Acromyrmex

| Acromyrmex | |

|---|---|

| |

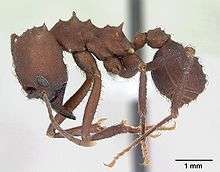

| A. octospinosus worker carrying a leaf | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Genus: | Acromyrmex Mayr 1865 |

| Type species | |

| Formica hystrix Latreille, 1802 | |

| Diversity[1] | |

| 32 species | |

Acromyrmex is a genus of New World ants of the subfamily Myrmicinae. This genus is found in South America and parts of Central America and the Caribbean Islands, and contains 31 known species. Commonly known as "leafcutter ants" they comprise one of the two genera of advanced attines within the tribe Attini, along with Atta.

Anatomy

Acromyrmex species' hard outer covering, the exoskeleton or cuticle, functions as armour, protection against dangerous solar waves, an attachment base for internal muscles, and to prevent water loss. It is divided into three main parts; the head, thorax, and abdomen. A small segment between the thorax and abdomen, the petiole, is split into two nodes in Acromyrmex species.

The antennae are the most important sense organs Acromyrmex species possess, and are jointed so the ant can extend them forward to investigate an object. It can retract them back over its head when in a dangerous situation, for example, a fight. Acromyrmex species have eyes, but their eyesight is very poor. Like all insects, the eye is compound, meaning it is made up of many eyelets called ommatidia, with the number of these eyelets varies according to species. Male ants tend to have more ommatadia than other castes. The ocelli, which are generally found on top of the heads of queens, are thought to aid aerial navigation by sunlight.

Acromyrmex is dark red in color. In addition to the standard ant anatomy, the back of the thorax has a series of spines which help it maneuver material such as leaf fragments on its back.

Acromyrmex can be identified from the closely related Atta genus of leafcutter ants by their having four pairs of spines and a rough exoskeleton on the upper surface of the thorax compared to three pairs of spines and a smooth exoskeleton in Atta.

Much of the inside of the Acromyrmex head is occupied by the muscles that close the jaws; the muscles that open the jaws are much smaller. The brain, though tiny, is a very complex organ, and allows Acromyrmex to learn and react to its surroundings. It can remember colony odour, navigation, and where it has placed a certain object.

The heart is a long, tubular organ running the entire length of the body, from the brain to the tip of the abdomen. It has valves within it that prevent blood from flowing the wrong way. The fluids bathing the internal organs is circulated by the heart; these fluids then filter through the organs and tissues. The pharynx, which is part of the gut, controlled by six muscles, pumps food into the oesophagus. Debris in the food, such as soil, is filtered before it enters the oesophagus and is collected in a tiny trap, the infrabuccal pocket. When this pocket becomes full, the Acromyrmex ant empties it into an area within or outside the nest designated as a waste-products area.

Several glands in the head secrete various substances, such as those responsible for the digestion of food. Another gland within the head produces digestive and, in some species, alarm chemicals; these chemicals are used to alert nearby ants of impending danger, and any ant that detects this alarm will automatically go into "battle mode". If an ant is crushed, a huge blast of this chemical is released, causing the entire colony to go into "battle mode".

The thorax contains muscles to operate the legs and wings and the nerve cells to co-ordinate their movements; also contained in this part of the body is the heart and oesophagus.

The abdomen contains the stomachs, poison glands, ovaries in the queen, and the Dufour's gland, among other things. Acromyrmex ants have two "stomachs", including a dry, social stomach in which they can store food and later regurgitate to larvae, the queen and other ants. This is separated from the stomach proper by a small valve; once food enters the second stomach, it becomes contaminated with gastric juices and cannot be regurgitated. The exact function of the Dufour's gland is unknown, but is thought to be involved in the release of the chemicals used in the production of odour trails, which the ants use to recruit nest mates to a food source. It may also produce sex-attractant chemicals.

Ecology

Reproduction

Winged females and males leave their respective nests en masse and engage in a nuptial flight known as the revoada. Each female mates with multiple males to collect the 300 million sperm she needs to set up a colony.[2]

Once on the ground, the female loses her wings and searches for a suitable underground lair in which to found her colony. The success rate of these young queens is very low and only 2.5% will go on to establish a long-lived colony. Before leaving their parent colonies, winged females take a small section of fungus into their infrabucchal pouches to 'seed' the fungus gardens of incipient colonies, cutting and collecting the first few sections of leaf themselves.

Colony hierarchy

A mature leafcutter colony can contain more than 8 million ants (the maximum size of the colony varies between species), mostly sterile female workers. They are divided into castes, based mostly on size, that perform different functions. Acromyrmex ants exhibit a high degree of biological polymorphism, four castes being present in established colonies - minims (or "garden ants"), minors, mediae, and majors. Majors are also known as soldiers or dinergates. Each caste has a specific function within the colony. Acromyrmex ants are less polymorphic than the other genus of leafcutter ants Atta, meaning comparatively less difference in size exists from the smallest to largest types of Acromymex. The high degree of polymorphism in this genus is also suggestive of its high degree of advancement.

Ant-fungus mutualism

Like Atta, Acromyrmex societies are based on an ant-fungus mutualism, and different species use different species of fungus, but all of the fungi the ants use are members of the genus Leucocoprinus. The ants actively cultivate their fungus on a medium of masticated leaf tissue. This is the sole food of the queen and other colony members that remain in the nest. The mediae also gain subsistence from plant sap they ingest whilst physically cutting out sections of leaf from a variety of plants.

