Architecture of Albania

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Albania |

|---|

|

|

Traditions |

|

Mythology and folklore |

|

Festivals |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Monuments |

|

|

The Architecture of Albania is influenced by Illyrian, Greek, Roman, Ottoman, and Italian architecture, while preserving distinct Albanian features such as the Albanian house. From antiquity to the modern period, cities in Albania have evolved from within the castle to include dwellings, religious, and commercial structures, with constant redesigning of town squares and evolution of building techniques.

From antiquity to 5th century AD

The beginnings of architecture in Albania date to the middle Neolithic age with the discovery of prehistoric dwellings in Dunavec and Maliq. They were built on a wooden platform that rested on stakes stuck vertically into the soil. Prehistoric dwellings in Albania consist of three types: houses enclosed either completely on the ground or half underground, both found in Cakran near Fier, and houses constructed above ground.

From the 5th century BC, the Roman colonies of Apollonia and Dyrrachium flourished, while a number of Illyrian cities emerged such as Byllis, Amantia, Dimali, Albanopolis, and Lissus. They were built on top of the highest hills surrounded by heavily fortified walls. Social structures were also constructed such as the Durrës Colosseum, the temples of Apollonia, Orik, Buthrotum, and various promenades (Stoa), theaters, and stadiums.

Between the 1st and 5th centuries AD, the walls of Dyrrah were reinforced with three protective layers, a hypodrome was constructed, while run off and sanitation systems were perfected. Meanwhile, additional structures were added to the centre of Apollonia such as an odeon, library, and Agonothetes. The period also marks the construction of thermal baths that were of social importance as places of gathering.

-

Monument of Agonothetes in Apollonia

-

Basilica of Butrint

-

Roman Theater Butrint

-

Detail of the late antique cathedral in Byllis

-

Rozafa Castle in Shkodër

Early Christian architecture

One of the early Christian structures is the Basilica. The largest of its kind in Albania is that of Butrint, located in the south-eastern part of the ancient city. In the 5th and 6th centuries, the central plan-based Baptiseri of Butrint emerges, being the biggest of its kind in the Mediterranean world.

7th to 15th centuries

During the Middle Ages, a variety of architecture styles developed in the form of dwelling, defense, worship, and engineering structures. However, some inherited historic structures were damaged by invading Ottoman forces.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the consolidation of the Albanian feudal principalities gave rise to Varosha, or neighborhoods outside city walls. Examples of such developments are the Arberesh principalities centred in Petrele, Kruje and Gjirokastra originating from the feudal castle.

In the 15th century, close attention was given to protective structures such as the castle fortifications of Lezha, Petrela, Devoll, Butrint, and Shkodra. More reconstructions took place in strategic points such as the Castle of Elbasan, Preza, Tepelena, and Vlora, the latter being the most important on the coast.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the great Pashaliks of the period such as the Bushati Family, Ahmet Kurt Pasha, and Ali Pashe Tepelena reconstructed several fortifications such as the Castle of Shkodra, Berat, and Tepelena respectively. It is important to note that Ali Pashe Tepelena embarked on a major castle building campaign throughout Epirus.

-

Skanderbeg Museum in Krujë

-

Fortifications built during Ali Pasha's reign in Butrint

Religious objects

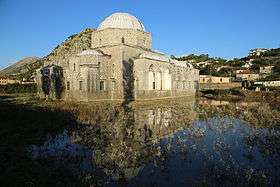

During the medieval period, mosques in Albania fell into two categories: those covered with a dome, and those with a roof covered hall. The latter were immediately adopted following the Ottoman invasion, by transforming the existing churches of Shkodra, Kruje, Berat, Elbasan and Kanina. For instance, the Lead Mosque built by Mustafa Pasha Bushati in Shkodra resembles a typical Istanbul mosque.

On the other hand, Christian religious structures inherited many features from their palaeochristian predecessors. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, a series of small structures for Christian with simple layouts were built like the Voskopoja basilica, Ardenica Monastery, and Church of St. Nicholas in Voskopoja. The latter is one of the most valuable architectonic monuments in Albania. Its interior walls are covered with paintings by the renowned painter David Selenica, and by brothers Constantine and Athanasios Zografi.

