Alexander the Great in legend

There are many legendary accounts surrounding the life of Alexander the Great, with a relatively large number deriving from his own lifetime, probably encouraged by Alexander himself.

Ancient

Prophesied conqueror

King Philip had a dream in which he took a wax seal and sealed up the womb of his wife. The seal bore the image of a lion. The seer Aristander interpreted this to mean that Olympias was pregnant, since men do not seal up what is empty, and that she would bring forth a son who would be bold and lion-like.[1] (Ephorus FGrH 70 217)

After Philip took Potidaea in 356 BC, he received word that his horse had just won at the Olympic games, and that Parmenion had defeated the Illyrians. Then he got word of the birth of Alexander. The seers told him that a son whose birth coincided with three victories would always be victorious.[2] When the young Alexander tamed the steed Bucephalus, his father noted that Macedonia would not be large enough for him.[2]

Deified Alexander

In 336, Philip sent Parmenion with an army of 10,000 men, as vanguard of a force to free the Greeks living on the western coast of Anatolia from Persian rule. The people of Eresus on the island Lesbos erected an altar to Zeus Philippios. Alexander himself was the model for the image of Apollo on coins issued by his father.[3]

When Alexander went to Egypt, he was given the title "pharaoh", which included the epithet "Son of Ra", declaring him to be the son of the sun. A story told that one night King Philip had found a huge snake in the bed next to his sleeping wife. Olympias was from Epirus and may have practiced a mystery cult that involved snake-handling.[2] The snake was said to be Zeus Ammon in disguise. After his visit to the Siwa Oasis in February 331, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father. Upon his returned to Memphis in April, he met envoys from Greece who reported that the Erythraean Sibyl had confirmed that Alexander was the son of Zeus.[3]

By 330, Alexander had started to adopt elements of Persian royal dress.[3] In 327 he introduced proskynesis a ritualized honor accorded by Persians to their rulers. This Greek soldiers resisted, as such prostrations were reserved for honoring the gods. They considered this blasphemy on Alexander's part and sure to bring condemnation from the gods.[4]

- When the Pythia refused to answer Alexander, he began to drag her to the temple. Whereupon Pythia exclaimed, You are invincible o young! (aniketos ei o pai!) (Plutarch Al. 14. 6-7)

- The one who could manage to untie the Gordian knot would become the king of Asia. (Arrian 2.3)

- Although Daniel does not refer to him by name, Alexander is the he-goat and King of Javan (Greece), coming from the west and crossing the earth without touching the ground. He charges the ram in great rage. He shatters the horns of Media and Persia and knocks the ram to the ground and tramples it.(Daniel 8:3-8).[5]

- Alexander was born on the same day the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus was burnt down. Plutarch remarked that Artemis was too preoccupied with Alexander's delivery to save her burning temple. Alexander later offered to pay for the temple's rebuilding, but the Ephesians refused on the ground that it was inappropriate for a god to dedicate offerings to other gods. (Strabo 14.1.22)

- Apelles painted Alexander holding a thunderbolt of Zeus.

- Decree of the Ionian League (uncertain date): … so that we should [pass the day on which King Antiochus] was born in … reverence [ … To each person participating in the festival] shall be given [a sum] equivalent to that given for [the sacrifice and procession for Alexander][6]

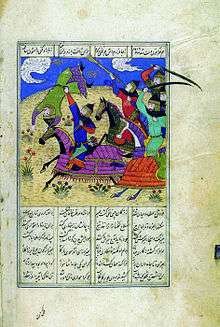

Alexander Romance

In the first centuries after Alexander's death, probably in Alexandria, a quantity of the more legendary material coalesced into a text known as the Alexander Romance, later falsely ascribed to the historian Callisthenes and therefore known as Pseudo-Callisthenes. This text underwent numerous expansions and revisions throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, exhibiting a plasticity unseen in "higher" literary forms. Latin and Syriac translations were made in Late Antiquity. From these, versions were developed in all the major languages of Europe and the Middle East, including Armenian, Georgian, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, Serbian, Slavonic, Romanian, Hungarian, German, English, Italian, and French. The "Romance" is regarded by many Western scholars as the source of the account of Alexander given in the Qur'an (Sura The Cave). It is the source of many incidents in Ferdowsi's "Shahnama". A Mongolian version is also extant.

