Altitudinal zonation

Altitudinal zonation in mountainous regions describes the natural layering of ecosystems that occurs at distinct altitudes due to varying environmental conditions. Temperature, humidity, soil composition, and solar radiation are important factors in determining altitudinal zones, which consequently support different vegetation and animal species.[1][2] Altitudinal zonation was first hypothesized by geographer Alexander von Humboldt who noticed that temperature drops with increasing elevation.[3] Zonation also occurs in intertidal and marine environments, as well as on shorelines and in wetlands. Scientist C. Hart Merriam observed that changes in vegetation and animals in altitudinal zones map onto changes expected with increased latitude in his concept of life zones. Today, altitudinal zonation represents a core concept in mountain research.

Factors

A variety of environmental factors determines the boundaries of altitudinal zones found on mountains, ranging from direct effects of temperature and precipitation to indirect characteristics of the mountain itself, as well as biological interactions of the species. The cause of zonation is complex, due to many possible interactions and overlapping species ranges. Careful measurements and statistical tests are required prove the existence of discrete communities along an elevation gradient, as opposed to uncorrelated species ranges.[5]

Temperature

Decreasing air temperature usually coincides with increasing elevation, which directly influences the length the growing season at different altitudes of the mountain.[1][6] For mountains located in deserts, extreme high temperatures also limit the ability of large deciduous or coniferous trees to grow near the base of mountains.[7] In addition, plants can be especially sensitive to soil temperatures and can have specific elevation ranges that support healthy growth.[8]

Humidity

The humidity of certain zones, including precipitation levels, atmospheric humidity, and potential for evapotranspiration, varies with altitude and is a significant factor in determining altitudinal zonation.[2] The most important variable is precipitation at various altitudes.[9] As warm, moist air rises up the windward side of a mountain, the air temperature cools and loses its capacity to hold moisture. Thus, the greatest amount of rainfall is expected at mid-altitudes and can support deciduous forest development. Above a certain elevation the rising air becomes too dry and cold, and thus discourages tree growth.[8] Although rainfall may not be a significant factors for some mountains, atmospheric humidity or aridity can be more important climatic stresses that affect altitudinal zones.[10] Both overall levels of precipitation and humidity influence soil moisture as well. One of the most important factors that controls the lower boundary of the encinal or forest level is the ratio of evaporation to soil moisture.[11]

Soil composition

The nutrient content of soils at different altitudes further complicates the demarcation of altitudinal zones. Soils with higher nutrient content, due to higher decomposition rates or greater weathering of rocks, better support larger trees and vegetation. The altitude of better soils varies with the particular mountain being studied. For example, for mountains found in the tropical rain forest regions, lower elevations exhibit fewer terrestrial species because of the thick layer of dead fallen leaves covering the forest floor.[2] At this latitude more acidic, humose soils exist at higher elevations in the montane or subapline levels.[2] In a different example, weathering is hampered by low temperatures at higher elevations in the Rocky Mountain of the western United States, resulting in thin coarse soils.[12]

Biological forces

In addition to physical forces, biological forces may also produce zonation. For example, a strong competitor can force weaker competitors to higher or lower positions on the elevation gradient.[13] The importance of competition is difficult to assess without experiments, which are expensive and often take many years to complete. However, there is an accumulating body of evidence that competitively dominant plants may seize the preferred locations (that is warmer sites or deeper soils).[14][15] Two other biological factors can influence zonation: grazing and mutualism. The relative importance of these factors is also difficult to assess, but the abundance of grazing animals, and the abundance of mycorrhizal associations, suggests that these elements may influence plant distributions in significant ways.[16]

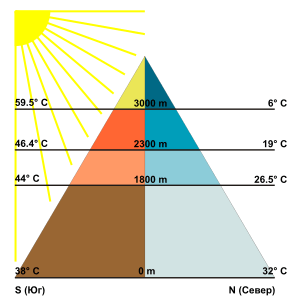

Solar radiation

Light is another significant factor in the growth of trees and other photosynthetic vegetation. The earth’s atmosphere is filled with water vapor, particulate matter, and gases that filter the radiation coming from the sun before reaching the earth’s surface.[17] Hence, the summits of mountains and higher elevations receive much more intense radiation than the basal plains. Along with the expected arid conditions at higher elevations, shrubs and grasses tend to thrive because of their small leaves and extensive root systems.[18] However, high elevations also tend to have more frequent cloud cover, which compensates for some of the high intensity radiation.

