Agnone

| Agnone | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Città di Agnone | ||

| ||

| ||

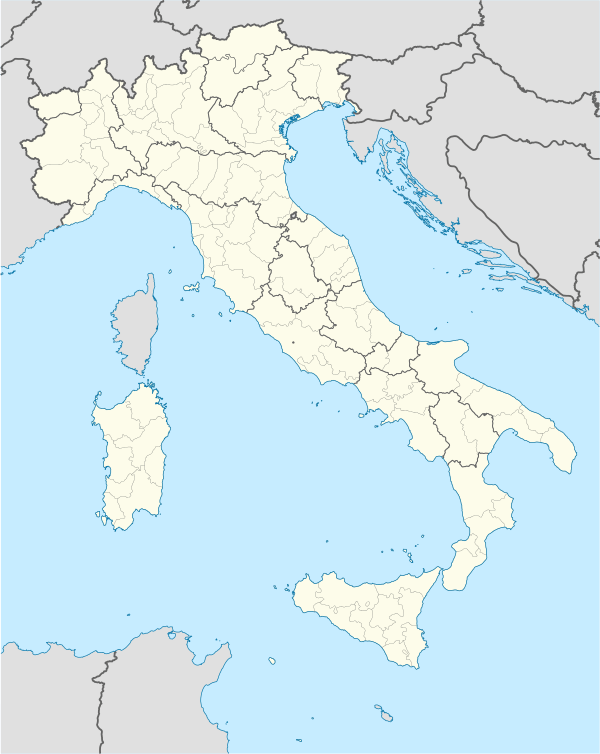

Agnone Location of Agnone in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 41°48′36″N 14°22′44″E / 41.81000°N 14.37889°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Molise | |

| Province / Metropolitan city | Isernia (IS) | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Lorenzo Marcovecchio | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 96 km2 (37 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 850 m (2,790 ft) | |

| Population (31 December 2014) | ||

| • Total | 5,125 | |

| • Density | 53/km2 (140/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Agnonesi | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 86081 | |

| Dialing code | 0865 | |

| Patron saint | San Cristanziano | |

| Website | Official website | |

Agnone is a comune in the province of Isernia, in the Molise region of southern Italy. Agnone is known for the manufacturing of bells by the Marinelli Bell Foundry. It is some 25 kilometres (16 mi) northwest of Campobasso. The town of Agnone proper is complemented with other populated centers like Fontesambuco, Villa Canale and Rigaini.

History

Samnites

The pre-Roman Samnites consisted of several distinct tribes who existed in Samnium which was a wholly inland district of south central Italy. The Pentri tribe of the Samnites was the most powerful and based in Bovianium, which was a city some 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of present Agnone. Agnone is in the center of important archaeological vestiges of the old Oscan-Samnite civilization and is sometimes called “the Athens of the Sannio” due to the large number of ancient ruins of the Samnitic culture.[1] According to the tradition, the name of Agnone derives from the old city of Aquilonia that was destroyed by the Romans.[1] The Samnited were annihilated at the time of Sulla by the consuls Carvilius and Lucius Papirius Cursor in 293 B.C. Papirius, after making himself master of Aquilonia, which he burnt to the ground, proceeded to besiege Saepinum, on his way to Bovianum.

. The Samnites spoke Oscan and knowledge of the Oscan language is furnished on this small bronze tablet, which was discovered at Fonte di Romito, between Capracotta and Agnone in 1848. The place of discovery was near the river Sagrus or Sangro; this inscription is an example of the most southerly dialect of the Samnite language. The tablet speaks of a series of dedications to different deities or holy beings[3]

Romans

During the Roman Period, Christianity was spread to Molise. Agnone appears on Roman maps under different regions at various times as Aprutium, Picenum, Sabina et Samnium, Flaminia et Picenum and/or Campania et Samnium. The Roman penchant for building seems to have passed Agnone over as Samnitic architecture still prevailed.

