent Blind at Norwich.

In France, the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles was established in 1784 by Valentin Haüy. Haüy's impulse to help the blind began when he witnessed the blind being mocked during a religious street festival.[4] In May 1784, at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, he met a young beggar, François Lesueur; he was his first student. He developed a method of raised letters, to teach Lesueur to read, and compose sentences. He made rapid progress, and Haüy announced the success, in September 1784 in the Journal de Paris, then receiving encouragement from the French Academy of Sciences.

With the help of the Philanthropic Society Haüy founded the Institute for Blind Youth, the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles, in February 1785. Building on the philanthropic spinning workshop for the blind, the institution of Blind Children was dedicated on 26 December 1786. Its purpose was to educate students and teach them manual work: spinning, and letterpress.

Attempts to actually educate the blind were first attempted towards the end of the century. Until that time they were considered mostly ineducable and un-trainable. One of the major figures in the movement to educate the blind was Sébastien Guillié. He established the first ophthalmological clinic in France and became director of the school in Paris.

Braille system

Louis Braille attended Haüy's school in 1819 and later taught there. He soon became determined to fashion a system of reading and writing that could bridge the critical gap in communication between the sighted and the blind. In his own words: "Access to communication in the widest sense is access to knowledge, and that is vitally important for us if we [the blind] are not to go on being despised or patronized by condescending sighted people. We do not need pity, nor do we need to be reminded we are vulnerable. We must be treated as equals – and communication is the way this can be brought about."[5]

In 1821, Braille learned of a communication system devised by Captain Charles Barbier of the French Army.[6][7][8] Barbier's "night writing", was a code of dots and dashes impressed into thick paper. These impressions could be interpreted entirely by the fingers, letting soldiers share information on the battlefield without having light or needing to speak.[9]

The captain's code turned out to be too complex to use in its original military form, but it inspired Braille to develop a system of his own.[10][11] Braille worked tirelessly on his ideas, and his system was largely completed by 1824, when he was just fifteen years of age.[5][12] From Barbier's night writing, he innovated by simplifying its form and maximizing its efficiency. He made uniform columns for each letter, and he reduced the twelve raised dots to six. He published his system in 1829, and by the second edition in 1837 had discarded the dashes because they were too difficult to read. Crucially, Braille's smaller cells were capable of being recognized as letters with a single touch of a finger.[12]

Education for the blind

The first school with a focus on proper education was the Yorkshire School for the Blind in England. Established in 1835, it taught arithmetic, reading and writing, while at the school of the London Society for Teaching the Blind to Read founded in 1838 a general education was seen as the ideal that would contribute the most to the prosperity of the blind. Educator Thomas Lucas introduced the Lucas Type, an early form of embossed text different from the Braille system.

Another important institution at the time was the General Institution for the Blind at Birmingham (1847), which included training for industrial jobs alongside a more general curriculum. The first school for blind adults was founded in 1866 at Worcester and was called the College for the Blind Sons of Gentlemen.

In 1889 the Edgerton Commission published a report that recommended that the blind should receive compulsory education from the age of 5–16 years. The law was finally passed in 1893, as an element of the broader Elementary Education Act. This act ensured that blind people up to the age of 16 years were entitled to an Elementary-Level Education as well as to Vocational Training.

The 1880s also saw the introduction of compulsory elementary education for the Blind throughout the United States. (However, most states of the United States did not pass laws specifically making elementary education compulsory for the blind until after 1900.[13])

.jpg)

By this time, reading codes - chiefly Braille and New York Point - had gained favor among educators as embossed letters (such as Moon type were said by some to be difficult to learn and cumbersome to use, and so (DOT CODES) were either newly created or imported from well-established schools in Europe. Though New York Point was widely accepted for a time, Braille has since emerged the victor in what some blindness historians have dubbed “the War of the Dots.”

The more respected residential schools were staffed by competent teachers who kept abreast of the latest developments in educational theory. While some of their methods seem archaic by today’s standards - particularly where their Vocational Training options are concerned - their efforts did pave the way for the education and integration of blind students in the 20th century.

The early 20th century saw a handful of blind students enrolled in their neighborhood schools, with special educational supports. Most still attended residential institutions, but that number dropped steadily as the years wore on - especially after the white cane was adopted into common use as a mobility tool and symbol of blindness in the 1930s.

Today

Most blind and visually impaired students now attend their neighborhood schools, often aided in their educational pursuits by regular teachers of academics and by a team of professionals who train them in alternative skills: Orientation and Mobility (O and M) training - instruction in independent travel - is usually taught by contractors educated in that area, as is Braille.

Blind children may also need special training in understanding spatial concepts, and in self-care, as they are often unable to learn visually and through imitation as other children do. Moreover, home economics and education dealing with anatomy are necessary for children with severe visual impairments.

Since only ten percent of those registered as legally blind have no usable vision, many students are also taught to use their remaining sight to maximum effect, so that some read print (with or without optical aids) and travel without canes.

A combination of necessary training tailored to the unique needs of each student, and solid academics, is going a long way towards producing blind and visually impaired students capable of dealing with the world independently.

See also

- Category:Blindness organizations

- Braille music

- Nico (also known as Nicholas), a TV series for educating children about blind people (considering television a sort of literature)

- Thérèse-Adèle Husson

- T. V. Raman

References

- 1 2 "Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs", James P. Allen, p343, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-77483-7

- 1 2 "The history of special education", Margret A. Winzer", p. 463, Gallaudet University Press, 1993, ISBN 1-56368-018-1

- ↑ "Everybody belongs", Arthur H. Shapiro, p. 152, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0-8153-3960-7

- ↑ Herbermann 1913.

- 1 2 Olmstrom, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Kugelmass (1951), pp. 108–115.

- ↑ Marsan, Colette (2009). "Louis Braille: A Brief Overview". Association Valentin Haüy. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ "Who was Louis Braille?". Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Farrell, p. 96.

- ↑ Kugelmass (1951), pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Farrell, pp. 96–97.

- 1 2 Farrell, p. 98.

- ↑ The Blind: Their Condition and the Work Being Done for Them in the United States, Harry Best, p372, The Macmillan Company, 1919

External links

- Blindness Information Site from the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired

- History of Reading Codes for the Blind

Joseph M. Stadelman (1913). "Education of the Blind". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Dated but useful article on the history

Joseph M. Stadelman (1913). "Education of the Blind". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Dated but useful article on the history-

Thomas E. Finegan (1920). "Education of the Physically Handicapped". Encyclopedia Americana. This article has a section on blind children.

Thomas E. Finegan (1920). "Education of the Physically Handicapped". Encyclopedia Americana. This article has a section on blind children.