-

The Lead Mosque in Shkodër

Medieval town development between the 15th and 19th centuries

During the 18th century, the city silhouette in Albania began to include places of worship and the Clock Tower. These, together with other social structures such as thermal baths, fountains, and medrese further enriched the city centre and its neighborhoods.

In the 19th century, the bazaar emerges as a production and exchange centre, while the city expands beyond the castle, which completely loses its function and inhabitants. During this period, Shkodra and Korca become important commerce and skilled crafts centres.

Medieval cities in Albania are classified according to two criteria:

- Cities associated with fortifications, such as Beret and Gjirokastra

- Cities that lie in flat or steep terrains such as Tirana, Kavaja, and Elbasan.

Albanian dwellings

Albanian dwellings or fortified tower houses (also known as Kulla), flourish between the 18th and 19th centuries as a result of resistance to the Ottoman conquest, Albanian Renaissance movement, and the emergence of capitalism. In most cases, they take the form of an extended family house. However, a house for two brothers can also be found.

Southern Albanian urban or civic Kulla houses are found in Berat, Gjirokastër,[1] Himara, and Këlcyrë.[2] Tower-houses in Gjirokastër were built in the 13th century predating Ottoman conquest.[3] According to their spatial and planning composition, Albanian houses are classified under four groups:[4]

- Houses with vater zjarri, or fireplace/hearth. These houses are found in the Tirana area and characterized by the 'house of fire' (shtepia e zjarrit), which takes up the height of two floors, with surrounding areas interacting around it.

- Houses with hajat, or porch. A distinguishing feature of this style is the relationship of the house with the backyard and natural environment. Oftentimes, these houses are built on flat grounds, with the ground floor used by inhabitants for agricultural purposes. The Shijaku House in Tirana is surrounded by adobe walls with a large gate entrance, and almost always covered with a simple roof.

- Houses with çardak, a type of balcony found on the top floor reserved for guests or relaxation. They are mostly found in Berat, and less so in Kruje and Lezha. The cardak is a dominant element of the building’s outer composition being on the main facade of the house, originally designed to be open. The cardak is extensively used by dwellers in the warm season by exploiting the natural sunlight. It also serves as liaison with other areas of the house. These houses are divided into several sub types: houses with cardak on the front area, on one side, or at the center. An example of such structures is Hajdar Sejdini House in Elbasan.

- Urban or civic kulla. They are found in Gjirokaster (see Zekate House), Berat, Kruje, and Shkoder used for defensive and warehouse purposes. The interior showed the extent of family's wealth, while the ground floor served as a safe place for cattle in the winter, and to keep water reserves for the dry summer months.

Northern Albanian Kulla

Northern Albanian Kulla is a heavily fortified residential building built in northern Albania and Dukagjin region of Kosovo. The Albanian word 'Kulla' means 'Tower' in English. Northern Albanian Kulla contain small windows and shooting holes because their main purpose was to offer security from attack. They were initially built from wood and stone, and eventually only from stone.

The first Kullas that were built are from the 17th century, a time when there was continuous fighting in the Dukagjini region, although most of the ones that still remain are from the 18th or 19th century. They are almost always built within a complex of buildings with various functions but Kullas in villages exist mostly as standalone structures. They are also positioned within the complex of buildings so that the inhabitants can look out over the surrounding area. Kullas in towns are usually built as standalone structures, while in villages they are more commonly found as a part of a larger ensemble of kullas and stone houses, usually grouped together for the family clan they belonged to.

Certain kullë were used as places of isolation and safe havens, or "locked towers" (Albanian: kulla ngujimi), intended for the use of persons targeted by blood feuds (gjakmarrja). An example can be found in Theth, northern Albania.[5] Most Kullas are three-storey buildings. A characteristic unit of its architectural structure in "Oda e burrave" (Chamber of Men or Gathering Room of Men) which was usually placed in the second floor of the Kulla, called Divanhane, while the ground floor served as a barn for cattle and the first floor was where the family quarters were located. The material from which the Divanhane is constructed, either wood or stone, is sometimes used to classify Kullas.[6][7]

Albanian cities in the first half of the 20th century

The first half of the 20th century begins with the Austro-Hungarian occupation, continues with Fan Noli’s government, King Zog’s kingdom, and ends with the Italian invasion. During this time, Albanian medieval towns underwent urban transformations by Austro-Hungarian architects, giving them the appearance of European cities.