Medieval

Agnone was an important center during the rule of the Lombards, but then was left decaying in the centuries immediately preceding 1000, while the Verrino Valley and surrounding hills became a place of hermitages, monasteries and small agricultural colonies. In 1139 the powerful Borrello family, supported by soldiers of fortune from Venice, probably originating from colonies Dalmatian of the "Serenissima" took control of Agnone.[4] The importance of Agnone grew during the Angevin and also in the Aragonese reigns to the point that during the reign of the Bourbons of the Two Sicilies, the city was among the 56 royal towns, that reported directly to the King, and was free from any other type of feudal subjection. Joseph Bonaparte decided to create the region Molise, that was to exclude Agnone, but during the reign of Joachim Murat, the elders of Agnone asked and obtained the transition to Molise, basing the request on the geographical difficulties of the links to Abruzzo, and hoping to rise to a new role for the small region. During this period, the natural resources surrounding Agnone impacted its economy where skilled craftsmen produced gold jewelry, copperware, watches, and bells.

Post-Unification

Agnone would suffer a significant decline in years following the Unification of Italy in the 1860s. In 1884 the local newspaper L'Aquilonia reviewed the causes of emigration of peasants from Agnone and concluded that the two main factors were excessive taxes on consumers' goods and usurious interest rates that at times surpassed 20 percent in the town.[5] The peasants were arrested for stealing the crops of the galantuomini ("gallant men" or ruling class), and a particularly frequent crime was the illegal cutting of timber on the town commons. In 1863, for example, the authorities actually prosecuted 624 cases of illegal felling of trees.

Consequently, when by the 1870s, owing to improvements in sea travel, a lowering of fares, and the expansive nature of the economies of both the United States and the Rio de la Plata region of southern South America, transatlantic emigration became a viable alternative, the lower classes of Agnone were, out of a sense of desperation, prime candidates. Politically alienated by decades of unfulfilled promises of land reform, mired in endemic poverty, dependent on a rapacious class of galantuomini for what was, by any yardstick, a meager existence, the peasantry was further squeezed by relentless population increase throughout the first seven decades of the 19th century.[6]

World War II to present

When Benito Mussolini's fascist regime came to power, they effectively put a stop to Italy's out migration. During the Fascist era, Agnone was the site of exile for many opponents of the ruling party, including Don Raimondo Viale, protagonist of "The Just Priest" by Nuto Revelli. The Germans sat up a concentration camp in Molise for gypsies where Father Viale tried to help them. The War would finally reach Agnone in December 1943, as the Allied Forces would land on Italy's Adriatic coast and make their way northward and westward to Rome. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division would drive the Germans and Fascists out of Molise, and on 2 and 3 December, the West Nova Scotia Regiment would billet in Agnone during the Ortona offensive.[7]

After the war, Agnone's out migration issues continued, although more for reasons of economic availability. As international emigration declined, southern Italians migrated to industrial northern Italy for more promising economic prospects.[8] Presently, Agnone's population is still declining. As Molise is starting to find recognition as a tourist destination, Agnone is marketing itself on the agritourism market and for its unique Pre-Roman and Medieval architecture.[8]

Main sights

Medieval sights

The town's medieval-style architecture is reflected in its nineteen churches, including the Church of San Marco, with a large Renaissance portal embellished by a copper lion. In the 11th century Odorisio and Gualtiero Borrello introduced the cult of Saint Mark and brought artists from Venice to decorate their homes with Saint Mark's lion. This church is adorned with great artwork including: rich altars, a painting of a Holy Family and Saints by Luca Giordano; an obstensory in gilded copper and enamel, by Giovanni da Agnone, a disciple of Nicola da Guardiagrele. The church of Sant'Antonio Abate has a Romanesque portal and a 17th-century bell tower, and on the vault inside a giant fresco by Francesco Palumbo. Sant'Emidio has a 12th-century portal and rich works of art including wooden painted statues that are taken out on Good Thursday and Friday for a re-enactment of the Last Supper. The church of Corso Garibaldi, is sided by ancient houses with stone lions near the doors (the lion is on Agnone coat of arms), ancient artisans' workshops, Apollonio house and Nuonno house. Church of San Francesco displays a giant round window over the portal, dated 1330. Inside, the Final Judgment on the vault is painted by Gambora.