Massenerhebung effect

The physical characteristics and relative location of the mountain itself must also be considered in predicting altitudinal zonation patterns.[2] The Massenerhebung effect describes variation in the tree line based on mountain size and location. This effect predicts that zonation of rain forests on lower mountains may mirror the zonation expected on high mountains, but the belts occur at lower altitudes.[2] A similar effect is exhibited in the Santa Catalina Mountains of Arizona, where the basal elevation and the total elevation influence the altitude of vertical zones of vegetation.[11]

Other factors

In addition to the factors described above, there are a host of other properties that can confound predictions of altitudinal zonations. These include: frequency of disturbance (such as fire or monsoons), wind velocity, type of rock, topography, nearness to streams or rivers, history of tectonic activity, and latitude.[1][2]

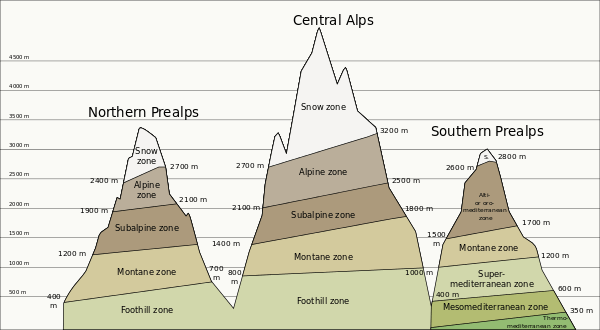

Elevation levels

Elevation models of zonation are complicated by factors discussed above and thus the relative altitudes each zone begins and ends is not tied to a specific altitude.[19] However it is possible to split the altitudinal gradient into five main zones used by ecologists under varying names. In some cases these level follow each other with the decrease in altitude, which is called vegetation inversion.

- Nival level (glaciers):[20] Covered in snow throughout most of the year. Vegetation is extremely limited to only a few species that thrive on silica soils.[6][19]

- Alpine level:[6][19] The zone that stretches between the tree line and snowline. This zone is further broken down into Sub-Nival and Treeless Alpine (in the tropics-Tierra fria; low-alpine)

- Sub-nival:[19] The highest zone that vegetation typically exists. This area is shaped by the frequent frosts that restrict extensive plant colonization. Vegetation is patchy and is restricted to only the most favorable locations that are protected from the heavy winds that often characterize this area. Much of this region is patchy grassland, sedges and rush heaths typical of arctic zones . Snow is found in this region for part of the year.

- Treeless alpine (low-alpine): Characterized by a closed carpet of vegetation that includes alpine meadows, shrubs and sporadic dwarfed trees. Because of the complete cover of vegetation, frost has less of an effect on this region, but due to the consistent freezing temperatures tree growth is severely limited.

- Montane level:[6][21] Extends from the mid-altitude forests to the tree line. The exact level of the tree line varies with local climate, but typically the tree line is found where mean monthly soil temperatures never exceed 10.0 degrees C and the mean annual soil temperatures are around 6.7 degrees C. In the tropics, this region is typified by montane rain forest (above 3,000 ft) while at higher latitudes coniferous forests often dominate.

- Lowland layer:[3][22] This lowest section of mountains varies distinctly across climates and is referred to by a wide range of names depending on the surrounding landscape. Colline zones are found in tropical regions and Encinal zones and desert grasslands are found in desert regions.

- Colline (tropics):[2] Characterized by deciduous forests when in oceanic or moderately continental areas, and characterized by grassland in more continental regions. Extends from sea level to about 3,000 feet (roughly 900 m). Vegetation is abundant and dense. This zone is the typical base layer of tropical regions.

- Encinal (deserts):[11] Characterized by open evergreen oak forests and most common in desert regions. Evaporation and soil moisture control limitation of which encinal environments can thrive. Desert grasslands lie below encinal zones. Very commonly found in the Southwestern United States.

- Desert grassland:[11] Characterized by varying densities of low lying vegetation, grasslands zones cannot support trees due to extreme aridity. Some desert regions may support trees at base of mountains however, and thus distinct grasslands zones will not form in these areas.