This mutualistic relationship is further augmented by another symbiotic partner, a bacterium that grows on the ants and secretes chemicals; essentially, the ants use portable antimicrobials. Leafcutter ants are sensitive enough to adapt to the fungus' reaction to different plant material, apparently detecting chemical signals from it. If a particular type of leaf is toxic to the fungus, the colony will no longer collect it. The only two other groups of insects that have evolved fungus-based agriculture are ambrosia beetles and termites. The fungus cultivated by the adults is used to feed the ant larvae and the adult ants feed on the leaf sap. The fungus needs the ants to stay alive, and the larvae need the fungus to stay alive.[3]

In addition to feeding the fungal garden with foraged food, mainly consisting of leaves, it is protected from Escovopsis by the antibiotic secretions of Actinobacteria (genus Pseudonocardia). This mutualistic microorganism lives in the metapleural glands of the ants.[4] Actinobacteria are responsible for producing the majority of the world's antibiotics today.

Waste management

Leafcutter ants have very specific roles for taking care of the fungal garden and dumping the refuse. Waste management is a key role for each colony's longevity. The necrotrophic parasite Escovopsis of the fungal cultivar threatens the ants' food source, and is a constant danger to the ants. The waste transporters and waste-heap workers are the older, more dispensable ants, ensuring the healthier and younger leafcutter ants can work on the fungal garden. Waste transporters take the waste, which consists of used substrate and discarded fungus, to the waste heap. Once dropped off at the refuse dump, heap workers organise the waste and constantly shuffle it around to aid decomposition.

Foraging behaviour

Acromyrmex has evolved to change food plants constantly, preventing a colony from completely stripping off leaves and thereby killing trees, thus avoiding negative biological feedback on account of their sheer numbers. However, this does not diminish the huge quantities of foliage they harvest. Once foraging workers locate a resource in their environment, they lay down a pheromone trail as they return to the colony. Other workers then follow the pheromone trail to the resource. As more workers return to the nest, laying down pheremones, the stronger the trail becomes. The strength to which workers adhere to the trail (trail fidelity) depends mostly on environmental factors, such as the quality of the resource.

Interactions with humans

In some parts of their range, Acromyrmex species can be quite a nuisance to humans, defoliating crops and damaging roads and farmland with their nest-making activities.[2] For example, Acromyrmex octospinosus ants harvest huge quantities of foliage, so they have become agricultural pests on the various Caribbean islands where they have been introduced, such as Guadeloupe.

In Central America, leafcutter ants are referred to as "wee wee" ants, though not based on their size. They are one of the largest ants in Central America.

Deterring the leafcutter ant Acromyrmex lobicornis from defoliating crops has been found to be simpler than first expected. Collecting the refuse from the nest and placing it over seedlings or around crops resulted in a deterrent effect over a period of 30 days.[5]

Species

The genus Acromyrmex contains 32 species:[1]

- Acromyrmex ambiguus Emery, 1888

- Acromyrmex ameliae De Souza, Soares & Della Lucia, 2007

- Acromyrmex aspersus F. Smith, 1858

- Acromyrmex balzani Emery, 1890

- Acromyrmex biscutatus Fabricius, 1775

- Acromyrmex coronatus Fabricius, 1804

- Acromyrmex crassispinus Forel, 1909

- Acromyrmex diasi Gonçalves, 1983

- Acromyrmex disciger Mayr, 1887

- Acromyrmex echinatior Forel, 1899

- Acromyrmex evenkul Bolton, 1995

- Acromyrmex fracticornis Forel, 1909

- Acromyrmex heyeri Forel, 1899

- Acromyrmex hispidus Santschi, 1925

- Acromyrmex hystrix Latreille, 1802

- Acromyrmex insinuator Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998

- Acromyrmex landolti Forel, 1885

- Acromyrmex laticeps Emery, 1905

- Acromyrmex lobicornis Emery, 1888

- Acromyrmex lundii Guérin-Méneville, 1838

- Acromyrmex niger F. Smith, 1858

- Acromyrmex nigrosetosus Forel, 1908

- Acromyrmex nobilis Santschi, 1939

- Acromyrmex octospinosus Reich, 1793

- Acromyrmex pubescens Emery, 1905

- Acromyrmex pulvereus Santschi, 1919

- Acromyrmex rugosus F. Smith, 1858

- Acromyrmex silvestrii Emery, 1905

- Acromyrmex striatus Roger, 1863

- Acromyrmex subterraneus Forel, 1893

- Acromyrmex versicolor Pergande, 1894

- Acromyrmex volcanus Wheeler, 1937

See also

References

- 1 2 Bolton, B. (2014). "Acromyrmex". AntCat. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- 1 2 Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press, p. 298, ISBN 0-313-33922-8.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-02. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ↑ Zhang, M. M.; Poulsen, M. & Currie, C. R. (2007), "Symbiont recognition of mutualistic bacteria by Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants", The ISME Journal, 1 (4): 313–320, doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.41.

- ↑ Ballari, S. A. & Farji-Brener, A. G. (2006), "Refuse dumps of the leaf-cutting ants as a deterrent for ant herbivory: does refuse age matter?", The Netherlands Entomological Society, 121 (3): 215–219, doi:10.1111/j.1570-8703.2006.00475.x.

External links

Media related to Acromyrmex at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acromyrmex at Wikimedia Commons