Bharwad

The Bharwad are a Hindu caste found in the state of Gujarat in India.

Etymology

The Bharwad name may derive from the Gujarati word badawad, constructed from bada (sheep) and wada (a compound or enclosure). Gadaria is another word that may have the same origin. In the Saurashtra region of western Gujarat they exist as two endogamous groups, known as the Mota Bhai (Motabhai) and the Nana Bhai (Nanabhai).[1] Bharwads in the Saurashtra region often append Ahir to their names, while in south Gujarat it is common to see Patel appended.[1]

Origin

The Bharwads consider themselves to be descended from the mythological Nandvanshi line that began with Nanda, the foster-father of Krishna. Legend has it that Nanda came from Gokul, in Mathura district, and passed through Saurashtra on his way to Dwarka.[2] According to their traditions, the Bharwads were at some time based around Mathura and migrated to Mewar before later spreading out in Gujarat.[1] Sudipta Mitra considers their move to Gujarat to have been predicated by a desire to keep away from the Muslim invasion of Sind. They arrived in the northern town of Banaskantha in 961 CE and later spread out to Saurashtra and other areas.[2]

There are other theories of origin. These include that they are an offshoot of the Bharude cattle-herders of Madhya Pradesh and that they are descendants of Anavil Bharwad, who helped a Chavda prince regain his kingdom. It is also possible that they are related to the Ahirs of Gujarat, with whom they share a common traditional occupation.[1]

Divisions

Of the various reasons given for the division between Motabhai and Nanabhai, the most popular is that two shepherd brothers were ordered by Krishna to take their flocks to different places. The older of the brothers went on to marry a Bharwad woman while the other married a Koli. Since the latter was a marriage outside the community, the offspring were deemed to be ritually polluted. Thus the Motabhai (literally, "big brother") descend from the first and the Nanabhai ("little brother") from the latter.[3]

The Bharwads have numerous subgroups known as ataks or guls (clans) whose main purpose is to determine eligibility for marriage. A constrained exogamy is practised between clans[lower-alpha 1] but endogamy exists between the two Saurashtrian divisions despite there being no other social constraints on mixing. The Saurashtra Bharwads also hold a higher status than those in the south and thus marriage between the two regional groups operates in one direction only: daughters of southern Bharwads can marry into the family of those from Saurashtra.[1]

Clans of the Mota Bhai Bharwads include the Bambha, Bathela, Golthar, Dabi, Dhangia, Dharangia, Garia, Gamara, Jadav, Kathodi, Ker, Lambriya,Bhundiya,toyta,todiya,junja, fangliya,Mevada, Matia, Mundhva, Pancha, Ratdiya, Sania, Sasda, Tota and Yadav.[1]

Among the Bharwad of south Gujarat, their main clans are the Chandulka, Dahika, Gundarya, Jodika, Kalwamia, Khohadya, Kuhadiya and Rokadka.[1]

Varna and socio-economic status

The varna system of Hinduism is a traditional ritual ranking system based on levels of purported religious purity. Within this four-fold scheme, the Bharwads consider themselves to be Vaishya but they also believe themselves to be equal to Rajput communities that are generally considered to be of the more pure Kshatriya varna. They also believe themselves to be of a higher ritual status than artisan groups such as the Lohars and Suthars.[1]

Despite their own beliefs, the Bharwads are generally treated within regional society as being somewhat below the Brahmin, Vania, Lohana, Patel, Charan and Dharjee communities.[1] Mitra notes that they are generally considered to be among the lowest of the pastoral castes, being engaged primarily in the herding of goats and sheep.[lower-alpha 2] However, although one of the Maldhari nomadic communities, they are also among the most urbanised of the region and, combined with their niche position in the supply of milk, which forms their main source of income, this has enabled them to improve their traditional social position.[4]

Customs

Religion

The Bharwad are Hindu, and like other Hindu pastoral communities pay special reverence to Krishna. Each clan also has its own deity, while their chief goddess is Masai Mata. Their most sacred place is at Morvi and they also make pilgrimages to place such as Dwarka. Some Bharwads in the south have become vegetarian as a consequence of outside influences.[1]

Family arrangements

Members of the community practice monogamy and arranged marriages are traditional, usually accompanied by a ritualised exchange of gifts between the partners.[1] There is anecdotal evidence that pet chandla (marriage of children while they are still in the womb) is practised by some members of the community.[5] In other cases, a sagai (engagement) ceremony takes place when children are aged 2–3, with the marriage age usually being between 18-20 for women and 20-22 for men.[lower-alpha 3] Remarriage in situations where the couple are childless requires the consent of the wife, and divorce is not usually tolerated except in this situation and that of mental infirmity. Remarriage upon widowhood is also accepted but men are expected generally to prefer a younger unmarried sister of their late wife.[1]

Married couples live in a patrilocal arrangement. The Bharwads practice male equigeniture, meaning that property is inherited equally by the male children, and it is the eldest son who becomes head of household on the death of the father. Women have no rights of inheritance over property. Although consulted, they also have no final say in the making of significant decisions.[1]