For detailed breakdowns of the characteristics of altitudinal zones found on different mountains, see List of life zones by region.

Animal zonation

Animals also exhibit zonation patterns in concert with the vegetational zones described above.[6] Invertebrates are more clearly defined into zones because they are typically less mobile than vertebrate species. Vertebrate animals often span across altitudinal zones according to the seasons and food availability. Typically animal species diversity and abundance decrease as a function of altitude above the montane zone because of the harsher environmental conditions experienced at higher altitudes. Fewer studies have explored animal zonation with altitude because this correlation is less defined than the vegetation zones due to the increased mobility of animal species.[6]

Land-use planning and human utilization

The variability of both natural and human environments has made it difficult to construct universal models to explain human cultivation in altitudinal environments. With more established roads however, the bridge between different cultures has started to shrink.[23] Mountainous environments have become more accessible and diffusion of ideas, technology, and goods occur with more regularity. Nonetheless, altitudinal zonation caters to agricultural specialization and growing populations cause environmental degradation.

Agriculture

Human populations have developed agricultural production strategies to exploit varying characteristics of altitudinal zones. Altitude, climate, and soil fertility set upper limits on types of crops that can reside in each zone. Populations residing in the Andes Mountain region of South America have taken advantage of varying altitudinal environments to raise a wide variety of different crops.[10] Two different types of adaptive strategies have been adopted within mountainous communities.[24]

- Generalized Strategy – exploits a series of microniches or ecozones at several altitudinal levels

- Specialized Strategy – focuses on a single zone and specializes in the agricultural activities suitable to that altitude, developing elaborate trade relationships with external populations

With improved accessibility to new farming techniques, populations are adopting more specialized strategies and moving away from generalized strategies. Many farming communities now choose to trade with communities at different altitudes instead of cultivating every resource on their own because it is cheaper and easier to specialize within their altitudinal zone.[23]

Environmental degradation

Population growth is leading to environmental degradation in altitudinal environments through deforestation and overgrazing. The increase in accessibility of mountainous regions allows more people to travel between areas and encourage groups to expand commercial land use. Furthermore, the new linkage between mountainous and lowland populations from improved road access has contributed to worsening environmental degradation.[23]

Debate on continuum versus zonation

Not all mountainous environments exhibit sudden changes in altitudinal zones. Though less common, some tropical environments show a slow continuous change in vegetation over the altitudinal gradient and thus do not form distinct vegetation zones.[25]

See also

Examples

- Life zones of central Europe

- Life zones of the Mediterranean region

- Life zones of the North Cascades in the Pacific Northwest of America

- Life zones of the Sierra Nevada in California

- Life zones of the Great Basin of North America

- Life zones of Peru

References

- 1 2 3 Daubenmire 1943

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Frahm & Gradstein 1991

- 1 2 Salter et al. 2005

- ↑ Fukarek, F; Hempel, I; Hûbel, G; Sukkov, R; Schuster, M (1982). Flora of the Earth (in Russian). 2. Moscow: Mir. p. 261.

- ↑ Shipley, B.; Keddy, P.A. (1987). "The individualistic and community-unit concepts as falsifiable hypotheses". Vegetation. 69: 47–55. doi:10.1007/BF00038686.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nagy & Grabherr 2009

- ↑ Daubenmire 1943, pp. 345–349

- 1 2 Nagy & Grabherr 2009, pp. 30–35

- ↑ Daubenmire 1943, pp. 349–352

- 1 2 Stadel 1990

- 1 2 3 4 Shreve 1922

- ↑ Daubenmire 1943, p. 355

- ↑ Keddy, P.A. (2001). Competition (2nd ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer. p. 552.

- ↑ Goldberg, D.E. (1982). "The distribution of evergreen and deciduous trees relative to soil type: an example from the Sierra Madre, Mexico, and a general model". Ecology. 63 (4): 942–951. doi:10.2307/1937234. JSTOR 1937234.

- ↑ Wilson, S.D. (1993). "Competition and resource availability in heath and grassland in the Snowy Mountains of Australia". Journal of Ecology. 81 (3): 445–451. doi:10.2307/2261523. JSTOR 2261523.

