Èrs people

The Èr people, also known as Èrsh or (in Georgian works) the Hers, are a hypothetical ancient people inhabiting northern modern Armenia, and to an extent, small areas of northeast Turkey, southern Georgia, and northwest Azerbaijan. Most of their history is constructed based on archaeological and linguistic (primarily based on placenames, with some elements) data, compared to historical trends in the region and historical writings, such as the Georgian Chronicles or the Armenian Chronicles, as well as a couple notes made by Strabo. They were a constituent of the state of Urartu, which either incorporated or conquered them during the 8th century BCE. Their relation to the main Urartians (who were probably ethnically separate from them, judging from place names) is unknown. Linguistically, based on placenames, they are thought to have been a Nakh people.

Language and culture

According to Amjad Jaimoukha, their language was a Nakh language.[1] The Urartian fortress Erebuni was named after them. According to Jaimoukha, buni is a Nakh root, meaning shelter or home, the same root which gave rise to the modern Chechen word bun (pronounced /bʊn/), meaning a cabin, or small house. Hence, Erebuni meant "the home of the Èrs". It corresponds to modern Yerevan[2] (van is a common Armenian rendering for the root bun).

According to the "Alarodian" hypothesis, which links the Nakh and other Northeast Caucasian languages with Hurrian and Urartian, and is advocated by some linguists such as Sergei Starostin, it would also be more distantly related to the language of the Ers' former rulers, the Urartians.[3] However, these theories have not gained widespread acceptance or support.

In the Georgian Chronicles, Leonti Mroveli refers to Lake Sevan as "Lake Ereta". The name of the Arax River is also attributed to the Èrs.[1] It is also called the Yeraskhi. The Armenian name is "Yeraskhadzor" (which Jaimoukha identifies as Èr + khi a Nakh water body suffix + Armenian dzor gorge).[1] Interestingly, in close proximity to the South is the "Nakhchradzor" gorge, perhaps an old home of the Dzurdzuks.[1] During the time of the kingdom of Urartu, there was a northern region near the Yerashkhadzor gorge and a little northwest of Erebuni called "Eriaki".

As part of Urartu

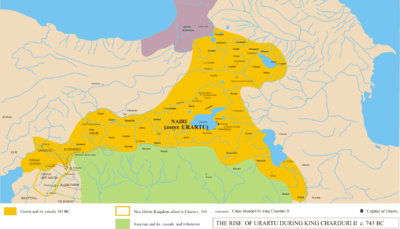

Nothing is really known about the people of Eriaki prior to their conquest or interpretation by Urartu, but the probably had lived separately before that. Urartu was originally situated around the Lake Van, but expanded in all directions, including North, probably eventually incorporating or conquering the Èrs.

Although there is a wide variety of views on the nature of the relationship, Circassian Caucasus specialist Amjad Jaimoukha asserts that

It is certain that the Nakh constituted an important component of the Hurrian-Urartian tribes in the Trans-Caucasus and played a role in the development of their influential cultures.

It has been noted that at many points, Urartu in fact extended through Kakheti into the North Caucasus:

The kingdom of Urartu, which was made up of several small states, flourished in the ninth and seventh centuries BCE, and extended into the North Caucasus at the peaks of its power...

Collapse of Urartu

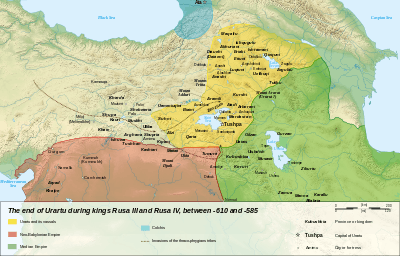

But the period of Urartian dominance was not to last in the constant power shifts in the northern Middle East region, and this had a disastrous effect on its inhabitants, as the state's power hollowed out and collapsed. As the Urartian state crumbled due to internal rotting and over-extension of territory paired with attacks by nomadic and non-nomadic invaders (including Cimmerians, the state of Assyria, the state of Taos, and the Armens), the Nakh peoples living on its Northern periphery, including the Èrs (and the Dzurdzuks, their neighbors, although they had probably fled earlier, fleeing the advance of the Medes toward the Urmia Lake near around which they lived), worried about their fate if they stayed, one by one packed up and tested fate by trying to flee and settle elsewhere, often in the mountains, where fellow Nakh peoples lived. Greek historians, such as Strabo,[6] reported the flight of "Gargareans" (root linked to gergara or kin, Chechen, the most prominent modern Nakh language) from Urartu as the state collapsed and "returning" back into the Caucasus mountains. Leonti Mroveli also stated that "many Urartians [i.e. inhabitants of Urartu], as their state collapsed, returned to the Transcauscasus, which had mostly now become a Kartlian [i.e. Kartli, the center of the Georgian Iberian state] domain".

Some authors posit that Nakh nations had a close connection of some sort to the Hurrian and Urartian civilizations in modern day Armenia and Kurdistan, largely due to linguistic similarities (Nakh shares the most roots with known Hurrian and Urartian)- either that the Nakhs were descended from Hurrian tribes, that they were Hurrians who fled north, or that they were closely related and possibly included at points in the state.[5]

The Georgian chronicles of Leonti Mroveli state that the Urartians "returned" to their homeland (i.e. Kakheti) in the Trans-Caucasus, which had become by then "Kartlian domain", after they were defeated.

Apparently, Xenophon visited Urartu in 401 BCE, and rather than finding Urartians, he only found pockets of Urartians, surrounded by Armenians.[5][7] These Urartians, as modern scholars infer, were undergoing a process of assimilation to Armenian language and culture.

See also

- Nakh peoples

- Northeast Caucasian people

- Northeast Caucasian languages

- History of Chechnya, has a section referring to the fate of the Èrs and other Urartians

- Hereti

- Balakan

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Chechens: A Handbook. Routledge Curzon: Oxon, 2005.

- ↑ See Israelyan, Margarit A (1971). Էրեբունի: Բերդ-Քաղաքի Պատմություն (Ēryebowni: Byerd-Kaghaki Patmowt'hown, Erebuni: The History of a Fortress-City) (in Armenian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Hayastan Publishing Press. pp. 8–15.

- ↑ Igor M. Diakonoff, Sergei A. Starostin. "Hurro-Urartian and East Caucasian Languages", Ancient Orient. Ethnocultural Relations. Moscow, 1988, pp. 164-207 http://starling.rinet.ru/Texts/hururt.pdf

- ↑ Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Chechens: A Handbook. p. 23

- 1 2 3 Jaimoukha. Chechens. p. 29

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, Bk. 11, Ch. 5, Sec. 1

- ↑ http://www.asor.org/pubs/nea/back-issues/ba/zimansky.html