Pierre Belon

| Pierre Belon | |

|---|---|

Pierre Belon | |

| Born |

1517 Souletière near Cérans-Foulletourte |

| Died |

1564 Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | |

Pierre Belon (1517–1564) was a French explorer, naturalist, writer and diplomat. Like many others of the Renaissance period, he studied and wrote on a range of topics including ichthyology, ornithology, botany, comparative anatomy, architecture and Egyptology. He is sometimes known as Pierre Belon du Mans, or, in the Latin in which his works appeared, as Petrus Bellonius Cenomanus. Ivan Pavlov called him the "prophet of comparative anatomy".[1]

Life

Belon was born in 1517 at the hamlet of Souletière near Cérans-Foulletourte.[2] His family was not wealthy and as a boy, he worked as an apprentice at an apothecary at Foulletourte. He later (c. 1535) worked as an apothecary to the bishop of Clermont, Guillaume Duprat. He then travelled through Flanders and England, taking a keen interest in zoology. When he returned to Auvergne, he was supported by René du Bellay, bishop of Le Mans, to study at the University of Wittenberg with the botanist Valerius Cordus (1515—1544). He travelled around Germany with Cordus and on his arrival at Thionville, was arrested on suspicions that he was a Lutheran. He was released by the interventions of a certain Dehamme who was an admirer of his friend from Paris, the poet Pierre Ronsard. Around 1542 he studied medicine at Paris, and obtained a licentiate in medicine although he never took the degree of doctor. With the recommendation of Duprat, he became an apothecary to Cardinal François de Tournon. Under this patronage, he was able to undertake extensive scientific voyages. Starting in 1546, he travelled through Greece, Crete, Asia Minor, Egypt, Arabia and Palestine, and returned in 1549. He hoped to find the remains of Homer's Troy in the Levant. A full account of his Observations on this journey, with illustrations, was published in Paris, 1553. Returning to the household of Cardinal de Tournon at Rome for the conclave, Belon encountered the naturalists Guillaume Rondelet and Hippolyte Salviani. He returned to Paris with his copious notes and began to publish. In 1557 he travelled again, this time in northern Italy, Savoy, the Dauphiné and Auvergne.[1][2]

Belon was highly favored both by Henry II and by Charles IX, who accorded him lodging in the Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne; there he undertook the translations of Dioscurides and Theophrastus. He was assassinated one evening in April 1564, when coming through the Bois on his return from Paris.[1][2][3]

Works

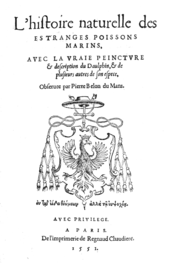

Belon was typical of the renaissance scholar and took an interest in "all kinds of good disciplines" in his lifetime. He was interested in zoology, botany and classical Antiquity. Besides the narrative of his travels he wrote several scientific works of considerable value, particularly the Histoire naturelle des estranges poissons (1551), De aquatilibus (1553). His works were translated by Charles de l'Escluse and he was held in high authority by Ulisse Aldrovandi.

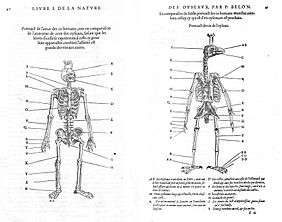

In his L'Histoire de la nature des oyseaux (1555) he included two figures of the skeletons of humans and birds marking the homologous bones. This is widely used as one of the earliest ideas on comparative anatomy.

Books

All of these were first published in Paris..

- 1551: Histoire de la nature des estranges poissons marins, at that time the concept of fishes included all aquatic animals including mammals and the book included the first French illustration of a hippopotamus.[4]

- 1553: De aquatilibus — A French translation of this treatise on fishes, a foundation of modern ichthyology was published in three editions at Paris, 1555, and the volume was reprinted in Frankfurt and Zurich.

- 1553: De arboribus Coniferis, Resiniferis aliisque semper virentibus..., a basic text on conifers, pines and evergreens.

- 1553 De admirabili operi antiquorum et rerum suspiciendarum praestantia..., treating the funerary customs of Antiquity, in three volumes, of which separate titles head the second, on mummification (De medicato funere seu cadavere condito et lugubri defunctorum ejulatione) and third (De medicamentis nonnullis, servandi cadaveris vim obtinentibus).

- 1553: Les observations de plusieurs singularitez et choses memorables trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie et autres pays étrangèrs.

- 1555: revised edition of the Observations; it was translated into Latin for an international readership de Charles de l'Ecluse, 1589.

- 1555: L'Histoire de la nature des oyseaux.

Memorials

A genus in the plant family Gesneriaceae was named as Bellonia in his honour by Charles Plumier. The saltwater fish genus Belone was also named after him by the preeminent ichthyologist Georges Cuvier, along with the family and order it belongs to, Belonidae and Beloniformes respectively. A statue of Belon was erected at Le Mans in 1887.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Wong, M. (1970). "Belon, Pierre". In C.C. Gillispie. Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's sons. pp. 595–596.

- 1 2 3 Morren, Édouard; Crié, Louis (1885). A la memoire de Pierre Belon, du Mans, 1517-1564 (in French). Liege : A la direction génŕale, Boverie.

- ↑ Delaunay, P. (1926). Pierre Belon naturaliste. Le Mans: Imprimerie Monnoyer.

- ↑ Gudger, E.W. (1934). "The Five Great Naturalists of the Sixteenth Century: Belon, Rondelet, Salviani, Gesner and Aldrovandi: A Chapter in the History of Ichthyology". Isis. 22 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1086/346870.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pierre Belon. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Belon, Pierre. |

- Works by or about Pierre Belon at Internet Archive

- L'Histoire de la nature des oyseaux (1555)

- L'histoire naturelle des estranges poissons marins... (1551)

- Sketch of Pierre Belon

- Travels in the Levant: The Observations of Pierre Belon of Le Mans on Many Singularities and Memorable Things Found in Greece, Turkey, Judaea, Egypt, Arabia and Other Foreign Countries (1553). Translated into English by James Hogarth, with an Introduction by Alexandra Merle. Hardinge Simpole Publishers, 2012.