Acamprosate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral [1] |

| ATC code | N07BB03 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 11%[1] |

| Protein binding | Negligible[1] |

| Metabolism | Nil[1] |

| Biological half-life | 20 to 33 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

77337-76-9 |

| PubChem (CID) | 155434 |

| DrugBank |

DB00659 |

| ChemSpider |

136929 |

| UNII |

N4K14YGM3J |

| KEGG |

D07058 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:51042 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1201293 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

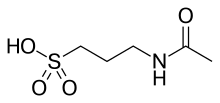

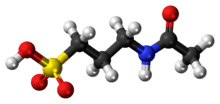

| Formula | C5H11NO4S |

| Molar mass | 181.211 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Acamprosate, sold under the brand name Campral, is a medication used along with counselling in the treatment of alcohol dependence.[2]

Acamprosate is thought to stabilize the chemical balance in the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcohol withdrawal.[3] Reports indicate that acamprosate works to best advantage in combination with psychosocial support and can help facilitate reduced consumption as well as full abstinence.[4][5] Certain serious side effects include allergic reactions, irregular heartbeats, and low or high blood pressure, while less serious side effects include headaches, insomnia, and impotence.[6] Diarrhea is the most common side-effect.[7] Acamprosate should not be taken by people with kidney problems or allergies to the drug.[8]

Until it became a generic in the United States, Campral was manufactured and marketed in the United States by Forest Laboratories, while Merck KGaA markets it outside the US. It is sold as 333 mg white and odorless tablets of acamprosate calcium, which is the equivalent of 300 mg of acamprosate.[1]

Medical uses

Acamprosate is useful when used along with counselling in the treatment of alcohol dependence.[2] Over three to twelve months it increases the number of people who do not drink at all and the number of days without alcohol.[2] It appears to work as well as naltrexone.[2]

Contraindications

Acamprosate is primarily removed by the kidneys and should not be given to people with severely impaired kidneys (creatinine clearance less than 30ml/min). A dose reduction is suggested in those with moderately impaired kidneys (creatinine clearance between 30ml/min and 50ml/min).[9][10] It is also contraindicated in those who have a strong allergic reaction to acamprosate calcium or any of its components.[9][10]

Interactions

Current studies have not shown any serious drug-drug interactions between acamprosate and alcohol, diazepam, imipramine, or disulfiram.[9] One study found that giving acamprosate with naltrexone had no harmful effects and no clinically important effects on the pharmacokinetics of either drugs.[11]

Pharmacology

The mechanism of action of acamprosate is unknown and controversial.[12] At high concentrations, well above those that occur clinically (1–3 μM), reports of inhibition of glutamate receptor-activated responses (1 mM), enhancement of NMDA receptor function (300 μM), weak antagonization of the NMDA receptor, partial agonism of the polyamine site of the NMDA receptor, and possible inhibition of the mGluR1 and mGluR5 (10 μM) have all been published.[12] However, no direct action of acamprosate at clinically-relevant concentrations has yet been reported. Moreover, a subsequent study found no action of acamprosate on the mGluR1 or mGluR5 at concentrations as high as 100 μM, nor at GABAA or glycine receptors or voltage-gated sodium channels.[12]

GABA

Ethanol and benzodiazepines act on the central nervous system by binding to the GABAA receptor, increasing the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (i.e., it is a positive allosteric modulator). In chronic alcohol abuse, one of the main mechanisms of tolerance is attributed to GABAA receptors becoming downregulated (i.e. becoming generally less sensitive to the inhibitory effect of the GABA system). When alcohol is no longer consumed, these down-regulated GABAA receptor complexes are so insensitive to GABA that the typical amount of GABA produced has little effect; compounded with the fact that GABA normally inhibits action potential formation, there are not as many receptors for GABA to bind to — meaning that sympathetic activation is unopposed, leading to sympathetic over-stimulation. Acamprosate's mechanism of action is supposed to be, at least partially, due to an enhancement effect on GABA receptors. It has been purported to open the chloride ion channel in a novel way as it does not require GABA as a cofactor, making it less liable for dependence than benzodiazepines. Acamprosate has been successfully used to control tinnitus, hyperacusis, ear pain and inner ear pressure during alcohol use due to spasms of the tensor tympani muscle.