Greek Folklore

Alexander is also a character of Greek folklore (and other regions), as the protagonist of 'apocryphal' tales of bravery. A maritime legend says that his sister is a mermaid and asks the sailors if her brother is still alive. The unsuspecting sailor who answers truthfully arouses the mermaid's wrath and his boat perishes in the waves; a sailor mindful of the circumstances will answer "He lives and reigns, and conquers the world", and the sea about his boat will immediately calm. Alexander is also a character of a standard play in the Karagiozis repertory, "Alexander the Great and the Accursed Serpent". The ancient Greek poet Adrianus composed an epic poem on the history of Alexander the Great, called the Alexandriad, which was probably still extant in the 10th century, but which is now lost to us.

Medieval

Oriental tradition

- In Shahnameh, the Persian epic, Kai Bahman's elder son Dara(b) is killed in battle with Alexander the Great, that is, Dara/Darab is identified as Darius III and which then makes Bahman a figure of the 4th century BC. In another tradition, Alexander is the son of Dara/Darab and his wife Nahid, who is described to be the daughter of "Filfus of Rûm" i.e. "Philip the Greek" (cf. Philip II of Macedon)[7][8]

- Alexander the Great was claimed as the ancestor of the Hunza rulers.[9]

- The Gates of Alexander (Caspian Gates) were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog) from invading the land to the south.

- The early Muslim scholars generally identified the Dhul-Qarnayn of the Qur'an with Alexander the Great. The Alexander legend is also believed to extend to Alexander the Great in the Qur'an, where he appears as a prophet called Dhul-Qarnayn. In the centuries that followed, Alexander the Great was often thought of by Muslims as a Prophet of Islam. Early Islamic civilization would produce its own legendary traditions about Alexander the Great, particularly in Persia. With the Muslim conquest of Persia, the Alexander Romance found its way in Persian literature—an ironic outcome considering Zoroastric Persia's hostility to the national enemy who finished the Achaemenid Empire, but was also directly responsible for centuries of Persian domination by Hellenistic "foreign rulers".[10] Islamic Persian accounts of the Alexander legend, known as the Iskandarnamah, combined the Pseudo-Callisthenes material about Alexander, some of which is found in the Qur'an, with Sasanid Persian ideas about Alexander the Great. Persian sources on the Alexander legend devised a mythical genealogy for him whereby his mother was a concubine of Darius II, making him the half-brother of the last Achaemenid shah, Darius. By the 12th century such important writers as Nezami Ganjavi were making him the subject of their epic poems. The Muslim traditions also elaborated the legend that Alexander the Great had been the companion of Aristotle and the direct student of Plato.

- The Malay language Hikayat Iskandar Zulkarnain was written about Alexander the Great as Dhul-Qarnayn and the ancestry of several Southeast Asian royal families is traced from Iskandar Zulkarnain,[11] through Raja Rajendra Chola (Raja Suran, Raja Chola) in the Malay Annals.,[12][13][14] such as the Sumatra Minangkabau royalty[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

Western tradition

Epic poems based on Alexander romance

- Alexandreis Latin

- Alexanderlied German

- Li romans d'Alixandre French

- Libro de Alexandre Spanish

- Alexanders saga Old Norse-Icelandic

- The Buik of Alexander Scottish

- Aethicus Ister (Latin) has numerous passages which deal directly with the legends of Alexander

- Azo a legendary ruler of Georgians, who had been installed by Alexander.

Apocryphal letters

- Leon of Pella wrote the book On the Gods in Egypt, based on an apocryphal letter of Alexander to his mother Olympias.

- Epistola Alexandri ad Aristotelem concerning the marvels of India.

Women and Alexander

- According to Greek Alexander Romance, Queen Thalestris of the Amazons brought 300 women to Alexander the Great, hoping to breed a race of children as strong and intelligent as he.

- According to Greek Alexander Romance, Alexander encountered the Nubian Queen Candace of Meroë

- A popular Greek legend[25][26] talks about a mermaid who lived in the Aegean for hundreds of years who was thought to be Alexander's sister Thessalonike. The legend states that Alexander, in his quest for the Fountain of Immortality, retrieved with great exertion a flask of immortal water with which he bathed his sister's hair. When Alexander died his grief-stricken sister attempted to end her life by jumping into the sea. Instead of drowning, however, she became a mermaid passing judgment on mariners throughout the centuries and across the seven seas. To the sailors who encountered her she would always pose the same question: "Is Alexander the king alive?" (Greek: Zei o vasilias Alexandros?), to which the correct answer would be "He lives, still rules, and conquers the World" (Greek: Zei kai vasilevei kai ton kosmon kyrievei!). Given this answer she would allow the ship and her crew to sail safely away in calm seas. Any other answer would transform her into the raging Gorgon, bent on sending the ship and every sailor on board to the bottom.