- ↑ Keddy, P.A. (2007). Plants and Vegetation: Origins, Processes, Consequences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 666.

- ↑ Daubenmire 1943, p. 345

- ↑ Nagy & Grabherr 2009, p. 31

- 1 2 3 4 Troll 1973

- ↑ Pauli, Gottfried & Grabherr 1999

- ↑ Tang & Ohsawa 1997

- ↑ Pulgar Vidal 1941, pp. 145–161

- 1 2 3 Allan 1986

- ↑ Rhoades & Thompson 1975

- ↑ Hemp 2006

Sources

- Allan, Nigel (August 1986). "Accessibility and Altitudinal Zonation Models of Mountains". Mountain Research and Development. International Mountain Society. 6 (3): 185–194. doi:10.2307/3673384. JSTOR 3673384.

- Daubenmire, R.F. (June 1943). "Vegetational Zonation in the Rocky Mountains". Botanical Review. 9 (6): 325–393. doi:10.1007/BF02872481.

- Frahm, Jan-Peter; Gradstein, S. Rob. (Nov 1991). "An Altitudinal Zonation of Tropical Rain Forests Using Bryophytes". Journal of Biogeography. 18 (6): 669–678. doi:10.2307/2845548. JSTOR 2845548.

- Hemp, Andreas (May 2006). "Continuum or Zonation? Altitudinal Gradients in the Forest Vegetation of Mt. Kilimanjaro". Plant Ecology. 184 (1): 27. doi:10.1007/s11258-005-9049-4.

- Hemp, Andreas (2006a). "The banana forests of Kilimanjaro. Biodiversity and conservation of the agroforestry system of the Chagga Home Gardens". Biodiversity and Conservation. 15 (4): 1193–1217. doi:10.1007/s10531-004-8230-8.

- Nagy, Laszlo; Grabherr, Georg (2009). The Biology of Alpine Habitats: Biology of Habitats. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 28–50. ISBN 978-0-19-856703-5.

- Pauli, H.; Gottfried, M.; Grabherr, G. (1999). "Vascular Plant Distribution Patterns at the Low-Temperature Limits of Plant Life - the Alpine-Nival Ecotone of Mount Schrankogel (Tyrol, Austria)". Phytocoenologia. 29 (3): 297–325. doi:10.1127/phyto/29/1999/297.

- Pulgar Vidal, Javier (1979). Geografía del Perú; Las Ocho Regiones Naturales del Perú. Lima: Edit. Universo S.A., note: 1st Edition (his dissertation of 1940); Las ocho regiones naturales del Perú, Boletín del Museo de Historia Natural „Javier Prado“, n° especial, Lima, 1941, 17, pp. 145–161.

- Rhoades, R.E.; Thompson, S.I. (1975). "Adaptive strategies in alpine environments: Beyond ecological particularism". American Ethnologist. 2 (3): 535–551. doi:10.1525/ae.1975.2.3.02a00110.

- Salter, Christopher; Hobbs, Joseph; Wheeler, Jesse; Kostbade, J. Trenton (2005). Essentials of World Regional Geography 2nd Edition. New York: Harcourt Brace. pp. 464–465.

- Shreve, Forrest (Oct 1922). "Conditions Indirectly Affecting Vertical Distribution on Desert Mountains" (PDF). Ecology. 3 (4): 269–274. doi:10.2307/1929428. JSTOR 1929428. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- Stadel, Christoph (October 1990). "Altitudinal Belts in the Tropical Andes: Their Ecology and Human Utilization". In Tom L. Martinson. Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers, Benchmark 1990. Auburn, Alabama. pp. 45–60. JSTOR 25765738.

- Tang, C. Q.; Ohsawa, M. (1997). "Zonal Transition of Evergreen, Deciduous, and Coniferous Forests Along the Altitudinal Gradient on a Humid Subtropical Mountain, Mt. Emei, Sichuan, China". Plant Ecology. 133 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1023/A:1009729027521.

- Troll, Carl (1973). "High Mountain Belts between the Polar Caps and the Equator: Their Definition and Lower Limit". Arctic and Alpine Research. 5. Proceedings of the Symposium of the International Geographical Union Commission on High Altitude Geoecology A19-27. JSTOR 1550149.