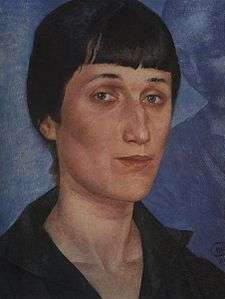

Requiem (Anna Akhmatova)

|

Requiem is an elegy written over three decades, between 1935 and 1961 by Anna Akhmatova. Akhmatova composed, worked and reworked the long sequence in secret, depicting the suffering of the common people under the Stalinist Terror.[1] She carried it with her, redrafting, as she worked and lived in towns and cities across the Soviet Union. It was conspicuously absent from her collected works, given its explicit condemnation of the purges. The work in Russian finally appeared in book form in Munich in 1963, the whole work not published within the USSR until 1987.[2][3] It would become her best known work.

The work consists of ten numbered poems that examine a series of emotional states, exploring suffering, despair, devotion, rather than a clear narrative. Biblical themes such as Christ's crucifixion and the devastation of Mary, Mother of Jesus and Mary Magdelene, reflect the ravaging of Russia, particularly witnessing the harrowing of women in the 1930s. It represented, to some degree, a rejection of her own earlier romantic work as she took on the public role as chronicler of the Terror. This is a role she holds to this day.[4] Following its publication, Requiem became known internationally for its blend of graceful language and complex and classical Russian poetry.[5]

Overview

The set of poems is introduced by one prose paragraph that briefly states how she was “picked out” to describe the months of waiting outside Leningrad Prison, along with many other women, for just a glimpse of fathers, brothers or sons who had been taken away by the secret police in Russia. Following the introductory paragraph, the core set of poems in Requiem consists of 10 short numbered poems, beginning with the first reflecting on the arrest of Akhmatova's third husband Nikolay Punin and other close confidants.[6] The next nine core poems make references to the grief and agony she faced when her son, Lev Gumilev was arrested by the secret police in 1938.[7] She writes, "one hundred million voices shout" through her "tortured mouth".

Seventeen months I've pleaded

for you to come home.

Flung myself at the hangman’s feet.

My terror, oh my son.

And I can’t understand.

Now all’s eternal confusion.

Who’s beast, and who’s man?

How long till execution?

(from Requiem. Trans. A.S. Kline, 2005)

While the first set of poems relate to her personal life, the last set of poems are left to reflect on the voices of others who suffered losses during this time of terror. With each successive poem, the central figure experiences a new stage of suffering. Mute grief, growing disbelief, rationalization, raw mourning, and steely resolve are just a few that remain constant throughout the entire cycle.[8] Writing sometimes in first person and sometimes in third person, Ahkmatova universalizes her personal pain and makes a point to connect with others who experienced the same tragedy as herself. Since the topics chosen were controversial at the time, Requiem was written in 1940 but was not published. Akhmatova believed it would be too dangerous for Requiem to be published during that period of danger and felt it was better to keep it reserved in her head, only revealing it to some of her closest friends. Following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, Akhmatova felt it was safe to share the poems she had kept secret for so long and ended up having it fully published in 1963 in Munich.[9] It was not published in Russia until 1987 due to all of the controversy that surrounded it.[9]

Structure

Requiem is separated into three sections which set the structure of the entire cycle.[9]

1. The introduction also known as the prose paragraph is located at the beginning of the cycle. It details the background story of how Anna Akhmatova came to the decision of writing this poem and also explains the environment they were a part of during that period in history. Below is the paragraph that introduces the cycle:

"During the frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I spent seventeen months waiting in prison queues in Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone "picked me out". On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me, her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear (everyone whispered there) "Could one ever describe this?" And I answered, "I can." It was then that something like a smile slid across what had previously been just a face."[5]