NMDA

In addition, alcohol also inhibits the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs). Chronic alcohol consumption leads to the overproduction (upregulation) of these receptors. Thereafter, sudden alcohol abstinence causes the excessive numbers of NMDARs to be more active than normal and to contribute to the symptoms of delirium tremens and excitotoxic neuronal death.[13] Withdrawal from alcohol induces a surge in release of excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate, which activates NMDARs.[14] Acamprosate reduces this glutamate surge.[15] The drug also protects cultured cells from excitotoxicity induced by ethanol withdrawal[16] and from glutamate exposure combined with ethanol withdrawal.[17]

Calcium

In contrast to the aforementioned wide array of purported mechanisms of action, a 2013 profile animal study published in Neuropsychopharmacology[18] suggests that acamprosate has by itself no psychotropic profile, no N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor or metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 activity, and that therapeutic effects are due to the active calcium moiety co-administered with the acamprosate salt form. These findings have not yet been reproduced.

Neuroprotective effects

In addition to its apparent ability to help patients refrain from drinking, some evidence suggests that acamprosate is neuroprotective (that is, it protects neurons from damage and death caused by the effects of alcohol withdrawal, and possibly other causes of neurotoxicity).[15][19] For example, acamprosate has been found to protect cultured cells from damage induced by ischemia (inadequate blood flow).[20] The drug also protected infant hamsters from brain damage induced by injections of the toxin ibotenic acid (which exacerbates excitotoxicity, the harmful over-activation of glutamate receptors).[21]

One Brazilian study has shown that acamprosate may be an effective treatment for tinnitus.[22]

Society and culture

Names

Acamprosate is the INN and BAN. Acamprosate calcium is the USAN and JAN. It is also technically known as N-acetylhomotaurine or as calcium acetylhomotaurinate,

It is sold under the brand name Campral.

Approval

While the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States approved this drug in July 2004, it has been legal in Europe since 1989. After it approved the drug, the FDA released this statement:

While its mechanism of action is not fully understood, Campral is thought to act on the brain pathways related to alcohol abuse. Campral was demonstrated to be safe and effective by multiple placebo-controlled clinical studies involving alcohol-dependent patients who had already been withdrawn from alcohol, (i.e., detoxified). Campral proved superior to placebo in maintaining abstinence (keeping patients off alcohol consumption), as indicated by a greater percentage of acamprosate-treated subjects being assessed as continuously abstinent throughout treatment. Campral is not addicting and was generally well tolerated in clinical trials. The most common adverse events reported for patients taking Campral included headache, diarrhea, flatulence, and nausea.[23]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Campral Description" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-03-18. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 Plosker, GL (July 2015). "Acamprosate: A Review of Its Use in Alcohol Dependence.". Drugs. 75 (11): 1255–68. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0423-9. PMID 26084940.

- ↑ Williams, SH. (2005). "Medications for treating alcohol dependence". American Family Physician. 72 (9): 1775–1780. PMID 16300039.

- ↑ Mason, BJ (2001). "Treatment of alcohol-dependent outpatients with acamprosate: a clinical review.". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 Suppl 20: 42–8. PMID 11584875.

- ↑ Nutt, DJ (2014). "Doing it by numbers: A simple approach to reducing the harms of alcohol". JOURNAL OF PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY. 28: 3–7. doi:10.1177/0269881113512038. PMID 24399337.

- ↑ "Acamprosate". drugs.com. 2005-03-25. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Wilde, MI; Wagstaff, AJ (June 1997). "Acamprosate. A review of its pharmacology and clinical potential in the management of alcohol dependence after detoxification". Drugs. 53 (6): 1038–53. doi:10.2165/00003495-199753060-00008. PMID 9179530.

- ↑ "Acamprosate Oral - Who should not take this medication?". WebMD.com. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- 1 2 3 Saivin, S; Hulot, T; Chabac, S; Potgieter, A; Durbin, P; Houin, G (Nov 1998). "Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Acamprosate". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 35 (5): 331–345. doi:10.2165/00003088-199835050-00001. PMID 9839087.