Clothing

The Bharwads practice "sartorial conservatism", according to Emma Tarlo, and it is not enough to be born a Bharwad if a person wants to be accepted as one: conforming with standards of dress and other customs is a necessity if a person is not to be considered a deserter from the community.[7] The details of clothing — in terms of style, colour and material — have changed over time while retaining a distinct Bharwad character. Despite it being a relatively recent practice, the wearing of pink and red shawls by both women and men is one of the most obvious identifiers of the modern community and they are worn even by those who shun the other aspects of the Bharwadi dress code in favour of Western styles.[8] The desire to identify through clothing and also through tattoos may be a reflection of the community's traditional itinerant lifestyle, whereby a means of recognising their fellows was a significant social factor.[9]

The clothing worn by Bharwad women was traditionally made from coarse wool woven by members of local untouchable communities. In addition, they embroidered their own open-backed bodices. The garments at that time — as late as the early 20th century — comprised the bodice, an unstitched black or red waist-cloth, known as a jimi, and a veil. Motabhai clothing was made from thicker wool than that of the Nanabhai, leading to the two groups referring to themselves as "thick cloth" and "thin cloth". The veil was dyed black and bore red dots if the woman was a Motabhai and yellow if she was Nanabhai. While the styles and colours remain similar, modern Bharwad women use man-made fibres, such as polyester, and cotton. This change may be in part because the modern materials are of finer texture but it is more likely than it came about because of their relative cheapness. Cost is an important factor among the generally penurious community and women could sell the woollen fabric that they had used for clothing for a greater price than they paid for the replacement man-made fabric clothes.[10] Tarlo quotes a Bharwad woman saying that "If you wear a sari then you can no longer be called a Bharwad. That is the way it is among our caste. Better to die than change your clothes."[11]

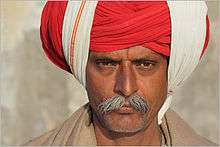

The men commonly wear a silver ear-ring, called a variya, and a pagri (turban). The length of the turban differs between the two divisions,[1] and there are numerous ways of tying them. A white turban, rather than the more usual pink or red, is a symbol of seniority.[12] Wearing Western-style clothing is still not generally accepted but the traditional three woollen blankets, worn around the head, waist and shoulders, have in many cases been replaced by a cotton kediyun together with a dhoti or chorni.[13] As with the women, Carol Henderson notes that

[Bharwads] say that if a man doesn't wear their dress, he ceases to be Bharwad. Being Bharwad means dressing Bharwad. Bharwad men wear a distinctive short gathered smock with long, tight sleeves, massive wound turban, gathered pantaloons, and a shawl.[14]

Occupations

Bharwads are rarely educated beyond primary level and literacy rates are poor. Many of them live in and around the Gir Forest National Park, where they tend to keep away from the forest itself when grazing their livestock due to the danger of attacks by Asiatic lions. Aside from their involvement with livestock, the main source of income is agricultural labouring; few of them own land. Many are in Mumbai(sakinaka Dahisar) Rajkot,Surat(mandvi) Jamnagar, Morbi, Ahmadabad, Vadodara etc..

Community associations

There is a hierarchy of nyat panchayats (community councils) for the resolution of disputes. These are headed by chiefs and comprise several other members. The lowest tier of this are those that operate at the level of a single village or of a group of villages if the Bharwad population is small. Matters that cannot be settled at that level are referred upwards to a regional panchayat and thereafter to a central body based at Rajkot. If matters are still not resolved after referral to Rajkot then the parties will seek intervention form law enforcement agencies, although this is rare.[1]

There also exists a community welfare association called the Gujarat Rajya Gopalak Sakahari Sangh, which was formed in 1950 at Ahmedabad. This has worked to document the history and traditions of the Bhardwads and has also established several hundred co-operative societies. In addition, it has worked to bring an end to some traditional social practices that are now deemed to be inappropriate, such as bride price.[1]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ For example, the Rathadia, Jadav and Yadav clans of the Mota Bhai consider that they are socially superior to the other clans and will only marry between themselves.[1]

- ↑ Some Bharwads are cattle-herders but their number is declining.[2]

- ↑ Marriages of six-year-olds have been recorded but most do not marry so young.[6]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Lal et al. (2003), pp. 194-199

- 1 2 3 Mitra (2005), p. 84

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 147

- ↑ Mitra (2005), pp. 65, 84

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 272

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), pp. 155, 253

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), pp. 258, 262-263

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 271-272

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 273

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), pp. xiii, 147, 267

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 257

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 271

- ↑ Tarlo (1996), p. 151

- ↑ Henderson (2002), p. 113

Bibliography

- Henderson, Carol E. (2002), Culture and Customs of India, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 9780313305139

- Lal, Rajendra Behari; Padmanabham, P. B. S. V.; Krishnan, G.; Mohideen, M. Azeez, eds. (2003), People of India Gujarat Volume XXI Part One, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 9788179911044

- Mitra, Sudipta (2005), Gir Forest and the Saga of the Asiatic Lion, Indus Publishing, ISBN 9788173871832

- Tarlo, Emma (1996), Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 9781850651765