2. The second section of the cycle is the first ten poems after the introduction, which are references to her personal grief. Her husband Nikolay Punin had been arrested for his second time and placed into jail where he ended up passing away before he was let go.[10] In the first poem of this set titled "Dedication", she references her unsettling feelings toward his arrest and his passing away, and also reaches out to her close friends who had also been arrested. While the first paragraph is a dedication to people who were very important to her, the other nine of the second section directly relate to the arrest of her only son Lev Gumilev.[6] Akhmatova expresses her inner sadness, pain and anger about the situation her and many other women were put in. For 17 months, she waited outside the prison in Leningrad just waiting for glimpse or notification of what was going to happen to her son. This section concludes with Akhmatova describing how no one can take away the important things that go unnoticed such as a touch, a look, visits, ext.[9]

3. The third and last section of this set starts with the title "Crucifixion". This set of poems is from the perspective of the other women who also stood outside Leningrad prison waiting for just a glimpse or notification from their fathers, sons, or husbands who had been arrested also.[6] Through intricate details, she describes the grieving, pain, weakness, and fear she observed while waiting along with them during this time of terror. Overwhelmed with sadness, the ending closes with:

And let the prison dove coo in the distance

While ships sail quietly along the river.

General themes

Requiem is often said to have no clearly definable plot but has many themes which carry throughout the entire poem.[9] One of the most important themes that also stands as part of the title is the theme of "A poem without a hero".[5][9] Throughout the entire cycle and the many poems within, there is no hero that comes to the rescue. It is important for the readers to know that because it is almost always a piece that people are looking for. Akhmatova wants her readers to recognize that they had to overcome this together, not by being saved by a figment of the imagination. Also, grief, disbelief, rationalization, mourning, and resolve are just a few themes that remain constant throughout the entire cycle. These themes all connect with one another because they are all stages of suffering. Whether it be the suffering of Akhmatova herself, or the suffering of the many other women who had to face the same tragedy they all are an important part in creating the purpose for the poem. Another visible theme in the cycle is the reference to biblical people.[7] Mary Magdalene, Mary Mother of Christ, John a disciple are people who Akhmatova references.[5] It is said that she incorporates this theme into the complex cycle to reinforce the idea that although there has been a large amount of suffering amongst all of them, there is nothing left to fear. It also allows her to transcend her personal circumstances in a mythical, and supernatural way.

The last theme that seems very prominent at the end of the cycle is the idea of keeping this tragedy as a memorial. By remembering what happened and not allowing yourself to ever forget is a part of the stage of suffering that allows you to move on in life. This again ties back into the stages of suffering, so it is all interconnected.

Critical reception

Akhmatova feared that it would be too dangerous for herself and those around her if she released the poem during the 1940s when it was written. It wasn't until after the death of Stalin in 1953 that she finally decided that it was the right time to have it published. Although she was not celebrated by the Soviet leadership, she was tolerated and by 1987 the whole cycle of Requiem was finally published in the USSR.[2] After finally being published, Akhmatova's critics labelled Requiem as a blend of graceful language and complex classical Russian forms of poetry.[7]

Other works

Along with Requiem, Akhmatova had many other works that put her on the map as being known as one of the best poets in Russia. Before writing Requiem, she was mostly known for her short lyrical poems.[5]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ivan Turgenev. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Requiem (Anna Akhmatova) |

References

- ↑ Who's Who in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. 1999.

- 1 2 Martin, R. Eden (April 2007). "Collecting Anna Akhmatova" (PDF). Caxtonian. Caxton Club. XV (4): 12—16.

- ↑ Harrington, Alexandra (2006). The poetry of Anna Akhmatova: living in different mirrors. Anthem Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84331-222-2.

- ↑ Wells, David (1996). Anna Akhmatova: Her Poetry. Berg Publishers. pp. 70—74. ISBN 978-1-85973-099-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Requiem". Poem Hunter. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- 1 2 3 "Anna Akhmatova". UMV. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- 1 2 3 "Political Cultures in Poetry". Poems for Human Rights. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ↑ Gorenko, Anna. "Requiem". Enotes. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Liukkonen, Petri. "Anna Akhmatova". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "An Elegy for Russia: Anna Akhmatova's Requiem". JSTOR 309548.