Alcoholic polyneuropathy

| Alcoholic polyneuropathy | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | neurology |

| ICD-10 | G62.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 357.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 9850 |

| MedlinePlus | 000714 |

| eMedicine | article/315159 |

| MeSH | D020269 |

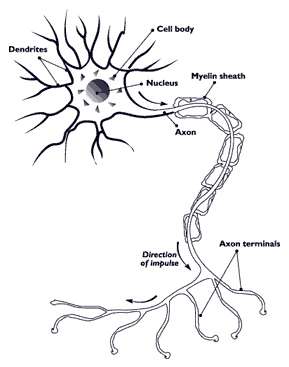

Alcoholic polyneuropathy (A.K.A alcohol leg) is a neurological disorder in which multiple peripheral nerves throughout the body malfunction simultaneously. It is defined by axonal degeneration in neurons of both the sensory and motor systems and initially occurs at the distal ends of the longest axons in the body. This nerve damage causes an individual to experience pain and motor weakness, first in the feet and hands and then progressing centrally. Alcoholic polyneuropathy is caused primarily by chronic alcoholism; however, vitamin deficiencies are also known to contribute to its development. This disease typically occurs in chronic alcoholics who have some sort of nutritional deficiency. Treatment may involve nutritional supplementation, pain management, abstaining from alcohol.

Signs and symptoms

Alcoholic polyneuropathy usually has a gradual onset over months or even years although axonal degeneration often begins before an individual experiences any symptoms.[1] An early warning sign (prodrome) of the possibility of developing alcoholic polyneuropathy, specially in a chronic alcoholic, would be weight loss because this usually signifies a nutritional deficiency that can lead to the development of the disease.[2]

The disease typically involves sensory and motor loss, as well as painful physical perceptions (paresthesias), though all sensory modalities may be involved.[3] Symptoms that affect the sensory and motor systems seem to develop symmetrically. For example, if the right foot is affected, the left foot is affected simultaneously or soon becomes affected.[2] In most cases, the legs are affected first, followed by the arms. The hands usually become involved when the symptoms reach above the ankle.[3] This is called a stocking-and-glove pattern of sensory disturbances.[4]

Polyneuropathy spans a large range of severity. Some cases are seemingly asymptomatic and may only be recognized on careful examination. The most severe cases may cause profound physical disability.[2]

Sensory

Common manifestations of sensory issues include numbness or painful sensations in the arms and legs, abnormal sensations like “pins and needles,” and heat intolerance.[5] Pain experienced by individuals depends on the severity of the polyneuropathy. It may be dull and constant in some individuals while being sharp and lancinating in others.[4] In many subjects, tenderness is seen upon the palpitation of muscles in the feet and legs.[2] Certain people may also feel cramping sensations in the muscles affected and others say there is a burning sensation in their feet and calves.[4]

Motor

Sensory symptoms are gradually followed by motor symptoms.[3] Motor symptoms may include muscle cramps and weakness, erectile dysfunction in men, problems urinating, constipation, and diarrhea.[3] Individuals also may experience muscle wasting and decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes.[2] Some people may experience frequent falls and gait unsteadiness due to ataxia. This ataxia may be caused by cerebellar degeneration, sensory ataxia, or distal muscle weakness.[4] Over time, alcoholic polyneuropathy may also cause difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), speech impairment (disarthria), muscle spasms, and muscle atrophy.[5]

In addition to alcoholic polyneuropathy, the individual may also show other related disorders such as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and cerebellar degeneration that result from alcoholism-related nutritional disorders.[2]

Causes

The general cause of this disease is prolonged and heavy consumption of alcohol accompanied by a nutritional deficiency. There is some debate over whether the main cause is the direct toxic effect of alcohol itself or whether the disease is a result of alcoholism-related malnutrition.[2]

Frequently alcoholics have disrupted social links in their lives and have an irregular lifestyle. This may cause an alcoholic to change their eating habits including more missed meals and a poor dietary balance.[6] Alcoholism may also result in loss of appetite, alcoholic gastritis, and vomiting, which decrease food intake. Alcohol abuse damages the lining of the gastrointestinal system and reduces absorption of nutrients that are taken in.[7] The combination of all of them may result in a nutritional deficiency that is linked to the development of alcoholic polyneuropathy.[6]

There is evidence that providing individuals with adequate vitamins improves symptoms despite continued alcohol intake, indicating that vitamin deficiency may be a major factor in the development and progression of alcoholic polyneuropathy.[1] In experimental models of alcoholic polyneuropathy utilizing rats and monkeys has not resulted in convincing evidence that proper nutritional intake along with alcohol results in polyneuropathy.[2]

In addition, the consumption of alcohol may lead to the buildup of certain toxins in the body. For example, in the process of breaking down alcohol, the body produces acetaldehyde, which can accumulate to toxic levels in alcoholics. This suggests that there is a possibility ethanol (or its metabolites) may cause alcoholic polyneuropathy.[4] There is evidence that polyneuropathy is also prevalent in well nourished alcoholics, supporting the idea that there is a direct toxic effect of alcohol.

