All Writs Act

The All Writs Act is a United States federal statute, codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1651, which authorizes the United States federal courts to "issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law."

The act in its original form was part of the Judiciary Act of 1789. The current form of the act was first passed in 1911[1] and the act has been amended several times since then,[2] but it has not changed significantly in substance since 1789.[3]

Act

The text of the Act is:[2]

(a) The Supreme Court and all courts established by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.(b) An alternative writ or rule nisi may be issued by a justice or judge of a court which has jurisdiction.

Conditions for use

Application of the All Writs Act requires the fulfillment of four conditions:[4]

- The absence of alternative remedies—the act is only applicable when other judicial tools are not available.

- An independent basis for jurisdiction—the act authorizes writs in aid of jurisdiction, but does not in itself create any federal subject-matter jurisdiction.

- Necessary or appropriate in aid of jurisdiction—the writ must be necessary or appropriate to the particular case.

- Usages and principles of law—the statute requires courts to issue writs "agreeable to the usages and principles of law".

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that federal administrative agencies can invoke the All Writs Act to preserve the status quo when a party within the agency's jurisdiction is about to take action that will prevent or impair the agency from carrying out its functions. In FTC v. Dean Foods Co.,[5] the Supreme Court held that a court of appeals to which an appeal could be taken against an FTC order banning a merger could properly issue a preliminary injunction under the All Writs Act while the FTC determined the merger's legality, if the need for injunctive relief was "compelling". In that case the acquired company would cease to exist since the acquiring company was about to sell all acquired milk routes, its plants and equipment, and other assets, precluding its restoration as a viable independent company if the merger were subsequently ruled illegal. This would prevent a meaningful order from being entered in the case. The Court held that the All Writs Act extends to the potential jurisdiction of an appellate court where an appeal is not then pending, but may later be perfected.

In a later similar case, the Second Circuit denied relief, because an All Writs preliminary injunction should issue only if the FTC can show that "an effective remedial order, once the merger was implemented, would otherwise be virtually impossible, thus rendering the enforcement of any final decree of divestiture futile." The Second Circuit opined that the merger probably violated the antitrust laws but did not believe that effective relief would be "virtually impossible."[6] The Supreme Court reached a similar result in a later case involving an agency's dismissal of an employee. The reason was that judicial review would not be defeated as in Dean Foods.[7]

In 1984, the D.C. Circuit relied on Dean Foods as authority for issuance of an All Writs order to compel the FCC to act on a petition that it had allegedly delayed for almost five years without acting on it.[8]

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. New York Telephone Co. 434 U.S. 159 (1977) that the act provided authority for a U.S. District Court to order a telephone company to assist law enforcement officials in installing a device on a rotary phone in order to track the phone numbers dialed on that phone, which was reasonably believed to be used in furtherance of criminal activity.[9]

Application to electronic devices

The U.S. Government has revived the All Writs Act in the 21st century, notably to gain access to password protected mobile phones in domestic terrorism and narcotics investigations.

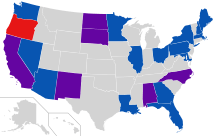

The government has been trying to use the All Writs Act since at least 2008 to force various companies to provide assistance in cracking their customers’ phones. The American Civil Liberties Union has confirmed at least 76 cases in 22 states where the government applied for an order under the All Writs Act. In addition, Apple has identified 12 pending cases in its court documents, and the ACLU has found one additional case in Massachusetts.[11]

Here are some specific examples:

On October 31, 2014, a U.S. District Court in New York authorized a writ directing a mobile phone manufacturer, whose identity was not disclosed, to assist an investigation of credit card fraud by bypassing a phone's password screen.[12]

On November 3, 2014, the Oakland Division of the U.S. Attorney's Office named Apple Inc. in papers invoking the Act, which were filed in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California. Federal law enforcement sought to require Apple to extract data from a locked iPhone 5S as part of a criminal case.[13][14]