References

- ↑ Plutarch Al. 2.2–3

- 1 2 3 Worthington, Ian. Alexander the Great: Man and God", Routledge, 2004

- 1 2 3 Lendering, Jona. "Alexander the God", Livius.org

- ↑ Hamblin, William and Peterson, Daniel. "Alexander the Great wasn't content to be merely human", Deseret News, August 23, 2014

- ↑ Willmington's Guide to the Bible By H. L. Willmington Page 821 ISBN 978-0-8254-1874-7

- ↑ The Hellenistic world from Alexander to the Roman conquest By M. M. Austin Page 242 ISBN 0-521-29666-8

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica - Page 12 ISBN 978-0-7100-9109-3

- ↑ Alexander the Great was called "the Ruman" in Zoroastrian tradition because he came from Greek provinces which later were a part of the eastern Roman empire - The archeology of world religions By Jack Finegan Page 80 ISBN 0-415-22155-2

- ↑ Edward Frederick Knight (1893). Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the Adjoining Countries. Longmans, Green, and Company. pp. 330–.

- ↑ E.g. the Greek scholar G. G. Aperghis goes so far as to state: "Rather than considering the arrival of the Greeks as bringing something entirely new to the management of an empire, one should probably see them as apt pupils of excellent [Achaemenian] teachers. (link)"

- ↑ Balai Seni Lukis Negara (Malaysia) (1999). Seni dan nasionalisme: dulu & kini. Balai Seni Lukis Negara.

- ↑ S. Amran Tasai; Djamari; Budiono Isas (2005). Sejarah Melayu: sebagai karya sastra dan karya sejarah : sebuah antologi. Pusat Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional. p. 67. ISBN 978-979-685-524-7.

- ↑ Radzi Sapiee (2007). Berpetualang Ke Aceh: Membela Syiar Asal. Wasilah Merah Silu Enterprise. p. 69. ISBN 978-983-42031-1-5.

- ↑ Dewan bahasa. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 1980. pp. 333, 486.

- ↑ Early Modern History ISBN 981-3018-28-3 page 60

- ↑ John N. Miksic (30 September 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-9971-69-574-3.

- ↑ Marie-Sybille de Vienne (9 March 2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. NUS Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-9971-69-818-8.

- ↑ Yusoff Iskandar (1992). Pensejarahan Melayu: kajian tentang tradisi sejarah Melayu Nusantara. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan, Malaysia. p. 147. ISBN 978-983-62-3012-6.

- ↑ S. Amran Tasai; Djamari; Budiono Isas (2005). Sejarah Melayu: sebagai karya sastra dan karya sejarah : sebuah antologi. Pusat Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional. pp. 66, 67, 68. ISBN 978-979-685-524-7.

- ↑ Ismail bin Bachik (1975). Sejarah kesusasteraan Melayu tradisional dan moden: untuk peperiksaan sijil tinggi persekolahan, GCE (Singapura) dan mahasiswa tahun pertama di universiti. Syarikat Nusantara. p. 40.

- ↑ Buyong bin Adil (Haji.) (1972). Sejarah Singapura: rujukan khas mengenai peristiwa2 sebelum tahun 1824. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. p. 14.

- ↑ Dewan bahasa. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 1967. p. 541.

- ↑ Radzi Sapiee (2007). Berpetualang Ke Aceh: Membela Syiar Asal. Wasilah Merah Silu Enterprise. p. 69. ISBN 978-983-42031-1-5.

- ↑ Soeroto (Drs.). Indonesia ditengah-tengah dunia dari abad keabad: peladjaran sedjarah untuk sekolah menengah.

- ↑ Mermaids and Ikons: A Greek Summer (1978) page 73 by Gwendolyn MacEwen ISBN 978-0-88784-062-3

- ↑ Folktales from Greece Page 96 ISBN 1-56308-908-4

See also

- Mythography

- Historical Alexander the Great

- Alexander the Great in the Qur'an

- Cultural depictions of Alexander the Great