Many of the studies conducted that observe alcoholic polyneuropathy in patients are often criticized for their criteria used to assess nutritional deficiency in the subjects because they may not have completely ruled out the possibility of a nutritional deficiency in the genesis of the polyneuropathy.[2] Many researchers favor the nutritional origin of this disease, but the possibility of alcohol having a toxic effect on the peripheral nerves has not been completely ruled out.[2]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of alcoholic polyneuropathy is an area of current research. Damage to the nervous system takes place before symptoms appear in individuals, beginning with segmental thinning and loss of myelin on the peripheral ends of the longest nerves. Segmental thinning is the demyelination of axons in small sections at a time. This occurrence increases leakage of an action potential current down the axon, so it is weakest at the peripheral end. Decrease in current causes further thinning of myelin.[1]

In most cases, individuals with alcoholic polyneuropathy have some degree of nutritional deficiency. Alcohol, a carbohydrate, increases the metabolic demand for thiamine (vitamin B1) because of its role in the metabolism of glucose. Thiamine levels are usually low in alcoholics due to their decreased nutritional intake. In addition, alcohol interferes with intestinal absorption of thiamine, thereby further decreasing thiamine levels in the body.[8] Thiamine is important in three reactions in the metabolism of glucose: the decarboxylation of pyruvic acid, d-ketoglutaric acid, and transketolase. A lack of thiamine in the cells may therefore prevent neurons from maintaining necessary adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels as a result of impaired glycolosis. Thiamine deficiency alone could explain the impaired nerve conduction in those with alcoholic polyneuropathy, but other factors likely play a part.[1]

The metabolic effects of liver damage associated with alcoholism may also contribute to the development of alcoholic polyneuropathy. Normal products of the liver, such as lipoic acid, may be deficient in alcoholics. This deficiency would also disrupt glycolosis and alter metabolism, transport, storage, and activation of essential nutrients.[1]

The malnutrition many alcoholics suffer deprives them of important cofactors for the oxidative metabolism of glucose. Neural tissues depend on this process for energy, and disruption of the cycle would impair cell growth and function. Schwann cells produce myelin that wraps around the sensory and motor nerve axons to enhance action potential conduction in the periphery. An energy deficiency in Schwann cells would account for the disappearance of myelin on peripheral nerves, which may result in damage to axons or loss of nerve function altogether. In peripheral nerves, oxidative enzyme activity is most concentrated around the nodes of Ranvier, making these locations most vulnerable to cofactor deprivation. Lacking essential cofactors reduces myelin impedance, increases current leakage, and slows signal transmission. Disruptions in conductance first affect the peripheral ends of the longest and largest peripheral nerve fibers because they suffer most from decreased action potential propagation. Thus, neural deterioration occurs in an accelerating cycle: myelin damage reduces conductance, and reduced conductance contributes to myelin degradation. The slowed conduction of action potentials in axons causes segmental demyelination extending proximally; this is also known as retrograde degeneration.[1]

Acetaldehyde is toxic to peripheral nerves. There are increased levels of acetaldehyde produced during ethanol metabolism. If the acetaldehyde is not metabolized quickly the nerves may be affected by the accumulation of acetaldehyde to toxic levels.[4][9]

Diagnosis

Alcoholic polyneuropathy is very similar to other axonal degenerative polyneuropathies and therefore can be difficult to diagnose. When alcoholics have sensorimotor polyneuropathy as well as a nutritional deficiency, a diagnosis of alcoholic polyneuropathy is often reached.[2][10]

To confirm the diagnosis, a physician must rule out other causes of similar clinical syndromes. Other neuropathies can be differentiated on the basis of typical clinical or laboratory features.[10] Differential diagnoses to alcoholic polyneuropathy include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, beriberi, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy, Guillain Barre Syndrome, diabetic neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex and post-polio syndrome.[3]

To clarify the diagnosis, medical workup most commonly involves laboratory tests, though, in some cases, imaging, nerve conduction studies, electromyography, and vibrometer testing may also be used.[3]

