Black robin

| Black robin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Petroicidae |

| Genus: | Petroica |

| Species: | P. traversi |

| Binomial name | |

| Petroica traversi (Buller, 1872) | |

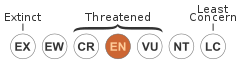

The black robin or Chatham Island robin (Petroica traversi) is an endangered bird from the Chatham Islands off the east coast of New Zealand. It is closely related to the South Island robin (P. australis). It was first described by Walter Buller in 1872.[2] Unlike its mainland counterparts, its flight capacity is somewhat reduced. Evolution in the absence of mammalian predators made it vulnerable to introduced species such as cats and rats, and it became extinct on the main island of the Chatham group before 1871, being restricted to Little Mangere Island thereafter.

Description

The black robin is a small, sparrow-sized bird measuring 10–15 cm (4–6 in). Its plumage is almost entirely brownish-black, with a black bill and brownish-black yellow-soled feet.[3]

Females are usually slightly smaller than males. Male songs are a simple phrase of 5 to 7 notes. Its call is a high pitched single note. Their eyes are dark brown. The birds will moult between December and March.

Ecology and behaviour

Black robins are territorial. Males will patrol and defend their areas. Females have been known to chase away other females. They make short flights from branch to branch and do not fly long distances.

Habitat

Black robins live in low-altitude scrub forest remnants. It is entirely insectivorous, and feeds on the forest floor or on low branches. During breeding, black robins like to nest in hollow trees and tree stumps. They live in woody vegetation, under the canopy of trees - beneath the branches of the akeake trees. To shelter from the strong winds and rough seas around the islands the black robin spends a lot of its time in the lower branches of the forest. They prefer flat areas of the forest with deep litter layers.

Diet

Black robins forage in the leaf litter on the ground for grubs, cockroaches, weta, and worms. Black robins will hunt for food during the day and night and have good night vision.

Reproduction

Black robins will generally start to breed at two years of age. The female robin will make the nest and while she lays and incubates the eggs the male will feed the female for a rest.

Eggs are laid between early October and late December. A second clutch may be laid if the first is unsuccessful. Generally two eggs are laid but it is sometimes just one, or maybe three. Eggs are creamy in colour with purple splotches. When the eggs are laid the female will sit on them to keep them warm until they hatch in about 18 days. Then both parents will help to feed the chicks. Chicks often spend the first day or two, after leaving the nest, on the ground - a dangerous place to be for it with predators that are possibly there. Young robins stay in the nest for about 23 days after hatching, but even after leaving the nest the parents will continue to feed them until they are about 65 days old. This is much longer than other birds of the black robin's size.

Life expectancy

Survivorship between 1980 and 1991 indicates a mean life expectancy of four years. "Old Blue" however, the sole breeding female in 1980, lived for over 14 years. Some can live from 6 to 13 years.

Conservation and distribution

There are now around 250 black robins, but in 1980 only five survived on Little Mangere Island. They were saved from extinction by Don Merton and his Wildlife Service team, and by "Old Blue", the last remaining fertile female. The remaining birds were moved to Mangere Island. The team increased the annual output of Old Blue (and later other females) by removing the first clutch over every year and placing the eggs in the nest of the Chatham race of the tomtit, a technique known as cross-fostering. The tomtits raised the first brood, and the black robins, having lost their eggs, relaid and raised another brood.[4]

Many females laid eggs on the rims of nests where the eggs could not survive without help. Human conservationists pushed the eggs back into the nests where they were incubated and hatched successfully. The maladaptive gene causing this behaviour spread until over 50% of females laid rim eggs. Humans stopped pushing eggs back in time to prevent the gene spreading to all birds which could have made the birds dependent on humans indefinitely. After human intervention stopped rim laying became less frequent, but 9% of birds still laid rim eggs as of 2011. Conservationists have faced some criticism that they may inadvertently do harm if they allow organisms with deleterious traits to survive and perpetuate what is maladaptive.[5]

All of the surviving black robins are descended from "Old Blue", giving little genetic variation among the population and creating an extreme population bottleneck. Interestingly, this seems to have caused no inbreeding problems, leading to speculation that the species has passed through several such population reductions in its evolutionary past and thus losing any alleles that could cause deleterious inbreeding effects. It was generally assumed that the minimum viable population protecting from inbreeding depression was around 50 individuals, but this is now known to be an inexact average, with the actual numbers being below 10 in rapidly reproducing small-island species such as the black robin, to several hundred in long-lived continental species with a wide distribution (such as elephants or tigers).

The species is still endangered, but now numbers around 250 individuals in populations on Mangere Island and South East Island. Ongoing restoration of habitat and eradication of introduced predators is being undertaken so that the population of this and other endangered Chatham endemics can be spread to several populations, decreasing the risk of extinction by natural disasters or similar stochastic events.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2013). "Petroica traversi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ The binomial commemorates the New Zealand botanist Henry H. Travers (1844–1928). The new guide to the birds of New Zealand and outlying islands. Collins, Auckland.

- ↑ Falla, R. A., R. B. Sibson, and E. G. Turbott (1979)

- ↑ Cemmick, David; Dick Veitch (1986). Black Robin Country. Auckland: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-340-35826-9.

- ↑ Massaro, Melanie; Sainudiin, Raazesh; Merton, Don; Briskie, James V.; Poole, Anthony M.; Hale, Marie L. (9 December 2013). "Human-Assisted Spread of a Maladaptive Behavior in a Critically Endangered Bird". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e79066. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079066. PMC 3857173

. PMID 24348992 – via PLoS Journals.

. PMID 24348992 – via PLoS Journals.

- Butler, David; Merton, Don; (1992). The Black Robin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558260-8

External links

- Black robin

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- "Black robin recovery plan 2001-2011" (PDF). Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. 2001. Retrieved 2007-09-19.