Anti-torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of passive defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofitting) partially water-filled compartmentalized sponsons on either side of a ship's hull, intended to detonate torpedoes, absorb their explosions, and contain flooding to damaged areas within the bulges.

Application

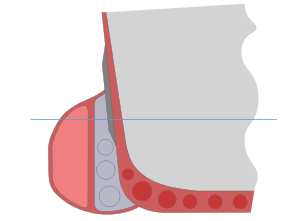

Essentially, the bulge is a compartmentalized, below the waterline sponson isolated from the ship's internal volume. It is part air-filled, and part free-flooding. In theory, a torpedo strike will rupture and flood the bulge's outer air-filled component while the inner water-filled part dissipates the shock and absorbs explosive fragments, leaving the ship's main hull structurally intact. Transverse bulkheads within the bulge limit flooding to the damaged area of the structure.

The bulge was developed by the British Director of Naval Construction, Eustace Tennyson-D'Eyncourt, who had four old Edgar-class protected cruisers so fitted in 1914. These ships were used for shore bombardment duties, and so were exposed to inshore submarine and torpedo boat attack. Grafton was torpedoed in 1917, and apart from a few minor splinter holes, the damage was confined to the bulge and the ship safely made port. Edgar was hit in 1918; this time damage to the elderly hull was confined to dented plating.

The Royal Navy had all new construction fitted with bulges from 1914, beginning with the Revenge-class battleships and Renown-class battlecruisers. It also had its large monitors fitted with enormous bulges. This was fortunate for Terror, which survived three torpedoes striking the hull forward, and for her sister Erebus, which survived a direct hit from a remotely-controlled explosive motor boat that ripped off 50 feet (15.25 m) of her bulge.

Older ships also had bulges incorporated during refit, such as the U.S. Navy's Pennsylvania class, laid down during World War I and retrofitted 1929-31. Japan's Yamashiro had them added in 1930.

Later designs of bulges incorporated various combinations of air and water filled compartments and packing of wood and sealed tubes. As bulges increased a ship's beam, they caused a reduction in speed, which is a function of the length-to-beam ratio. Therefore, various combinations of narrow and internal bulges appeared throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. The bulge had disappeared from construction in the 1930s, being replaced by internal arrangements of compartments with a similar function. An additional reason for the bulges' obsolescence was advances in torpedo design. In particular, the proximity fuze allowed torpedoes to run beneath a target's hull and explode there, beyond the bulges, rather than needing to strike the side of the ship directly.

See also

- Torpedo belt, a later development of torpedo defense system. Essentially a torpedo bulge built on the inside of the hull so as to not protrude and cause unnecessary drag.

- Torpedo net, earlier torpedo defense system - far more effective, but could only be used whilst stationary.

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ The inner bulge is free-flooding and filled with water. The outer layer is filled with air. Lateral baffles prevent the entire bulge flooding in the event of it being pierced. Notice that the main armor belt (dark grey) only extends to just below the waterline.

- Bibliography

- Brown, Derek K. (2003). The Grand Fleet; Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-84067-531-4.

External links

- St. Petersburg Daily Times - Mar 2, 1919 - Blister stops explosion of sub torpedoes

- A detailed discussion of the evolution of Torpedo defense systems ~WWII