A number of tests may be used to rule out other causes of peripheral neuropathy. One of the first presenting symptoms of diabetes mellitus may be peripheral neuropathy, and hemoglobin A1C can be used to estimate average blood glucose levels. Elevated blood creatinine levels may indicate renal insufficiency and may also be a cause of peripheral neuropathy. A heavy metal toxicity screen should also be used to exclude lead toxicity as a cause of neuropathy.[3]

Alcoholism is normally associated with nutritional deficiencies, which may contribute to the development of alcoholic polyneuropathy. Thiamine, vitamin B-12, and folic acid are vitamins that play an essential role in the peripheral and central nervous system and should be among the first analyzed in laboratory tests.[3] It has been difficult to assess thiamine status in individuals due to difficulties in developing a method to directly assay thiamine in the blood and urine.[2] A liver function test may also be ordered, as alcoholic consumption may cause an increase in liver enzyme levels.[3]

Management

Although there is no known cure for alcoholic polyneuropathy, there are a number of treatments that can control symptoms and promote independence. Physical therapy is beneficial for strength training of weakened muscles, as well as for gait and balance training.[3]

Nutrition

To best manage symptoms, refraining from consuming alcohol is essential. Abstinence from alcohol encourages proper diet and helps prevent progression or recurrence of the neuropathy.[10] Once an individual stops consuming alcohol it is important to make sure they understand that substantial recovery usually isn't seen for a few months. Some subjective improvement may appear right away, but this is usually due to the overall benefits of alcohol detoxification.[8] If alcohol consumption continues, vitamin supplementation alone is not enough to improve the symptoms of most individuals.[4]

Nutritional therapy with parenteral multivitamins is beneficial to implement until the person can maintain adequate nutritional intake.[2] Treatments also include vitamin supplementation (especially thiamine). In more severe cases of nutritional deficiency 320 mg/day of benfotiamine for 4 weeks followed by 120 mg/day for 4 more weeks may be prescribed in an effort to return thiamine levels to normal.[4]

Pain

Painful dysesthesias caused by alcoholic polyneuropathy can be treated by using gabapentin or amitriptyline in combination with over-the-counter pain medications, such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or acetaminophen. Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, or carbamazepine may help stabbing pains and have central and peripheral anticholinergic and sedative effects. These agents have central effects on pain transmission and block the active reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin.[3][5]

Anticonvulsant drugs like gabapentin block the active reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin and have properties that relieve neuropathic pain. However, these drugs take a few weeks to become effective and are rarely used in the treatment of acute pain.[3]

Topical analgesics like capsaicin may also relieve minor aches and pains of muscles and joints.[3]

Prognosis

It is difficult to assess the prognosis of a patient because it is hard to convince chronic alcoholics to abstain from drinking alcohol completely. It has been shown that a good prognosis may be given for mild neuropathy if the alcoholic has abstained from drinking for 3–5 years.[9] During the early stages of the disease the damage appears reversible when people take adequate amounts of vitamins, such as thiamine.[1] If the polyneuropathy is mild, the individual normally experiences a significant improvement and symptoms may be completely eliminated within weeks to months after proper nutrition is established.[2] When those people diagnosed with alcohol polyneuropathy experience a recovery, it is presumed to result from regeneration and collateral sprouting of the damaged axons.[4]

As the disease progresses, the damage may become permanent. In severe cases of thiamine deficiency, a few of the positive symptoms (including neuropathic pain) may persist indefinitely.[9] Even after the restoration of a balanced nutritional intake, those patients with severe or chronic polyneuropathy may experience lifelong residual symptoms.[2] Alcoholic polyneuropathy is not life-threatening but may significantly affect one's quality of life. Effects of the disease range from mild discomfort to severe disability.[5]

Epidemiology

The rate of incidence of alcoholic polyneuropathy involving sensory and motor polyneuropathy varies from 10% to 50% of alcoholics depending on the subject selection and diagnostic criteria. If electrodiagnostic criteria is used, alcoholic polyneuropathy may be found in up to 90% of individuals being assessed.[4] The distribution and severity the disease depends on regional dietary habits, individual drinking habits, as well as an individual’s genetics.[9] Large studies have been conducted and show that alcoholic polyneuropathy severity and incidence correlates best with the total lifetime consumption of alcohol. Factors such as nutritional intake, age, or other medical conditions are correlate in lesser degrees.[8] For unknown reasons, alcoholic polyneuropathy has a high incidence in women.[4]