On February 16, 2016, the Act was invoked again in an order that Apple Inc. create a special version of its iOS operating system, with certain security features removed, for Federal law enforcement officers to use as part of an investigation into the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack.[15] The head of the FBI stated that what was requested was that Apple disable the iPhone's feature which erases encrypted data on the device after ten incorrect password attempts. Apple claimed that complying with the order would make brute force password attacks trivial for anyone with access to a phone using this software.[16] Apple CEO Tim Cook in an open letter warned of the precedent that following the order would create.[17] On the same day, the Electronic Frontier Foundation announced its support for Apple's position.[18] Several public figures have joined the debate.[19]

In court filings, Apple has argued that Congress has established guidelines for what is required of private entities in such circumstances in the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 1992 (CALEA).[20] The DOJ has argued, both in October in Brooklyn and in filings on February 19, 2016, against Apple that CALEA does not apply to these cases, which involve "data at rest rather than in transit", an important distinction for determining whether CALEA applies, nor does it alter the authority granted the courts under the All Writs Act. On February 29, 2016, Magistrate Judge James Orenstein issued an order denying the government's request in its effort to decrypt an iPhone for admission as evidence.[21]

Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., a privacy advocate on the Senate Intelligence Committee, argued: "If the FBI can force Apple to build a key, you can be sure authoritarian regimes like China and Russia will turn around and force Apple to hand it over to them .... They will use that key to oppress their own people and steal U.S. trade secrets."[22]

References

- ↑ "TOPN: Table of Popular Names". Legal Information Institute.

- 1 2 "28 U.S. Code § 1651 - Writs". Legal Information Institute.

- ↑ Section 14 of the 1789 Act provided that all courts of the United States should "have power to issue writs of scire facias, habeas corpus, and all other writs not specially provided for by statute, which may be necessary for the exercise of their respective jurisdiction, and agreeable to the principles and usages of law." Findlaw, Power to Issue Writs: The Act of 1789.

- ↑ Portnoi, D. D. (March 19, 2009). "Resorting to Extraordinary Writs: How the All Writs Act Rises to Fill the Gaps in the Rights of Enemy Combatants" (PDF). New York University Law Review: 293–322. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ 384 U.S. 597 (1966).

- ↑ FTC v. PepsiCo, Inc., 477 F.2d 24 (2d Cir. 1973).

- ↑ Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61, 77-78 (1974).

- ↑ Telecommunications Research & Action Center v. FCC, 750 F.2d 70 (D.C. Cir. 1984).

- ↑ "United States v. New York Telephone Co.". Google Scholar. Supreme Court of United States. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Pagliery, Jose (March 30, 2016). "Here are the places feds are using a controversial law to unlock phones". CNN. Time Warner. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Raymundo, Oscar (March 30, 2016). "Here's a map of where Apple and Google are fighting the All Writs Act nationwide". Macworld. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ↑ "In Re Order Requiring [XXX], Inc. to Assist in the Execution of a Search Warrant ... by Unlocking a Cell Phone". Google Scholar. United States District Court, S.D. New York. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Farivar, Cyrus (December 1, 2014). "Feds want Apple's help to defeat encrypted phones, new legal case shows". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ↑ United States of America vs Apple (October 3, 2014) (“Order requiring Apple, Inc. to assist in the execution of a search warrant”). Text

- ↑ United States of America vs Apple (February 16, 2016) (“In the matter of the search of an Apple iPhone seized during the execution of a search warrant on a black Lexus IS300, California license plate 35KGD203”). Text

- ↑ Ellen Nakashima (February 17, 2016). "Apple vows to resist FBI demand to crack iPhone linked to San Bernardino attacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ Cook, Tim (February 16, 2016). "A Message to our Customers". Apple Inc. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ Opsahl, Kurt (February 16, 2016). "EFF to Support Apple in Encryption Battle". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ O'Neill, Maggie (February 19, 2016). "Apple vs. FBI: See who's taking sides". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Can an 18th-century law force Apple into hacking killer's phone?". New York Post. February 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Magistrate Judge James Orenstein's Order". The New York Times. February 29, 2016.

- ↑ Wyden, Ron. "This Isn't about One iPhone. It's About Millions of Them.". Medium.