Benjamin Hawkins

| Benjamin Hawkins | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from North Carolina | |

|

In office December 8, 1789 – March 4, 1795 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Timothy Bloodworth |

| Member of the Congress of the Confederation | |

|

In office 1781 – 1783 1787 | |

| Member of the North Carolina House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1778 – 1779 1784 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

August 15, 1754 Granville County, Province of North Carolina, British America |

| Died |

June 6, 1816 (aged 61) Crawford County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Roberta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party |

Pro-Administration (1789–1791) Anti-Administration (1791–1795) |

| Alma mater | College of New Jersey |

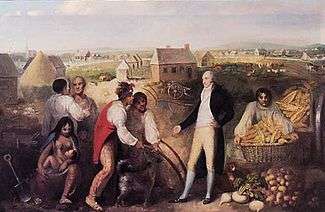

Benjamin Hawkins (August 15, 1754 – June 6, 1816[1]) was an American planter, statesman, and U.S. Indian agent. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite. Appointed by George Washington as General Superintendent for Indian Affairs (1796–1818), he had responsibility for the Native American tribes south of the Ohio River, and was principal Indian agent to the Creek Indians.

Hawkins established the Creek Agency and his plantation in present-day Georgia, where he lived in what became Crawford County. He learned the Muscogee language, was adopted by the tribe and married Lavinia Downs, who some believe was a Creek woman, with whom he had seven children. (See marriage and family below) He wrote extensively about the Creek and other Southeast tribes: the Choctaw, Cherokee and Chickasaw. He eventually built a large complex using African slave labor, including mills, and raised a considerable quantity of livestock in cattle and hogs.

Early life and education

Hawkins was born to Philemon and Delia Martin Hawkins on August 15, 1754, the third of four sons. The family farmed and operated a plantation in what was then Granville County, North Carolina, but is now Warren County. He attended the College of New Jersey (later to become Princeton University), but he left college in his last year to join the Continental Army. Hawkins was commissioned a Colonel and served for several years on George Washington's staff as his main interpreter of French.

Career

Hawkins was released from federal service late in 1777, as Washington learned to rely on la Fayette for dealing with the French. He returned home, where he was elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives in 1778. He served there until 1779, and again in 1784. The Carolina Assembly sent him to the Continental Congress as their delegate from 1781 to 1783, and again in 1787.

In 1789, Hawkins was a delegate to the North Carolina convention that ratified the United States Constitution. He was elected to the first U.S. Senate, where he served from 1789 to 1795. Although the Senate did not have organized political parties at the time, Hawkins' views aligned with different groups. Early in his Senate career, he was counted in the ranks of those senators viewed as pro-Administration, but by the third congress, he generally sided with senators of the Republican or Anti-Administration Party.

U.S. Indian Agent

In 1785, Hawkins had served as a representative for the Congress in negotiations over land with the Creek Indians of the Southeast. He was generally successful, and convinced the tribe to lessen their raids for several years, although he could not conclude a formal treaty. The Creek wanted to deal with the 'head man'. They finally signed the Treaty of New York after Hawkins convinced George Washington to become involved.

In 1786, Hawkins and fellow Indian agents Andrew Pickens and Joseph Martin concluded a treaty with the Choctaw nation at Seneca Old Town, today's Hopewell, South Carolina. They set out the boundaries for the Choctaw lands as well as provisions for relations between the tribe and the U.S. government.[2]

In 1789, conditions among the Creeks seemed to indicate an urgency for his return to the Creek country. Accordingly, he left Tennessee early in September for Fort Wilkinson on the Oconee River in Georgia. The next few months were spent with the Creeks. January 1, 1789, was set as the date for the assembling of the commissioners for running the Creek line in conformity to the treaties at New York and Coleraine. Hawkins had some difficulty in persuading the Creeks to agree to the running of the line, as many of the younger warriors were opposed. On February 16 Hawkins reported to Secretary of War, James McHenry that the line had been run from the Tugalo River over Currahee Mountain to the main south branch of the Oconee River. Though about sixteen families of Georgians were found on the Creek lands in the area known as Wofford's Settlement, McHenry was told "...I am happy in being able to assure you that there was no diversity of opinion among us, and that the line was closed in perfect harmony.[3]" This line became known as the Hawkins Line.[4]

In 1796, Washington appointed Benjamin Hawkins as General Superintendent of Indian Affairs, dealing with all tribes south of the Ohio River. As principal agent to the Creek tribe, Hawkins soon moved to present-day Crawford County in Georgia where he established his home and the Creek Agency. He studied the language and was adopted by the Creek. He wrote extensively about them and the other southeast tribes.

Georgia

Hawkins began to teach European-American agricultural practices to the Creek, and started a farm at his and Lavinia's home on the Flint River. In time, he purchased enslaved Africans and hired other workers to clear several hundred acres for his plantation. They built a sawmill, gristmill and a trading post for the agency. Hawkins expanded his operation to include more than 1,000 head of cattle and a large number of hogs. For years, he met with chiefs on his porch and discussed matters there. His personal hard work and open-handed generosity won him such respect that reports say that he never lost an animal to Indian raiders.