- 1 2 "Campral Prescribing Information" (PDF). Forest Pharmaceuticals. 2004. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Mason, BJ; Goodman, AM; Dixon, RM; Hameed, MH; Hulot, T; Wesnes, K; Hunter, JA; Boyeson, MG (Oct 2002). "A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interaction study of acamprosate and naltrexone". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (4): 596–606. doi:10.1016/s0893-133x(02)00368-8. PMID 12377396.

- 1 2 3 Reilly, Matthew T.; Lobo, Ingrid A.; McCracken, Lindsay M.; Borghese, Cecilia M.; Gong, Diane; Horishita, Takafumi; Adron Harris, R. (2008). "Effects of Acamprosate on Neuronal Receptors and Ion Channels Expressed inXenopusOocytes". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 32 (2): 188–196. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00569.x. ISSN 0145-6008.

- ↑ Tsai, G; Coyle, JT (1998). "The role of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the pathophysiology of alcoholism". Annual Review of Medicine. 49: 173–84. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.173. PMID 9509257.

- ↑ Tsai, GE; Ragan, P; Chang, R; Chen, S; Linnoila, VM; Coyle, JT (1998). "Increased glutamatergic neurotransmission and oxidative stress after alcohol withdrawal". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (6): 726–32. PMID 9619143.

- 1 2 De Witte, P; Littleton, J; Parot, P; Koob, G (2005). "Neuroprotective and abstinence-promoting effects of acamprosate: elucidating the mechanism of action". CNS Drugs. 19 (6): 517–37. doi:10.2165/00023210-200519060-00004. PMID 15963001.

- ↑ Mayer, S; Harris, BR; Gibson, DA; Blanchard, JA; Prendergast, MA; Holley, RC; Littleton, J (2002). "Acamprosate, MK-801, and ifenprodil inhibit neurotoxicity and calcium entry induced by ethanol withdrawal in organotypic slice cultures from neonatal rat hippocampus". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 26 (10): 1468–78. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000033261.14548.D2. PMID 12394279.

- ↑ Al Qatari, M; Khan, S; Harris, B; Littleton, J (2001). "Acamprosate is neuroprotective against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity when enhanced by ethanol withdrawal in neocortical cultures of fetal rat brain". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25 (9): 1276–83. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02348.x. PMID 11584146.

- ↑ Spanagel R, Vengeliene V, Jandeleit B, Fischer WN, Grindstaff K, Zhang X, Gallop MA, Krstew EV, Lawrence AJ, Kiefer F (March 2014). "Acamprosate produces its anti-relapse effects via calcium.". Neuropsychopharmacology. 39 (4): 783–791. doi:10.1038/npp.2013.264. PMID 24081303.

- ↑ Mann K, Kiefer F, Spanagel R, Littleton J (July 2008). "Acamprosate: recent findings and future research directions". Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 32 (7): 1105–10. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00690.x. PMID 18540918.

- ↑ Engelhard, K; Werner C; Lu H; Mollenberg O; Zieglgansberger W; Kochs E (2006). "The neuroprotective effect of the glutamate antagonist acamprosate following experimental cerebral ischemia. A study with the lipid peroxidase inhibitor u-101033e". Anaesthesist. 49 (9): 816–821. PMID 11076270.

- ↑ Adde-Michel, C; Hennebert O; Laudenbach V; Marret S; Leroux P (2005). "Effect of acamprosate on neonatal excitotoxic cortical lesions in in utero alcohol-exposed hamsters". Neuroscience Letters. 374 (2): 109–112. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.037. PMID 15644274.

- ↑ Azevedo AA, Figueiredo RR (2005). "Tinnitus treatment with acamprosate: double-blind study". Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 71 (5): 618–23. doi:10.1590/S0034-72992005000500012. PMID 16612523.

- ↑ "FDA Approves New Drug for Treatment of Alcoholism". FDA Talk Paper. Food and Drug Administration. 2004-07-29. Archived from the original on 2008-01-17. Retrieved 2009-08-15.