Biological therapy for inflammatory bowel disease

Biological therapy refers to the use of medication that is tailored to specifically target an immune or genetic mediator of disease.[1] Even for diseases of unknown cause, molecules that are involved in the disease process have been identified, and can be targeted for biological therapy; many of these molecules, which are mainly cytokines, are directly involved in the immune system. Biological therapy has found a niche in the management of cancer,[2][3] autoimmune diseases,[4] and diseases of unknown cause that result in symptoms due to immune related mechanisms.[5][6]

Inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, is a collection of systemic diseases involving inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.[7] IBD includes two (or three) diseases of unknown causation: ulcerative colitis, which affects only the large bowel; Crohn's disease, which can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract; and, indeterminate colitis, which consists of large bowel inflammation that shows elements of both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.[8]

Although the causes of these diseases are unknown, genetic, environmental, immune and other mechanisms have been proposed. Of these, the immune system plays a large role in the development of symptoms.[8] Given this, a variety of biological therapies have been developed for the treatment of these diseases. These have changed the way physicians treat Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.[5][6]

Rationale for biological therapy

Prior to the development of biological therapy as a modality to treat IBD, other medications that modulate the immune system—including 5-aminosalicylates, steroids, azathioprine, and other immunosuppressants—were primarily used in treatment.[7] Patients with Crohn's disease that developed complications, including fistulae (= abnormal connections to the bowel) were treated with surgery.[9] Patients with ulcerative colitis who do not respond to medications are still treated with colectomy (= removal of the colon).

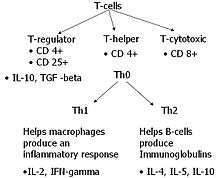

However, basic science research showed that there were many cytokines that were elevated in both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.[10] Crohn's disease cytokines, are of the type 1 (Th1) cytokines which include TNF-α, interleukin-2, and interferon γ.[11] Ulcerative colitis was less conclusively linked to the production of Th2 cytokines.[12]

Infliximab

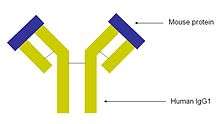

The monoclonal antibody infliximab is a mouse-human chimeric antibody to TNF-α. It first was used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis,[13] and was the first biological agent used in the treatment of IBD. It is also used in the treatment of psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitis.[14][15] Infliximab has shown significant success in treating Crohn's disease.[5]

Other monoclonal antibodies

Other biological therapy agents and monoclonal antibodies have not showed as much efficacy in the treatment of IBD. These include etanercept (which is the soluble receptor for TNF.[16] Adalimumab (which is a humanized recombinant antibody to TNF) showed effectiveness in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease, but less than that of infliximab.[17] It however conveys an advantage in that it is given by subcutaneous injection as opposed to infliximab, which is given by intravenous infusion.

In 2005, two other recombinant medications were reported to have benefit in moderate to severe Crohn's disease. Certolizumab is a Fab fragment of a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody that is attached to polyethylene glycol to increase its half-life in circulation. It was found to have efficacy over placebo medications for 10 weeks in the treatment of moderate to severe Crohn's disease in one large trial.[18] Natalizumab is an anti-integrin monoclonal antibody that shown utility as induction and maintenance treatment for moderate to severe Crohn's disease.[19] However, it has been associated with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a usually fatal viral infection of the brain, that may limit its use.[20]

Side effects and concerns

There have been concerns about the side effects of monoclonal antibodies, and specifically of infliximab, but these are rare. Early side effects include the risk of allergic reactions (including anaphylaxis which may be life-threatening), and reactions to the infusion. These are often treated with medications given before treatment. Infliximab also carries a risk of worsening infection, and can cause reactivation of old infections, like tuberculosis. Over time, there is the risk of serum sickness, which is a delayed hypersensitivity response to the medication. Later complications may include multiple sclerosis and lymphoma. Finally, the medication is quite expensive, with treatment costs ranging from US$3000 to $8000 per infusion.[21][22][23]

Loss of response to infliximab over time is a concern, due to the development of antibodies to infliximab (termed human anti-chimeric antibodies, or HACA). This can be reduced by concurrent treatment with other immunosuppressant medications (including azathioprine and methotrexate), by maintaining a regular infusion schedule, and by giving patients a pre-treatment dose of steroid medication.[24]

Biologic agents may promote developing malignancies due to they act on the immune system.[25]

Research

Gram positive bacteria present in the lumen could be associated with extending the time of relapse for ulcerative colitis.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ Staren E, Essner R, Economou J (1989). "Overview of biological response modifiers.". Semin Surg Oncol. 5 (6): 379–84. doi:10.1002/ssu.2980050603. PMID 2480627.

- ↑ Talpaz M, Kantarjian H, McCredie K, Trujillo J, Keating M, Gutterman J (1987). "Therapy of chronic myelogenous leukemia.". Cancer. 59 (3 Suppl): 664–7. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19870201)59:3+<664::AID-CNCR2820591316>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 10822467.

- ↑ Kalinski P, Mapara M (2006). "9th Annual Meeting of the Regional Cancer Consortium for the Biological Therapy of Cancer. 16–18 February 2006, UPMC Herberman Conference Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.". Expert Opin Biol Ther. 6 (6): 631–3. doi:10.1517/14712598.6.6.631. PMID 16706609.