The Church of San Nicola has a peculiar bell tower coated with yellow and green ceramic tiles. It is due to Agnone’s craftsmen and medieval architecture that the town adopted the nickname Città d'Arte (City of Art) which the town uses on a promotional basis.[9]

Pontificia Fonderia Marinelli

The Pontificia Fonderia Marinelli (the Marinelli Pontifical Foundry) is an ancient factory of bells which has been operating in Agnone for nearly a millennium. It ranks as one of the oldest companies in the world, where the Marinelli family has run the foundry for the last 1000 years.

This factory has a museum, where bells of almost a thousand years of antiquity to more recent others are displayed. It is also possible to observe the artisan process of the manufacturing of bells. The factory was visited by the Pope John Paul II in 1995 as many of the foundry’s bells can be found at the Vatican.

Geography

Agnone lies on a rocky spear in the mountainous regions of Molise (Alto Molise). Farms and country houses surround the city at elevations varying from the 1,386 metres (4,547 ft) above sea level at Monte Castelbarone to 370 metres (1,210 ft) of the Verrino River bed. The Sangro River also passes by Agnone.

Its geographic position has been described as "The natural capital of the Alto Molise". Its territorial extension covers 9,630 hectares (23,800 acres) made up of forests, pastures and agriculture land.

Culture

On Christmas Eve Agnone holds the "Carnevale Agnonese", including the Ndocciata, which is a huge torchlight parade of thousands of handmade, wooden torches made into nine different quarters ("borgate"), accompanied by the sound of bagpipes, to the Piazza Plebiscito where a brotherhood bonfire is lit.

The Fiera delle Arti e Mestieri Antichi (Arts and Antique Crafts Fair) is held 17 to 19 August where a large area of the old town home to artisans, display their works. Artisan's crafts at the fair generally include goldsmiths, tinkers, tanners, wrought-iron, lace and embroidery.

Notable people

- Saint Francis Caracciolo: Confessor, co-founder of the Congregation of the Minor Clerks Regular, born Abruzzo, Italy, 1563; died Agnone, Italy, 1608. He went to Naples in 1585 to study theology, and was ordained in 1587. He collaborated with John Augustine Adorno in drawing up rules for the Congregation, which was approved by Pope Sixtus V, 1588. Chosen general at Naples, 1593, he established houses in Rome, Madrid, Valladolid, and Alcala. Relics at Naples and San Lorenzo in Lucina, Rome. Canonized, 1807. Feast, Roman Calendar, 4 June.

- Maria Jonata, poet of the 15th century, author of the poem El Giardeno.

- Marcantonio Gualtieri (16th-17th century), a medicine man who cured many nobles of the time and who fought the rampant scourge of the plague

- Matteo di Agnone (Prospero Lolli) religious Capuchin (1563–1616).

- Stefano di Stefano, born in Agnone in 1665, man of law and literature, author of the work The Region Pastorale (Naples 1731).

- Baldassare Labanca (1829–1913) was University professor to the University of Padua, Pisa and Rome. Author of numerous publications on philosophy and religion,

- Giovanni Batiste Di Menna, former-friar Capuchin that abandoned Catholicism to become an evangelical preacher to London in the 19th century.

- Don Raimondo Viale, protagonist of "The Just Priest"

References

- 1 2 Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. William Smith, LLD. London. Walton and Maberly, Upper Gower Street and Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row; John Murray, Albemarle Street. 1854.

- ↑ British Museum Collection

- ↑ A Critical and Historical Introduction to the Ethnography of ancient Italy, by John William Donaldson, London, John W. Parker and Son, 1852.

- ↑ Italy, by Dana Facaros, Michael Pauls 2004

- ↑ Emigration in a south Italian town: an anthropological history. William A. Douglass 1984

- ↑ Emigration in a south Italian town: an anthropological history . William A. Douglass 1984

- ↑ Ortona: Canada's Epic World War II Battle By Mark Zuehlke

- 1 2 The South Italian Family: a Critique. Journal of Family History 1980; 5; 338 William A. Douglass

- ↑ The Palladino Family in America: Descendants of Pietrantonio Palladino. Peter August Hoetjes