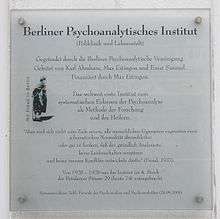

Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute

The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute (later the Göring Institute) was founded in 1920 to further the science of psychoanalysis in Berlin. Its founding members included Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon. The scientists at the institute furthered Sigmund Freud's work but also challenged many of his ideas.

History

The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute grew from the Psychoanalytic Polyclinic (psychoanalytische Poliklinik) founded in February 1920. The Polyclinic allowed access to psychoanalysis by low-income patients. Only some 10% of its income came from patients' fees; the rest was provided personally by Max Eitingon. It introduced the three-column model or 'Eitingon model' for the training of analysts (theoretical courses, personal analysis, first patients under supervision) which was later adopted by most other training centers. In 1925, Eitingon became chair of the new International Training Committee of the International Psychoanalytic Association. The Eitingon model remains standard today.[1]

The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute itself was founded in 1923. Ernst Simmel, Hanns Sachs, Franz Alexander, Sándor Radó, Karen Horney, Siegfried Bernfeld, Otto Fenichel, Theodor Reik, Wilhelm Reich and Melanie Klein were among the many psychoanalysts who worked at the Institute.

As a Jew, Eitingon's position became precarious after the Nazi ascent to power in 1933. Freud's books were burned in Berlin. By then some members had already left Berlin for the USA.[2] Eitingon resigned in August 1933; he later moved to Palestine and founded the Palestine Psychoanalytic Association in 1934 in Jerusalem. The Palestine Association saw itself as the heir of the Berlin Institute; even the furniture from the Berlin Institute ended up in Jerusalem.

On 23 August 1933, Sigmund Freud wrote to Ernest Jones, "Berlin is lost".[3] Edith Jacobson was arrested by the Nazis in 1935; one of her patients was a known Communist. Felix Boehm, who with fellow non-Jew Carl Müller-Braunschweig had taken control of the Institute after Eitingon's departure, refused to intervene on Jacobson's behalf, on the grounds that by associating herself with Communism she had endangered the Institute's survival. In 1936 the Institute was annexed to the "Deutsches Institut für psychologische Forschung und Psychotherapie e.v." (the so called Göring Institute). Its director Matthias Göring was a cousin of Field Marshal Hermann Göring. Göring, Boehm and Müller-Braunschweig collaborated for a number of years; fourteen non-Jewish German psychoanalysts continued to operate within the new Institute. The one remaining copy of Freud's works was kept in a locked cupboard referred to as the "poison cabinet".[4]

John Rittmeister, a physician and psychoanalyst associated with the Institute, as well as resistance fighter against Nazism, was sentenced to death and executed in May 1943.

References

Literature

English

- Geoffrey Cocks, Psychotherapy in the Third Reich—The Göring Institute, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985 (based on his dissertation: Psyche and Swastika: neue deutsche Seelenheilkunde 1933–1945, 1975)

- Geoffrey Cocks, Repressing, Remembering, Working Through: German Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, Psychoanalysis, and the "Missed Resistance" in the Third Reich,The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 64, Supplement: Resistance Against the Third Reich (Dec., 1992), pp. S204-S216.

German

- Zehn Jahre Berliner Psychoanalytisches Institut (Poliklinik und Lehranstalt) / Hrsg. v.d. Dt. Psychoanalyt. Gesellschaft. Mit e. Vorw. v. Sigmund Freud, Wien: Internat. Psychoanalyt. Verl., 1930.

- Bannach, H.-J.: "Die wissenschaftliche Bedeutung des alten Berliner Psychoanalytischen Instituts" In: Psyche 23, 1969, pp. 242–254.

- Regine Lockot, Erinnern und Durcharbeiten: zur Geschichte der Psychoanalyse und Psychotherapie im Nationalsozialismus, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 1985.

French

- Collectif édité pour la France sous la dir.: Alain de Mijolla : "- Ici, la vie continue d'une manière fort surprenante..." : Contribution à l'Histoire de la Psychanalyse en Allemagne., Ed.: Association internationale d'histoire de la psychanalyse, 1987, ISBN 2-85480-153-9