- ↑ Weinblatt M, Kremer J, Bankhurst A, Bulpitt K, Fleischmann R, Fox R, Jackson C, Lange M, Burge D (1999). "A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate.". N Engl J Med. 340 (4): 253–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901283400401. PMID 9920948.

- 1 2 3 Hanauer S, Feagan B, Lichtenstein G, Mayer L, Schreiber S, Colombel J, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf D, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P (2002). "Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial.". Lancet. 359 (9317): 1541–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. PMID 12047962.

- 1 2 Rutgeerts P, Sandborn W, Feagan B, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer S, Lichtenstein G, de Villiers W, Present D, Sands B, Colombel J (2005). "Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis.". N Engl J Med. 353 (23): 2462–76. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050516. PMID 16339095.

- 1 2 Hanauer, Stephen B.; Hanauer, Stephen B. (March 1996). "Inflammatory bowel disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (13): 841–848. doi:10.1056/NEJM199603283341307. PMID 8596552.

- 1 2 Podolsky, Daniel K. (August 2002). "Inflammatory bowel disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (6): 417–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020831. PMID 12167685.

- ↑ Williams J (1971). "The place of surgery in Crohn's disease". Gut. 12 (9): 739–49. doi:10.1136/gut.12.9.739. PMC 1411802

. PMID 4938523.

. PMID 4938523. - ↑ Pallone F, Monteleone G (1996). "Regulatory cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 10 Suppl 2: 75–9; discussion 80. PMID 8899105.

- ↑ Romagnani S (1999). "Th1/Th2 cells". Inflamm Bowel Dis. 5 (4): 285–94. doi:10.1002/ibd.3780050410. PMID 10579123.

- ↑ Inoue S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Mizuno M, Kuroki F, Hoshika K, Shimizu M (1999). "Characterization of cytokine expression in the rectal mucosa of ulcerative colitis: correlation with disease activity". Am J Gastroenterol. 94 (9): 2441–6. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01372.x. PMID 10484006.

- ↑ Elliott M, Maini R, Feldmann M, Kalden J, Antoni C, Smolen J, Leeb B, Breedveld F, Macfarlane J, Bijl H (1994). "Randomised double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor alpha (cA2) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis". Lancet. 344 (8930): 1105–10. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90628-9. PMID 7934491.

- ↑ Chaudhari U, Romano P, Mulcahy L, Dooley L, Baker D, Gottlieb A (2001). "Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomised trial". Lancet. 357 (9271): 1842–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04954-0. PMID 11410193.

- ↑ Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Golder W, Gromnica-Ihle E, Kellner H, Krause A, Schneider M, Sörensen H, Zeidler H, Thriene W, Sieper J (2002). "Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial". Lancet. 359 (9313): 1187–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08215-6. PMID 11955536.

- ↑ Sandborn W, Hanauer S, Katz S, Safdi M, Wolf D, Baerg R, Tremaine W, Johnson T, Diehl N, Zinsmeister A (2001). "Etanercept for active Crohn's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Gastroenterology. 121 (5): 1088–94. doi:10.1053/gast.2001.28674. PMID 11677200.

- ↑ Hanauer S, Sandborn W, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak R, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P (2006). "Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn's disease: the CLASSIC-I trial". Gastroenterology. 130 (2): 323–33; quiz 591. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. PMID 16472588.

- ↑ Schreiber S, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak R, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Kamm M, Boivin M, Bernstein C, Staun M, Thomsen O, Innes A (2005). "A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol (CDP870) for treatment of Crohn's disease". Gastroenterology. 129 (3): 807–18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.064. PMID 16143120.

- ↑ Sandborn W, Colombel J, Enns R, Feagan B, Hanauer S, Lawrance I, Panaccione R, Sanders M, Schreiber S, Targan S, van Deventer S, Goldblum R, Despain D, Hogge G, Rutgeerts P (2005). "Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease". N Engl J Med. 353 (18): 1912–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043335. PMID 16267322.

- ↑ Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, Dubois B, Vermeire S, Noman M, Verbeeck J, Geboes K, Robberecht W, Rutgeerts P (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease". N Engl J Med. 353 (4): 362–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051586. PMID 15947080.

- ↑ Blonski W, Lichtenstein G (2006). "Safety of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease". Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 9 (3): 221–33. doi:10.1007/s11938-006-0041-4. PMID 16901386.

- ↑ Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S (2006). "Review article: Infliximab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease--seven years on". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 23 (4): 451–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02786.x. PMID 16441465.

- ↑ Siegel C, Hur C, Korzenik J, Gazelle G, Sands B (2006). "Risks and benefits of infliximab for the treatment of Crohn's disease". Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 4 (8): 1017–24; quiz 976. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.020. PMID 16843733.

- ↑ Sandborn W (2003). "Optimizing anti-tumor necrosis factor strategies in inflammatory bowel disease". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 5 (6): 501–5. doi:10.1007/s11894-003-0040-8. PMID 14602060.

- ↑ Axelrad, JE; Lichtiger, S; Yajnik, V (28 May 2016). "Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: The role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment.". World journal of gastroenterology. 22 (20): 4794–801. PMID 27239106.

- ↑ Ghouri, Yezaz A; Richards, David M; Rahimi, Erik F; Krill, Joseph T; Jelinek, Katherine A; DuPont, Andrew W (9 December 2014). "Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in inflammatory bowel disease". Clin Exp Gastroenterol. pp. 473–487. doi:10.2147/CEG.S27530. Retrieved 17 May 2016.