Certain alcoholic beverages can also contain congeners that may also be bioactive; therefore, the consumption of varying alcoholic beverages may result in different health consequences.[9] An individual’s nutritional intake also plays a role in the development of this disease. Depending on the specific dietary habits, they may have a deficiency of one or more of the following: thiamine (vitamin B1), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), pantothenic acid and biotin, vitamin B12, folic acid, niacin (vitamin B3), and vitamin A.[5]

Acetaldehyde

It is also thought there is perhaps a genetic predisposition for some alcoholics that results in increased frequency of alcoholic polyneuropathy in certain ethnic groups. During the body’s processing of alcohol, ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde mainly by alcohol dehydrogenase; acetaldehyde is then oxidized to acetate mainly by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). ALDH2 is an isozyme of ALDH and ALDH2 has a polymorphism (ALDH2*2, Glu487Lys) that makes ADLH2 inactive; this allele is more prevalent among Southeast and East Asians and results in a failure to quickly metabolize acetaldehyde. The neurotoxicity resulting from the accumulation of acetaldehyde may play a role in the pathogenesis of alcoholic polyneuropathy.[4][9]

History

The first description of symptoms associated with alcoholic polyneuropathy were recorded by John C. Lettsome in 1787 when he noted hyperesthesia and paralysis in legs more than arms of patients.[1] Jackson has also been credited with describing polyneuropathy in chronic alcoholics in 1822. The clinical title of alcoholic polyneuropathy was widely recognized by the late nineteenth century. It was thought that the polyneuropathy was a direct result of the toxic effect alcohol had on peripheral nerves when used excessively. In 1928, George C. Shattuck argued that the polyneuropathy resulted from a vitamin B deficiency commonly found in alcoholics and he claimed that alcoholic polyneuropathy should be related to beriberi. This debate continues today over what exactly causes this disease, some argue it is just the alcohol toxicity, others claim the vitamin deficiencies are to blame and still others say it is some combination of the two.[2]

Research directions

The mechanism of axonal degeneration has not been clarified and is an area of continuing research on alcoholic polyneuropathy.[9]

Further research is looking at the effect an alcoholics’ consumption and choice of alcoholic beverage on their development of alcoholic polyneuropathy. Some beverages may include more nutrients than others (such as thiamine), but the effects of this with regards to helping with a nutritional deficiency in alcoholics is yet unknown.[7]

There is still controversy about the reasons for the development of alcoholic polyneuropathy. Some argue it is a direct result of alcohol's toxic effect on the nerves, but others say factors such as a nutritional deficiency or chronic liver disease may play a role in the development as well. This debate is ongoing and research is continuing in an effort to discover the real cause of alcoholic polyneuropathy.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mawdsley, C.; Mayer, R. F. (1965). "Nerve Conduction in Alcoholic Polyneuropathy". Brain; a journal of neurology. 88 (2): 335–356. doi:10.1093/brain/88.2.335.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Aminoff, Michael J.; Brown, William A.; Bolton, Charles Francis (2002). Neuromuscular function and disease: basic, clinical and electrodiagnostic aspects. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. pp. 1112–1115. ISBN 0-7216-8922-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Laker, SR; Sullivan, WJ. "Alcoholic Neuropathy". eMedicine. Medscape. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Roongroj Bhidayasiri; Lisak, Robert P.; Daniel Truong; Carroll, William K. (2009). International Neurology. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 413–414. ISBN 1-4051-5738-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 MedlinePlus; National Library of Medicine (20 February 2011). "Alcoholic Polyneuropathy". National Institute of Health.

- 1 2 Preedy, Victor R.; Watson, Ronald R. (2004). Nutrition and alcohol: linking nutrient interactions and dietary intake. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 7–13. ISBN 0-8493-1680-4.

- 1 2 Vittadini G, Buonocore M, Colli G, Terzi M, Fonte R, Biscaldi G (2001). "Alcoholic Polyneuropathy: A Clinical and Epidemiological Study". Oxford Journals. 36 (5): 393–400. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.5.393.

- 1 2 3 4 Cornblath, David R.; Jerry R. Mendell; Kissel, John T. (2001). Diagnosis and management of peripheral nerve disorders. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 332–334. ISBN 0-19-513301-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Koike, H; Sobue, G (2006). "Alcoholic Neuropathy". Current Opinion in Neurology. 19 (5): 481–486. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000245371.89941.eb. ISSN 1350-7540. PMID 16969158.

- 1 2 3 Shields, Jr., RW (Mar–Apr 1985). "Alcoholic Polyneuropathy". Muscle & Nerve. 8 (3): 183–187. doi:10.1002/mus.880080302.