He was responsible for 19 years of peace between the settlers and the tribe, the longest such period during European-American settlement. When in 1806 the government built a fort at the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, to protect expanding settlements just east of modern Macon, Georgia, the government named it Fort Benjamin Hawkins in his honor.

Hawkins saw much of his work to preserve peace destroyed in 1812. A group of Creek rebels, known as Red Sticks, were working to revive traditional ways and halt encroachment by European Americans. The ensuing civil war among the Creeks coincided with the War of 1812.

During the Creek War of 1813-1814, Hawkins organized "friendly" Creek Indians under the command of chief William McIntosh to aid Georgia and Tennessee militias in their forays against the traditional Red Sticks.[5] General Andrew Jackson led the defeat of the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in present-day Alabama. Hawkins was unable to attend negotiations of the Treaty of Fort Jackson in August 1814, which required the Creeks to cede most of their territory and give up their way of life. Hawkins later organized "friendly" Creek warriors to oppose a British force on the Apalachicola River that threatened to rally the scattered Red Sticks and reignite the war on the Georgia frontier. After the British withdrew in 1815, Hawkins was organizing another force when he died of a sudden illness in June 1816.

Hawkins tried more than once to resign his post and return from the Georgia frontier, but his resignation was refused by every president after Washington. He remained Superintendent until his death on June 6, 1816. At the end of his life, he formally married Lavinia Downs in a European-American ceremony, making their children legitimate in United States society. They already belonged to Downs' clan among the Creek, who had a matrilineal kinship system. The children gain status from their mother's clan and people, and their mother's eldest brother is usually more important in their lives than their biological father.

Benjamin Hawkins was buried32°40′0.61″N 84°5′45.73″W / 32.6668361°N 84.0960361°W at the Creek Agency near the Flint River and Roberta, Georgia.

Fort Hawkins was built overlooking the ancient site since designated as the Ocmulgee National Monument. Revealing 17,000 years of human habitation, it is a National Historic Landmark and has been sacred for centuries to the Creek. It has massive earthwork mounds built nearly 1,000 years ago as expressions of the religious and political world of the Mississippian culture, the ancestors to the Creek.

Personal life

He made a common-law marriage for years with Lavinia Downs, who some believe was a Creek Indian woman, whereas other evidence indicates that she was a white woman. They had a total of six daughters: Georgia, Muscogee, Cherokee, Carolina, Virginia, and Jeffersonia, and one son, Madison Hawkins.[1] In 1812, thinking he was on his death bed, Hawkins married Lavinia formally to make their children legitimate in US society.[1] Jeffersonia was born after this marriage.

Hawkins was close to his nephew William Hawkins, whom he made a co-executor of his estate along with his wife; he bequeathed to William a share of his estate, reputed to be quite large. This bequest became a source of contention among his heirs, especially as he had not altered his will to include his youngest daughter Jeffersonia.

Legacy and honors

- Hawkinsville, Georgia is named in his honor.[6]

- Hawkins County in Tennessee bears his name.[7]

- He is the namesake of the Benjamin Hawkins Boy Scout Camp near Byron, Georgia.

The archeological site of the original Fort Benjamin Hawkins is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), and it is within the Fort Hill Historic District of Macon, Georgia, also listed on the NRHP.

- Hawkins was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1813.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 "Benjamin Hawkins", Encyclopedia of Alabama, accessed July 15, 2011

- ↑ Horatio Bardwell Cushman, History of Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez Indians, Greenville, Texas: Headlight Printing House, 1899

- ↑ Pound, Merritt B. (1957). Benjamin Hawkins, Indian agent. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780820334516. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ "Hawkins Line". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ↑ Ethridge, Robbie. "Benjamin Hawkins (1754-1816)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Hawkinsville". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 152.

- ↑ American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

Further reading

- Robbie Franklyn Ethridge, Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Thomas Foster, editor. The Collected Works of Benjamin Hawkins, 1796-1810. 2003, University of Alabama Press, ISBN 0-8173-5040-3.

- C. L. Grant, editor. Benjamin Hawkins: Letters, Journals and Writings. 2 volumes. 1980, Beehive Press, volume 1: ISBN 99921-1-543-2, volume 2: ISBN 99938-28-28-9.

- Florette Henri. The Southern Indians and Benjamin Hawkins, 1796-1816. 1986, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-1968-3.

External links

- United States Congress. "Benjamin Hawkins (id: H000368)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-03-04

- Merritt B. Pound, "Benjamin Hawkins, Indian Agent", Digital Library of Georgia

- "Benjamin Hawkins", New Georgia Encyclopedia

- "Benjamin Hawkins", History and Culture, Ocmulgee National Monument, National Park Service

- "Benjamin Hawkins", Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

- "Camp Benjamin Hawkins", Boy Scouts of America

- Creek Agency Old Agency historical marker

- Benjamin Hawkins historical marker

| United States Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

U.S. Senator (Class 3) from North Carolina 1789–1795 Served alongside: Samuel Johnston, Alexander Martin |

Succeeded by Timothy Bloodworth |