The centre of Tirana was the project of Florestano Di Fausto and Armando Brasini, well known architects of the Benito Mussolini period in Italy. Brasini laid the basis for the modern-day arrangement of the ministerial buildings in the city centre. The plan underwent revisions by the Albanian architect Eshref Frashëri, the Italian architect Castellani, and the Austrian architects Weiss and Kohler. The rectangular parallel road system of Tirana e Re district took shape, while the northern portion of the main Boulevard was opened. These urban plans formed the basis of future developments in Albania after WW2.

Communism and post-communist period

From 1944 to 1991, cities experienced an ordered development with a decline in architectural quality. Massive socialist-styled apartment complexes, wide roads, and factories were constructed, while town squares were redesigned and a number of historic buildings demolished.

The period after the fall of communism is often described negatively in terms of urban development. Kiosks and apartment buildings started to occupy former public areas without planning, while informal districts formed around cities from internal migrants leaving remote rural areas for the western lowland. Decreasing urban space and increased traffic congestion have become major problems as a result of lack of planning. As part of the 2014 Administrative Division Reform, all town centres in Albania are being physically redesigned and façades painted to reflect a more Mediterranean look.[8][9]

Although much has been achieved, critics argue that there is no clear vision on Tirana's future. Some of the pressing issues facing Tirana are loss of public space due to illegal and chaotic construction, unpaved roads in suburban areas, degradation of Tirana's Artificial Lake, rehabilitation of Skanderbeg Square, an ever present smog, the construction of a central bus station and lack of public parking space. Future plans include the construction of the Multimodal Station of Tirana and the tram line, rehabilitation of the Tiranë River area, construction of a new boulevard along the former Tirana Railway Station and the finishing of the Big Ring Road.

References

- ↑ Stubbs-Makaš 2011, p. 392

- ↑ Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. p. 334

- ↑ Internationale Tourismusattraktionen in Mittel- und Südosteuropa. Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut, 1999, p. 2.

- ↑ http://acp.al/post.php?id=56

- ↑ Marika McAdam; Jayne d' Arcy; Chris Deliso; Peter Dragicevic (2 May 2009). Western Balkans. Lonely Planet. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-74104-729-5. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Limani, Jeta. "Kulla of Mazrekaj family in Dranoc" (PDF).

- ↑ Doli, Flamur (2009). Arkitektura Vernakulare në Kosovë. Prishtinë: Association for the Preservation of Architectonic Heritage - SHRTA. pp. 93–97. ISBN 9789951878609.

- ↑ "Ndarja e re, mbeten 28 bashki, shkrihen komunat | Shekulli Online". Shekulli.com.al. 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ↑ "Reforma Territoriale - KRYESORE". Reformaterritoriale.al. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

Further reading

- Ledita Mezini a & Dorina Pojani (2014). "Defence, identity, and urban form: the extreme case of Gjirokastra" (PDF). Planning Perspectives.

- Shumka, L (November 2013). "Considering Importance of Light in the Post-Byzantine Church in Central Albania". International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology. 2 (11).

- Eleni Gavra, Stella Kasidou & Yannis Konstantinou. "Management of the Architectural Heritageof the Historic Centre of Korça." (PDF). Institutional Framework and Policies, Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Vokshi, Armand, & Nepravishta, Florian. "FLORESTANO DI FAUSTO - THE GENESIS OF NEW ARCHITECTURAL FORMS IN ALBANIA".

- Ndreçka, Olisa, & Nepravishta, Florian (September 2014). "The Impact of Socialist Realism in the Albanian Architecture in 1945-1990". Architecture and Urban Planning.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of Albania. |

- Architecture of Kosovo

- Bunkers in Albania

- Albanian resistance during World War II - Lapidar monuments commemorating Albanian WW2 Resistance

.jpg)